Home » Criminology (Page 16)

Category Archives: Criminology

Brought to You by Tampax

Whilst social media platform Twitter is routinely criticised for being a toxic cesspit of trolls, racism and discrimination, there is an opposing story: commentators like Kelechi have used their platforms to mock power. To the untrained eye, her tweet appears random but it is actually referencing #TamponGate – a scandal that was picked up by the British press in 1993 when Charles confessed to Camilla he wanted to “live inside” her trousers, joking that he might be reincarnated in the life after death as tampon.

Discourses to tampons aside, potential of solidarity and coalition in our shared trauma under the British Crown will be manifestly apparant this bank holiday weekend – just as it was during the scenes on social media during the Commonwealth Games, Jubilee and Queen’s Funeral. Black Twitter, Irish Twitter, and Indian Twitter alongside Scouser Twitter and Celtic Fans Twitter will probably be linking up. Edutainment and memes aplenty. With the long bank holiday weekend, I know other political commentators will take to Twitter, Instagram, TikTok and Tumblr to vent their frustrations.

Potential for coalition and solidarity presents itself in the deep space of the interweb. Under the thinking of the social media posts, there sits an exhaustion from groups that have long been exploited by the monarchy. Audre Lorde (1984) once termed racism and sexism as “grown up words” (p152) revisiting how victims often acquire the language to articulate their experience after the experience. In her blog post ‘Feminism and Fragility’, sociologist Sara Ahmed (2016) further states “Once we have the words, you are putting a sponge to the past: mopping things up, all that spillage.” So, this experience revisits the bit bitting at institutional violence and how actions become institutionalised by repeated behaviours.

As Bob Marley said

“So if you are the big tree

Small Axe, (Burnin’, 1973)

We are the small axe

Ready to cut you down (well sharp)

To cut you down”

Meanwhile, I must ask ‘did Tesco actually call [redacted] a [redacted]?

Whilst the pomp of the coronation is absorbed into the brains of millions of people around the world, this is happening during a Cost of Capitalism crisis, paid for at the taxpayers’ expense. Sounds of abolish the monarchy can be heard around the world. I do wonder what Britain would like without this mafia institution. When you do start looking at these systems more closely, you begin to see how entangled the monarchy is with other institutions – police, prisons, and many more – including entities like Honours committees, the privy council and House of Lords too. To abolish the monarchy is also linked with other abolitionist narratives.

Like every other criminology blog entry, now let’s discuss Guy DeBord’s theory of ‘the spectacle’. ‘The spectacle’, said French Marxist Guy DeBord, is a system of domination that claims your attention and then your attention faciliates your subjugation. So, the irony is that even with my dislike of the monarchy – I’m doomed if I do, and doomed if I don’t talk about it – because within the advertised life of the spectacle, there’s nothing I can say that doesn’t make the spectacle stronger.

Meanwhile, the appeal of Harry & Meghan in this case act as a violent juxtaposition to a British public who in many ways still see “good” and “bad” royalty, not The Crown as a wholly imperialistic violent construct. To me things like coronations, jubilees keep us distracted. Even when trying to avoid such nonsense, our world has become so saturated by media. As Guy DeBord writes “There is no place left where people can discuss the realities which concern them, because they can never lastingly free themselves from the crushing presence of media discourse and the various forces organised to relay it” (DeBord, 1998: 19).

Anyhow, now as all of us are immersed in the spectacle, we may as well stay implicated. In the 1960s, it was possible to think critically. Now, being a philisopher just means you have watched Inception!

Rise of the machines: fall of humankind

May is a pretty important month for me: Birthdays, graduations, what feels like a thousand Bank Holidays, marking deadlines, end of Semester 2 and potentially some annual leave (if I haven’t crashed and crumbled beforehand). And all of the above is impacted by, or reliant on the use of machines. Their programming, technology, assistance, and even hindrance will all have a large impact on my month of May and what I am finding, increasingly so, is that the reliance on the machines for pretty much everything in relation to my list above is making my quite anxious for the days to come…

Employment, education, shopping, leisure activities are all reliant on trusty ol’ machines and technology (which fuels the machines). The CRI1003 cohort can vouch, when I claim that machines and technology, in relation to higher education, can be quite frustrating. Systems not working, or going slow, connecting and disconnecting, machines which need updates to process the technology. They are also fabulous: online submissions, lecture slides shown across the entirety of the room not just one teeny tiny screen, remote working, access to hundreds of online sources, videos, typing, all sorts! I think the convoluted point I am trying to get too is that the rise of the reliance on machines and technology has taken humankind by storm, and it has come with some frustrations and some moments of bliss and appreciation. But unfortunately the moments of frustration have become somewhat etched onto the souls of humankind… will my laptop connect? Will my phone connect to the internet? Will my e-tickets download properly? Will my banking app load?

Why am I pondering about this now?

I am quite ‘old school’ in relation to somethings. I am holding on strong to paper books (despite the glowing recommendations from friends on Kindles and E-readers), I use cash pretty much all the time (unless it is not accepted in which case it is a VERY RARE occasion that the business will receive my custom), and I refuse to purchase a new phone or update the current coal fuelled device I use (not literally but trying to be creative). Why am I so committed to refusing to be swept along in the rise of the machines? Simple: I don’t trust them.

I have raised views about using card/contactless to purchase goods elsewhere and I fully appreciate I am in a minority when it comes to the reliance on cash. However, what happens when the card reader fails? What happens when the machine needs an update which will take 40mins and the back up machine also requires an update? Do traders and businesses just stop? What happens when the connection is weak, or the connection fails? What happens when my e-tickets don’t load or my reservation which went through on my end, didn’t actually go through on their end? See, if I had spoken to someone and got their name and confirmed the reservation, or had the physical tickets, or the cash: then I would be ok. The reliance on machines removes the human touch. And often adds an element of confusion when things go wrong: human error we can explain, but machine error? Harder to explain unless you’re in the know.

May should be a month of celebrations and joy: Birthdays, graduations, end of the Semester, for some students the end of their studies. But all of this hinders of machines. Yes, it requires humans to organise and use the technology but very little of it is actually reliant on humans themselves. I am oversimplifying. But I am also anxious. Anxious that a number of things we enjoy, rely on and require for daily life is becoming more and more machine-like by the day. I have an issue, can I talk to a human- nope! Talk to a bot first then see if a human is needed. So much of our lives are becoming reliant on machines and I’m concerned it means more will go wrong…

Sometimes it is very hard to find the words

This week our learning community lost one of our members; Kwabena Osei-Poku (known to his nearest and dearest as Alfred) who was killed on Sunday 23 April 2023. At such times, it is very difficult to find the right words, but to say nothing, would do a grave disservice.

The Thoughts from the Criminology Team would like to express our deepest condolences to the family, friends, and communities for whom Kwabena Osei-Poku (Alfred) was such an important person. We wish you time, space and peace to come together to mourn your terrible loss.

The Moral Dilemma of Using Artificial Intelligence

Background

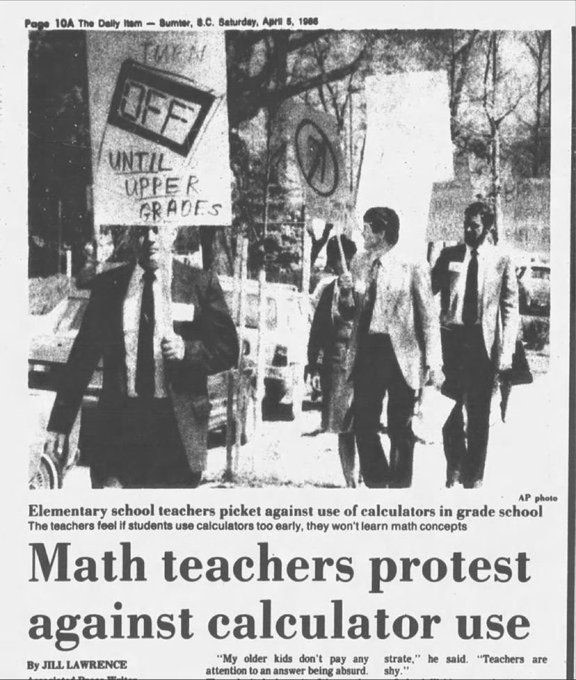

Many academics, students, and industry practitioners alike are currently faced with the moral dilemma of whether to use or apply artificial intelligence (AI) to different aspects of their work and assessments. However, this is not the first-time humans are faced with such a moral dilemma, particularly in academia. Between 2003 and 2005 when I wrote at least 3 entrance examinations administered by the Joint Admission Matriculation Board Examination for university admission seekers in Nigeria, the use of electronic or scientific calculators were prohibited. Few years afterwards, the same exam board that prohibited my generation from using calculators for our accounting and mathematics exams started providing the same scientific calculators to students registered for the same exam. Understandably, AI is significantly different from scientific calculators, but similar rhetoric and condemnation resulted from the introduction of calculators in schools, same as the emergence of Google with its search capabilities.

For the most part, ChatGPT, the free OpenAi model publicly released in November 2022 drew public attention to the use and capability of AI and is often considered as the breakthrough of AI. However, prior to this, humans have long embraced and used certain aspects of AI to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making. Many academics not only use reference managers, but also encourage students to do so. We also use and teach students how to use the numerous computer-aided data analysis software for statistical and qualitative data analysis given the potential and capability of these software to replicate tasks that would ordinarily take us longer to accomplish. These are but few examples of some of the AI tools we use, while many others exist.

Types and examples of AI

There are several types of AI, including machine learning, natural language processing, expert systems, robotics, and computer vision. Machine learning is the commonly used type of AI. It involves training algorithms to learn from data and improve their performance over time, typical examples include Google Bard which performs similar tasks as ChatGPT. Natural language processing allows machines to understand and interpret human language, while expert systems are designed to replicate the decision-making capabilities of human experts. Robotics involves the development of machines that can perform physical tasks, and computer vision focuses on enabling machines to interpret and analyse visual information. Other common examples of AI include virtual personal assistants like Siri and Alexa, self-driving cars, and facial recognition software. With the wide array of AI tools, it is obvious that AI can be applied in different fields of human endeavour.

Application of AI

AI is currently being used in various institutions of society, including healthcare, finance, education, transportation, and the military. In healthcare, AI is being used to develop personalized treatment plans, predict disease outbreaks, improve medical image analysis, and carebots consultations is a near possibility. In finance, AI is being used for fraud detection, risk management, and algorithmic trading. In transportation, self-driving cars and drones are being developed and currently tested using AI, while in the military, AI is being used for autonomous weapons systems and intelligence gathering. In education, AI is being used for personalized learning, student assessment, referencing, and teacher training through the help of numerous AI tools. I recently responded to reviewer feedback on a book chapter and in doing so, I noticed my reference list which was not spotted by my reviewers was not appropriately aligned with the examples provided from the publisher. It would take me 2 hours to format the list despite already having the complete information of sources I cited. Interestingly, I did not spend half of this time on the reference list of my doctoral thesis because I used a reference manager.

Benefits of AI

Clearly, AI has many potential benefits. It has the potential to improve efficiency and accuracy in various industries, leading to cost savings and improved outcomes. AI can also provide personalized experiences for users, such as in the case of virtual assistants and personalized learning platforms. More so, where properly applied, it would not only improve productivity and save time, but result in increased efficiency. Researchers would appreciate the ability to make sense of bulky data using clicks and programmed controls in graphical, visual, or even coded formats. In healthcare, AI can improve diagnosis and treatment, leading to better patient outcomes. In addition, AI can be used for environmental monitoring and conservation efforts. The benefits from the use and application of AI across human endeavours are legion and I would be understating the significance if I attempt to elaborate further.

Shortcomings of AI, Concerns, and Reactions

Nonetheless, AI evokes certain concerns. New York City education department reportedly blocked ChatGPT on school devices and networks, and in respond to a tweet on this, Elon Musk replied, ‘it’s a new world. Goodbye homework.’ Musk’s reply reflects the array of reactions and responses emanating from the understanding of society with the capability of AI tools. And without a doubt, machine learning AI tools such as ChatGPT and Google Bard can be used to generate essay contents, likewise content for academic work. I imagine students have already began taking advantage of the capabilities of these tools, including others capable of summarising articles. Some Tweeps who regularly tweet about the capability and how to use AI tools have experienced astronomical growth in the number of their followers and engagement with such tweets over the past few months.

Without a doubt, academics have reasons to be concerned, particularly because AI undermines learning and scholarship by offering easy alternatives to reading, learning, and engaging with course materials. Students could generate essays with AI and gain unfair advantage over non-users and although the machine learning models do generate false, bias, and discriminatory results, they could over time generate the capability to overcome these. Claims have also been made that automation using AI has the potential to result in job losses for academics and other professionals, but beyond this, concerns over data safety and regulation are rife.

AI Regulation

Some tech leaders including Elon Musk recently signed a statement urging that further development of AI beyond the capability of ChatGPT 4 should be halted until adequate regulations are put in place as it portends profound risks to society. The Turnitin plagiarism software provider which acclaims itself as ‘the leading provider of academic integrity solutions’ introduced and integrated the Turnitin’s AI writing detection tool for their service users. Universities and other users may likely adopt this to discourage students from using AI for assessments. However, the practicability of this enforcement is still challenging as issues around real-world false-positive report rates have been observed. An alternative approach adopted by some publishers including Taylor & Francis, Sage, and Elsevier is that authors declare the use of AI in their work with justification. Italy recently blocked ChatGPT over privacy concerns prompting the significance of AI regulation.

Conclusion

AI has the potential to improve efficiency and accuracy in various industries, leading to cost savings and improved outcomes, however, it is important to be aware of the potential risks associated with the technology. While AI has significant benefits, such as improved efficiency and accuracy, it also has drawbacks that must be considered. Academics must find ways to balance the benefits and drawbacks of AI to ensure that learning and scholarship are not undermined. It is important to recognize that AI is not a substitute for reading, learning, and engaging with course materials, and it should be used as a tool to augment human intelligence rather than replace it. Equally, it is also important to ensure that AI is used in a responsible and ethical manner. By carefully considering the pros and cons of AI, we can ensure that it is used to its full potential while minimizing the risks.

PS. Some parts of this blog were edited/generated by AI.

“My Favourite Things”: Paul

My favourite TV show - I prefer a movie any day.. episodes are draining

My favourite place to go - Home

My favourite city - London, Zanzibar, and Lagos... Ain’t no party like a Lagos party!

My favourite thing to do in my free time - Bonding with my toddler

My favourite athlete/sports personality - – BOXING: The Special One! Kell Brook

My favourite actor - Joe Pesci

My favourite author - Sidney Sheldon

My favourite drink - Depends.. Red wine after work or Whiskey for the Weekends

My favourite food - Medium Rare Steak, Lasagne (only from Rodizio Rico, O2 arena), or Egusi & Pounded Yam (Authentic)

My favourite place to eat - As long as the wine is delightful and the food is delicious, I don’t mind

I like people who - are generous & helpful

I don’t like it when people - don’t mind their business

My favourite book - The Doomsday Conspiracy

My favourite book character - Who has time to read fiction?

My favourite film - The Goodfellas, of course!

My favourite poem - 'The Second Coming' by William B Yeats

My favourite artist/band - FELA!

My favourite song - 1. Coffin for Head of State by Fela

2. The soundtrack of the Sound of Music – that’s one album I can listen to without skipping a track (My wife thinks I’m weird)

My favourite art - Jean Basquiat: GOD, LAW – an exceptional piece full of symbolism. I need to write a blog on this painting at some point!

My favourite person from history - My favourite person from history – Too many to name just one – but for the sake of this blog, I’ll go with Patrice Lumumba of the Democratic Republic of Congo

Is Easter relevant?

What if I was to ask you what images will you conjure regarding Easter? For many pictures of yellow chicks, ducklings, bunnies, and colourful eggs! This sounds like a celebration of the rebirth of nature, nothing too religious. As for the hot cross buns, these come to our local stores across the year. The calendar marks it as a spring break without any significant reference to the religion that underpins the origin of the holiday. Easter is a moving celebration that observers the lunar calendar like other religious festivals dictated by the equinox of spring and the first full moon. It replaces previous Greco-Roman holidays, and it takes its influence for the Hebrew Passover. For those who regard themselves as Christians, the message Easter encapsulates is part of their pillars of faith. The main message is that Jesus, the son of God, was arrested for sedition and blasphemy, went through two types of trials representing two different forms of justice; a secular and a religious court which found him guilty. He was convicted of all charges, sentenced to death, and executed the day after sentencing. This was exceptional speed for a justice system that many countries will envy. By all accounts, this man who claimed to be king and divine became a convicted felon put to death for his crimes. The Christian message focuses primarily on what happened next. Allegedly the body of the dead man is placed in a sealed grave only to be resurrected (return from the death, body and spirit) roamed the earth for about 40 days until he ascended into heavens with the promise to be back in the second coming. Christian scholars have been spending time and hours discussing the representation of this miracle. The central core of Christianity is the victory of life over death. The official line is quite remarkable and provided Christians with an opportunity to admire their head of their church.

What if this was not really the most important message in the story? What if the focus was not on the resurrection but on human suffering. The night before his arrest Jesus, according to the New Testament will ask “Father, if thou be willing, remove this cup from me” in a last attempt to avoid the humiliation and torture that was to come. In Criminology, we recognise in people’s actions free will, and as such, in a momentary lapse of judgment, this man will seek to avoid what is to come. The forthcoming arrest after being identified with a kiss (most unique line-up in history) will be followed by torture. This form of judicial torture is described in grim detail in the scriptures and provides a contrast to the triumph of the end with the resurrection. Theologically, this makes good sense, but it does not relate to the collective human experience. Legal systems across time have been used to judge and to punish people according to their deeds. Human suffering in punishment seems to be centred on bringing back balance to the harm incurred by the crime committed. Then there are those who serve as an example of those who take the punishment, not because they accept their actions are wrong, but because their convictions are those that rise above the legal frameworks of their time. When Socrates was condemned to death, his students came to rescue him, but he insisted on ingesting the poison. His action was not of the crime but of the nature of the society he envisaged. When Jesus is met with the guard in the garden of Gethsemane, he could have left in the dark of the night, but he stays on. These criminals challenge the orthodoxy of legal rights and, most importantly, our perception that all crimes are bad, and criminals deserve punishment.

Bunnies are nice and for some even cuddly creatures, eggs can be colourful and delicious, especially if made of chocolate, but they do not contain that most important criminological message of the day. Convictions and principles for those who have them, may bring them to clash with authorities, they may even be regarded as criminals but every now and then they set some new standards of where we wish to travel in our human journey. So, to answer my own question, religiosity and different faiths come and go, but values remain to remind us that we have more in common than in opposition.

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic

This week a book was released which I both co-edited and contributed to and which has been two years in the making. When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is a volume combining a range of accounts from artists to poets, practitioners to academics. Our initial aim of the book was borne out of a need for commemoration but we cannot begin to address this without considering inequalities throughout the pandemic.

Each of the four editors had both personal and professional reasons for starting the project. I – like many – was (and still is) deeply affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. When we first went into lockdown, we were shown the data every day, telling us the numbers of people who had the virus and of those who had died with COVID-19. Behind these numbers, I saw each and every person. I thought about their loved ones left behind, how many of them died alone without being able to say goodbye other than through a video screen. I thought about what happened to the bodies afterwards, how death rites would be impacted and how the bereaved would cope without hugs and face to face social support. Then my grandmother died. She had overcome COVID-19 in the way that she was testing negative. But I heard her lungs on the day she died. I know. And so, I became even more consumed with questions of the COVID-19 dead, with/of debates. I was angry at the narratives surrounding the disposability of people’s lives, at people telling me ‘she had a good innings’. It was personal now.

I now understood the impact of not being able to hug my grandpa at my grandmother’s funeral, and how ‘normal’ cultural practices surrounding death were disturbed. My grandmother loved singing in choirs and one of the traumatic parts of our bereavement was not being able to sing at her funeral as she would have wanted and how we wanted to remember her. Lucy Easthope, a disaster planner and one of my co-authors speaks of her frustrations in this regard:

“we’ve done something incredibly traumatising to the families that is potentially bigger than the bereavement itself. In any disaster you should still allow people to see the dead. It is a gross inhumanity of bad planning that people couldn’t’t visit the sick, view the deceased’s bodies, or attend funerals. Had we had a more liberal PPE stockpile we could have done this. PPE is about accessing your loved ones and dead ones, it is not just about medical professionals.”

The book is divided into five parts, each addressing a different theme all of which I argue are relevant to criminologists and each part including personal, professional, and artistic reflections of the themes. Part 1 considered racialised, classed, and gendered identities which impacted on inequality throughout the pandemic, asking if we really are in this together? In this section former children’s laureate Michael Rosen draws from his experience of having COVID-19 and being hospitalised in intensive care for 48 days. He writes about disposability and eugenics-style narratives of herd immunity, highlighting the contrast between such discourse and the way he was treated in the NHS: with great care and like any other patient.

The second part of the book considers how already existing inequalities have been intensified throughout the pandemic in policing, law and immigration. Our very own @paulsquaredd contributed a chapter on the policing of protests during the pandemic, drawing on race in the Black Lives Matter protests and gender in relation to Sarah Everard. As my colleagues and students might expect, I wrote about the treatment of asylum seekers during the initial lockdown periods with a focus on the shift from secure and safe self-contained housing to accommodating people seeking safety in hotels.

Part three considers what happens to the dead in a pandemic and draws heavily on the experiences of crematoria and funerary workers and how they cared for the dead in such difficult circumstances. This part of the book sheds light on some of the forgotten essential workers during the pandemic. During lockdown, we clapped for NHS workers, empathised with supermarket workers and applauded other visible workers but there were many less visible people doing valuable unseen work such as caring for the dead. When it comes to death society often thinks of those who cared for them when they were alive and the bereaved who were left to the exclusion of those who look after the body. The section provides some insight into these experiences.

Moving through the journey of life and death in a pandemic, the fourth section focusses on questions of commemoration, a process which is both personal and political. At the heart of commemorating the COVID-19 dead in the UK is the National COVID Memorial Wall, situated facing parliament and sat below St Thomas’ hospital. In a poignant and political physical space, the unofficial wall cared for by bereaved family members such as Fran Hall recognises and remembers the COVID dead. If you haven’t visited the wall yet, there will be a candlelit vigil walk next Wednesday, 29th March at 7pm and those readers who live further afield can digitally walk the wall here, listening to the stories of bereaved family members as you navigate the 150,837 painted hearts.

The final part of the book both reflects on the mistakes made and looks forward to what comes next. Can we do better in the next pandemic? Emergency planner Matt Hogan presents a critical view on the handling of the pandemic, returning to the refrain, ‘emergency planning is dead. Long live emergency planning’. Lucy Easthope is equally critical, developing what she has discussed in her book When the Dust Settles to consider how and what lessons we can learn from the management of the pandemic. Lucy calls out for activism, concluding with calls to ‘Give them hell’ and ‘to shout a little louder’.

Concluding in his afterword, Gary Younge suggests this is ‘teachable moment’, but will we learn?

When This is Over: Reflections on an Unequal Pandemic is published by Policy Press, an imprint of Bristol University Press. The book can be purchased directly from the publisher who offer a 25% discount when subscribing. It can also be purchased from all good book shops and Amazon.

An inspirational note to students on the issue of students’ non-engagement in Universities

I am not a motivational speaker, nor claim to have been inducted into the motivational speaker’s hall of fame. However, my choice to write about this blog stems from some of the challenges being faced by students that I have observed in the last couple of months. This is an inspirational blog for students and not so much about the issues of laziness in studies and so on. The aim here is to try to guide students on how they can fight through some of the challenges they are going through and be better achievers. As an educator, I owe it a duty to myself to offer advice and guidance to my students wherever necessary – in the hope that they can benefit sufficiently from the experiences that university life brings them. Remember my first point, I am not a motivational speaker, and so the recommendations that I present here are not exhaustive but brief and straight to the point.

In this post-pandemic era, several academics have drawn attention to the general lack of engagement of students in their various universities, and some colleagues have written and spoken about this issue on different platforms and forums. Some academics and students, none I know, often conclude and sum up the problem as ‘mere laziness’. While I do not disagree entirely with them in some cases, I wish to reflect on some of my observations with students from different universities. In these dialogues, my aim was to know their views on the general lack of engagement with their studies and to pick their brains on why some students struggle to attend classes. Many issues have been raised, but I will attempt to sum them up into three categories.

Firstly, one of the key issues that some students have raised is the impact of the pandemic and the need to bring back remote learning. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 messed us all up, and I get it. It was a painful period of uncertainty and a period where academic achievements dropped almost to their lowest across many countries. Online collaborate, and other online classes made life really easy for many students to the point where students could turn up to their 9 am online class under their duvet just a few minutes before the start of the class. The obligation to complete workshop reading was minimal because students could easily fake a network connection glitch and sign out when called to answer a question. There was also no obligation (in some cases) to turn on your camera or mic – because the famous phrase ‘my mic isn’t working’ was not too far away. These examples may seem inconsequential, but they help us understand some foundational problems affecting students’ motivation to engage with their studies.

We should also not forget that the need to queue up for trains at 7 am, where you have people breathing down your neck during the expensive peak time or rush hour period to meet a 9 am lecture, was reduced to the lockdown rules. This life has led to what I call the ‘soft life’. The soft life of having things done at your own time, in your bed, and at your own pace. To a large extent, the ‘soft life’ of remote learning has made it really difficult for some students to readjust to real life and to fire up their motivations to engage with their studies. My recommendation is that students start fighting through this soft life because the real-life upon graduation is not particularly soft, and the labour market (as some of you may be aware) is particularly fierce in its competition.

The second issue here is the problem of finance and the current cost-of-living crisis. I will not go into specific details because we are all feeling the heat of the current austerity, but the result of the current cost of living crises, such as the rise in transportation fares, has been raised as one of the reasons why students do not turn up to classes. We all know that the austere situation of price hikes is being experienced by many of us today. As a result, we are witnessing several strike actions across the country. From teachers to train drivers and from hospital workers to bus drivers, hundreds of thousands of workers are calling for changes in their pay schemes, working conditions and so on. Students are also suffering from these crises too, and it becomes even more compounded for students with dependents.

We can all agree that studying under harsh financial conditions can increase anxiety and reduce motivation to engage in university. These, coupled with family commitments and health challenges, are a recipe for discouragement and demoralisation. In managing this problem in academic studies, one of the key recommendations is for students to identify the support services available to them in their various institutions. Get in touch with your lecturers and update them on your predicament. Don’t ‘ghost’ on your PATs; speak to your academic advisers and other services available to you as you deem fit. Keeping your problems to yourself will only intensify anxiety. After all, a problem well stated is a problem half solved.

Another overarching narrative in my dialogue with some students reflects the general feeling of not wanting to go to university because of a lack of belonging to the campus or the course/module. Some students have noted higher confidence levels in peer learning and that their inability to establish a strong relationship with friends on campus or in classrooms has made it difficult for them to engage. When it relates to in-class workshop exercises, minimal students attend class, thus restricting peer learning. I once heard, ‘why do I need to attend when it’s only going to be 3 of us in the class’. Again, very many examples have been raised in my dialogues, but what is important here is for students to recognise some of the benefits of this and to use it to their advantage instead of taking it as a reason not to engage. One example is that such situations can provide a more ‘personable atmosphere’ where you can clarify burning issues relating to the module. It can also help with attention, and it can help build confidence.

Gnerally, non-engagement with studies has some implications for later years. Gone were the days when the probability of getting a job was relatively high upon completing university degree. However, in recent times, the competition in the labour market has become so stiff that those with a 2.1 or 1st-class degree sometimes find it hard to secure a job – particularly where experience is limited. Making informed decisions, being autonomous in your education and taking responsibility for your education will assist in dealing with quite a lot of challenges in later years. Remember the saying, if life throws lemons at you, make lemonade out of it. So keep on striving.

Overall, anxiety, stress and demoralisation reduce work productivity and social functioning. We are in a period where we, as a society, need each other more than ever. People are struggling and going through different crises, and as a people, the least we can do is to be kind to individuals and alley their fears whenever possible and necessary. Kindness here becomes the goal.

I hope you find strength for those going through other issues, such as ill health and other challenges that are beyond their control! Happy Weekend!

Thinking about ‘Thoughts from the Criminology Team’

This is the sixth anniversary of the blog, and I am proud to have been a contributor since its inception. Although, initially I only somewhat reluctantly agreed to contribute. I dislike social media with a passion, something to be avoided at all costs, and I saw this as yet more intrusive social media. A dinosaur, perhaps, but one that has years of experience in the art of self-preservation. Open up to the world and you risk ridicule and all sorts of backlash and yet, the blog somehow felt and feels different. It is not a university blog, it is our team;s blog, it belongs to us and the contributors. What is written are our own personal opinions and observations, it is not edited, save for the usual grammar and spelling faux pas, it is not restricted in any way save that there is an inherent intolerance within the team for anything that may cause offence or hurt. Government, management, organisations, structures, and processes are fair game for criticism or indeed ridicule, including at times our own organisation. And our own organisation deserves some credit for not attempting to censure our points of view. Attempts at bringing the blog into the university fold have been strongly resisted and for good reason, it is our blog, it does not belong to an institution.

As contributors, and there are many, students, academics and guests, we have all been able to write about topics that matter to us. The blog it seems to me serves no one purpose other than to allow people space to write and to air their views in a safe environment. For me it serves as a cathartic release. A chance to tell the world (well at least those that read the blog) my views on diverse topics, not just my views but my feelings, there is something of me that goes into most of my writing. It gives me an opportunity to have fun as well, to play with words, to poke fun without being too obvious. It has allowed us all to pursue issues around social injustices, to question the country, indeed the world in which we live. And it has allowed writers to provide us all with an insight into what goes on elsewhere in the world, a departure from a western colonial viewpoint. I think, as blogs go it is a pretty good blog or collection of blogs, I’m not sure of the terminology but it is certainly better than being a twit on Twitter.

Cash Strapped, Vote-Buying, Petroleum Scarcity, and the Challenge of a 21st Century Election

Democratic elections are considered an important mechanism and a powerful tool used to choose political leaders. However, the level of transparency and the safety of votes, the electorates, and the aspirants as recent elections in supposed strong democracies indicate is not a given. Even more, in weak and fragile states, voters grapple with uncertainties including the herculean task of deciding on whom or perhaps what to pledge allegiance to?

Nigerians face such uncertainties as over 93 million voters are set to decide the new leadership of the most populous country in Africa in less than 24 hours. Three contestants: Ahmed Bola Tinubu of the ruling All Progressive Congress (APC); Peter Obi of the Labour Party(LP); and Atiku Abubakar of the Peoples Democratic Party (PSP) are considered the major contestants of the coveted seat of the presidency. All 3 contestants are neither strangers to political power nor free of controversies. Nevertheless, a plethora of problems awaits the successful candidate, including a spiking impatience with government policies from the populace.

Since assuming office in 2015, President Muhammadu Buhari has consciously implemented numerous policies aimed at changing the tide of the crippling economy of Nigeria. One of this was tightening control of foreign exchange and forex restrictions to minimise pressure on the weak exchange rate of the naira against other currencies, and to encourage local manufacturing. Furtherance to this, the government implemented more restrictions including closing all its land borders in August 2019 to curtail smuggling contrabands and to boost agricultural outputs. These policies have been criticised for increasing the hardship of the mostly poor masses and failing to yield desired goals, despite its resulting in an increase in local production of some agricultural products.

The aviation sector and multinational companies were also heavily impacted by the forex restrictions. International airliners were unable to access and repatriate their business funds and profits. As a result, some suspended operations while some multinationals closed down completely. Flawed policy articulation and implementation and a slow or total failure to respond to public disenchantment has been the bane of the 8 years of Buhari regime which ends in a few months. While the masses grappled with surviving movement restrictions during the Covid-19 lockdown, palliative meant for to ease their suffering were hoarded for longer than necessary, thereby provoking series of mass looting and destruction of the storage warehouses.

Demands for action and accountability over police reform also assumed a painful dimension. On 20 October 2020, peaceful protesters demanding the abolishment of a notoriously corrupt, brutal, rogue, and stubborn police unit called SARS were attacked by government forces who killed at least 12 protesters. Incidents as this supports Nigeria’s ranking as an authoritarian regime on the democratic index. Unsurprisingly, the regime appears numb to the spate of violence, insecurity, and recurring killings perpetrated by a complex mix of militias, criminal groups, terrorists, and state institutions as the #EndSARS massacre demonstrates. Thus, a wave of migration among mainly skilled and talented young Nigerians now manifests as a #Japa phenomenon. The two most impacted sectors, health and education ironically supply significant professionals in nations where the political class seek medical treatment or educate their children while neglecting own sectors.

Certainly, the legacy of the Buhari regime would be marred by these challenges which his party presidential candidate and prominent party stalwarts have distanced from. Indeed, they fear electorates would vote against the party as a protest over their suffering. Suffice it that Nigerians lived through the previous year in acute scarcity and non-availability of petroleum products, which further deepened inflation. Currently, cash scarcity is causing untold hardship due to the implementation of a currency redesign and withdrawal limits policy. The timing of the implementation of the policy coincides with the election and is thought to aim at curtailing vote-buying as witnessed in party primary elections. However, there is no guarantee that bank officials would effectively implement the policy.

Thus, as Nigeria decides, the 3 contestants present different realities for the country. For some, voting in the ruling APC candidate who has a questionable history could mean a continuation of the woes endured during the Buhari regime. The PDP candidate who was instrumental in the 2015 election of Buhari has severally been fingered for numerous controversies and corruption, despite having not been prosecuted for any. Similarly, allegations levelled against the LP candidate who has found wide popularity and acceptance amongst the young population has not resulted in any prosecution. However, while the candidate is popular for his anti-establishment stance and desire to change the current system, it is unclear if his party which has no strong political structure, serving governors, or representatives can pull the miracle his campaign has become associated with to win the coveted seat.