Home » Criminology (Page 12)

Category Archives: Criminology

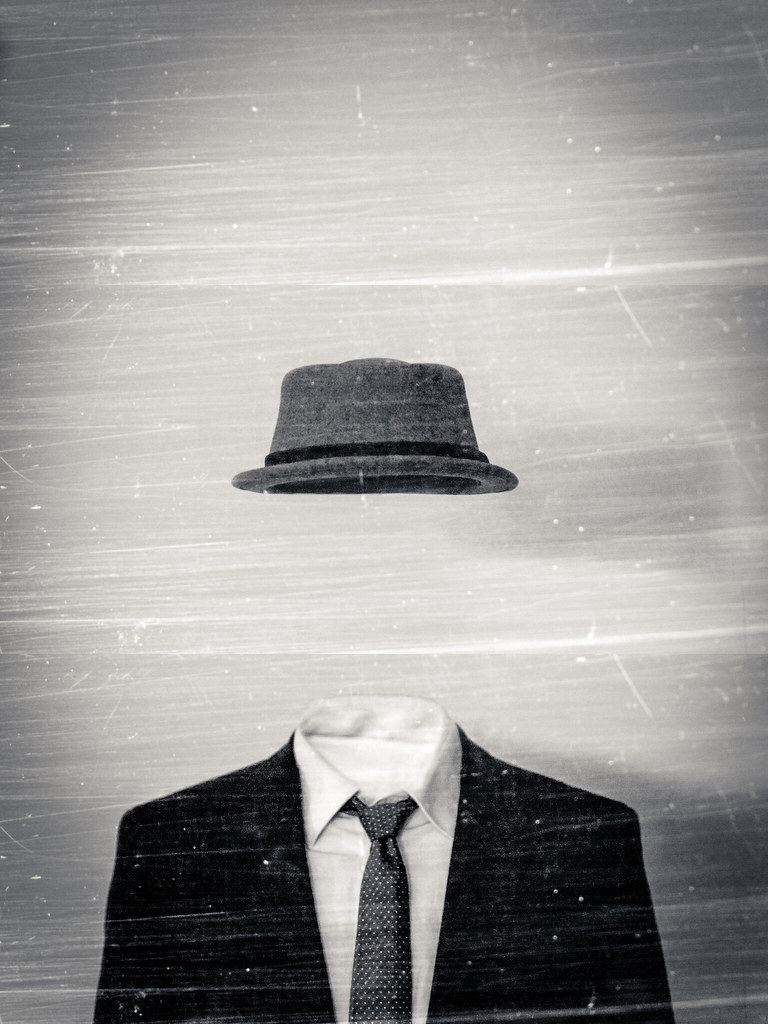

It’s all about me: when did I become invisible?

I wander around on the pavement, earbuds neatly fitted, mobile phone conveniently held in front of me so I can see the person I’m talking to. You can all listen to my conversation whilst attempting to navigate around me, oops, someone bumped into me, a small boy left sprawling, I laugh, not at the small boy, but the joke my mate has just relayed, it’s funny right. People weave left and right but me, I don’t worry, I walk straight on, embroiled in my conversation, it’s not about them, it’s about me.

There’s my friend and his family, let’s stop here, in the middle of the pavement and let’s talk. What, people are having to walk in the road to get past, I’m discussing weighty matters here, can’t you see, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

I hop on the bus, earbuds, I’m not sure where they are. Now where’s that YouTube video my mate told me about, oh yeah, here it is. Now that’s hilarious, can’t hear it because of all the hub bub around me, turn it up and enjoy, I’m having a gas. Didn’t want to listen to that? It’s not about you, it’s about me.

And now at work, I take up the laptop and watch some TED talk video, I need to go somewhere so with laptop open, speaker on full, I wander across the office and out through the door held open for me. I don’t acknowledge your politeness, I don’t see you, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

I sit waiting for a colleague to join me in an open area, people around using laptops, having conversations, I turn the volume up, this video is good, I need to hear it, it’s not about the rest of you, it’s about me.

I go to the work restaurant with my friend, it’s a bit busy, never mind we can sit here. I push my chair back banging into another chair, catching the knuckles of someone that happens to be leaning on the chair. I don’t see it, I don’t see you, I want to sit here right, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

And when I learn to drive, I’m going to speed even if it is dangerous because I will need to get to where I am going quickly, it’s not about the rest of you, it’s about me. And I will be the one that overtakes all the cars in the queue, only to push in at the last moment. My indicator tells you to give me room, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

And when I have kids, I will park right outside the school, never mind if I obstruct the road, I need to pick up my little darlings, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

And in my real world, when I have to constantly move out of the way of people on phones, have to listen to videos and conversations I have no interest in, hold doors open without even a glance from the person that has walked through, have my knuckles scraped with the back of a chair, without even an acknowledgement that something has happened, despite my yelp from the pain, when I sit watching the idiots overtaking and have to brake to avoid a collision as they push into the queue, when I sit and wait in the road whilst someone strolls along, little one in tow and straps them in the back seat before having a quick chat with another parent, I inwardly shout to myself; WHEN WAS IT THAT I BECAME INVISIBLE? I’s not just about you, it’s also about me.

Meet the Team: Liam Miles, Lecturer in Criminology

Hello!

I am Liam Miles, a lecturer in criminology and I am delighted to be joining the teaching team here at Northampton. I am nearing the end of my PhD journey that I completed at Birmingham City University that explored how young people who live in Birmingham are affected by the Cost-of-Living Crisis. I conducted an ethnographic study and spent extensive time at two Birmingham based youth centres. As such, my research interests are diverse and broad. I hold research experience and aspirations in areas of youth and youth crime, cost of living and wider political economy. This is infused with criminological and social theory and qualitative research methods. I am always happy to have a coffee and a chat with any student and colleague who wishes to discuss such topics.

Alongside my PhD, I have completed two solo publications. The first is a journal article in the Sage Journal of Consumer Culture that explored how violent crime that occurs on British University Campuses can be explained through the lens of the Deviant Leisure perspective. An emerging theoretical framework, the Deviant Leisure perspective explores how social harms are perpetuated under the logics and entrenchment of free-market globalised capitalism and neoliberalism. As such, a fundamental source of culpability towards crime, violence and social harm more broadly is located within the logics of neoliberal capitalism under which a consumer culture has arisen and re-cultivated human subjectivity towards what is commonly discussed in the literature as a narcissistic and competitive individualism. My second publication was in an edited book titled Action on Poverty in the UK: Towards Sustainable Development. My chapter is titled ‘Communities of Rupture, Insecurity, and Risk: Inevitable and Necessary for Meaningful Political Change?’. My chapter explored how socio-political and economic moments of rupture to the status quo are necessary for the summoning of political activism; lobbying and subsequent change.

It is my intention to maintain a presence in the publishing field and to work collaboratively with colleagues to address issues of criminal and social justice as they present themselves. Through this, my focus is on a lens of political economy and historical materialism through which to make sense of local and global events as they unfold. I welcome conversation and collaboration with colleagues who are interested in these areas.

Equally, I am committed to expanding my knowledge basis and learning about the vital work undertaken by colleagues across a breadth of subject areas, where it is hoped we can learn from one another.

I am thoroughly looking forward to meeting everyone and getting to learn more!

Christmas Toys

In CRI3002 we reflected on the toxic masculine practices which are enacted in everyday life. Hegemonic masculinity promotes the ideology that the most respectable way of being ‘a man’ is to engage in masculine practices that maintain the White elite’s domination of marginalised people and nations. What is interesting is that in a world that continues to be incredibly violent, the toxicity of state-inflicted hegemonic masculinity is rarely mentioned.

The militaristic use of State violence in the form of the brutal destruction of people in the name of apparent ‘just’ conflicts is incredibly masculine. To illustrate, when it is perceived and constructed that a privileged position and nation is under threat, hegemonic masculinity would ensure that violent measures are used to combat this threat.

For some, life is so precious yet for others, life is so easily taken away. Whilst some have engaged in Christmas traditions of spending time with the family, opening presents and eating luxurious foods, some are experiencing horrors that should only ever be read in a dystopian novel.

Through privileged Christmas play-time with new toys like soldiers and weapons, masculine violence continues to be normalised. Whilst for some children, soldiers and weapons have caused them to be victims of wars with the most catastrophic consequences.

Even through children’s play-time the privileged have managed to promote everyday militarism for their own interests of power, money and domination. Those in the Global North are lead to believe that we should be proud of the army and how it protects ‘us’ by dominating ‘them’ (i.e., ‘others/lesser humans and nations’).

Still in 2023 children play with symbolically violent toys whilst not being socialised to question this. The militaristic toys are marketed to be fun and exciting – perhaps promoting apathy rather than empathy. If promoting apathy, how will the world ever change? Surely the privileged should be raising their children to be ashamed of the use of violence rather than be proud of it?

Festive messages, a legendary truce, and some massacres: A Xmas story

Holidays come with context! They bring messages of stories that transcend tight religious or national confines. This is why despite Christmas being a Christian celebration it has universal messages about peace on earth, hope and love to all. Similar messages are shared at different celebrations from other religions which contain similar ecumenical meanings.

The first official Christmas took place on 336 AD when the first Christian Emperor declared an official celebration. At first, a rather small occasion but it soon became the festival of the winter which spread across the Roman empire. All through the centuries more and more customs were added to the celebration and as Europeans “carried” the holiday to other continents it became increasingly an international celebration. Of course, joy and happiness weren’t the only things that brought people together. As this is a Christmas message from a criminological perspective don’t expect it to be too cuddly!

As early as 390 AD, Christmas in Milan was marked with the act of public “repentance” from Emperor Theodosius, after the massacre of Thessalonica. When the emperor got mad they slaughtered the local population, in an act that caused even the repulson of Ambrose, Bishop of Milan to ban him from church until he repented! Considering the volume of people murdered this probably counts as one of those lighter sentences; but for people in power sentences tend to be light regardless of the historical context.

One of those Christmas celebrations that stand out through time, as a symbol of truce, was the 1914 Christmas in the midst of the Great War. The story of how the opposing troops exchanged Christmas messages, songs in some part of the trenches resonated, but has never been repeated. Ironically neither of the High Commands of the opposing sides liked the idea. Perhaps they became concerned that it would become more difficult to kill someone that you have humanised hours before. For example, a similar truce was not observed in World War 2 and in subsequent conflicts, High Commands tend to limit operations on the day, providing some additional access to messages from home, some light entertainment some festive meals, to remind people that there is life beyond war.

A different kind of Christmas was celebrated in Italy in the mid-80s. The Christmas massacre of 1984 Strage Di Natale dominated the news. It was a terrorist attack by the mafia against the judiciary who had tried to purge the organisation. Their response was brutal and a clear indication that they remained defiant. It will take decades before the organisation’s influence diminishes but, on that date, with the death of people they also achieved worldwide condemnation.

A decade later in the 90s there was the Christmas massacre or Masacre de Navidad in Bolivia. On this occasion the government troops decided to murder miners in a rural community, as the mine was sold off to foreign investors, who needed their investment protected. The community continue to carry the marks of these events, whilst the investors simply sold and moved on to their next profitable venture.

In 2008 there was the Christmas massacre in the Democratic Republic of Congo when the Lord’s Resistance Army entered Haut-Uele District. The exact number of those murdered remains unknown and it adds misery to this already beleaguered country with such a long history of suffering, including colonial ethnic cleansing and genocide. This country, like many countries in the world, are relegated into the small columns on the news and are mostly neglected by the international community.

So, why on a festive day that commemorates love, peace and goodwill does one talk about death and destruction? It is because of all those heartfelt notions that we need to look at what really happens. What is the point of saying peace on earth, when Gaza is levelled to the ground? Why offer season’s wishes when troops on either side of the Dnipro River are still fighting a war with no end? How hypocritical is it to say Merry Christmas to those who flee Nagorno Karabakh? What is the point of talking about love when children living in Yemen may never get to feel it? Why go to the trouble of setting up a festive dinner when people in Ethiopia experience famine yet again?

We say words that commemorate a festive season, but do we really mean them? If we did, a call for international truce, protection of the non-combatants, medical attention to the injured and the infirm should be the top priority. The advancement of civilization is not measured by smart phones, talking doorbells and clever televisions. It is measured by the ability of the international community to take a stand and rehabilitate humanity, thus putting people over profit. Sending a message for peace not as a wish but as an urgent action is our outmost priority.

The Criminology Team, wishes all of you personal and international peace!

Stop the boats, Stop the visas, Meet the thresholds and You are in!

The Tory party has witnessed a number of challenges in recent years and with the appointment of Rishi Sunak, a brief sense of stability was felt amidst the chaos. As different parties look to the upcoming elections, each party have begun to move pieces on its chess board. While campaigns have unofficially begun, some commentators have argued that Sunak’s recent policy on migration could be one of his game plans.

Let’s take a closer look into this recent migration policy. Attention seemed to have slowly shifted away from the plan of redirecting boats to Rwanda to the need to suppress legal migration. To restrict LEGAL migration, Sunak’s government instituted policies limiting opportunities on student visas, banning dependents on care visas, increasing the minimum income threshold for skilled worker and family visas, and revising rules around shortage occupation lists.

Starting with the skilled worker visas, the government imposed a £38,700 minimum salary requirement to gain entry into the UK. Simply put, if you are coming to work in the UK, you must search for a job that pays nothing less than £38,700 in annual income, or else you will not qualify. For me, I think some clarification is needed here for what the government considers as skilled jobs exactly. I say this because junior doctors, nurses and train operators would be considered as being part of a skilled workforce. However, these skilled work force have undertaken multiple strike action over dispute on wages in the last few months. This leads me to another question – how many ‘skilled job’ workers earn a salary of £38,700 in the current day economy? Although the government implied that the reason for this is to force organisations to look to British citizens first rather than relying on legal migrants – which could be thought as quite commendable however, a number of UK workers earn less than the new threshold annually anyway. So this logic needs further clarity in my view.

In terms of curbing student’s visas, UK higher education has long attracted international students, yet these new policies outrightly banning postgraduate dependents and targeting post-study work visas seem quite harsh, especially given the exorbitant £13,000 to £18,000 yearly tuition fees already paid by these students. If the aim is transforming education into a type of transitory/knowledge based tourism, this should be transparent so aspiring international scholars are not misled into believing they are wanted for anything beyond their hefty bank balances.

On family visas and so forth, it is without a doubt that these new rules will tear apart families because it also imposes a £38,700 minimum income threshold on family visas from £18,600. The technicality around this is that legal migrants will not be the only ones to be affected by these new rules, British citizens will also be affected. Let us consider this scenario. Consider Linda, a British citizen working part-time in retail earning £33,000 annually. She aims to marry her long-term boyfriend from Sri Lanka next summer, but both of them fall short of the minimum income threshold. Under the current rule, Linda now faces a dilemma. It’s either she increases her earnings above the threshold by the next spring or uproot her British life to reunite with her partner abroad. Contrast her plight with Kelvin, a non British citizen who has recently secured a Band 7 physiotherapy role in the NHS. He is entering the UK from Mozambique and has managed to negotiate a £47,000 pay deal with his trust. Kevin has the right to move his family freely over to the UK without any disruption. This seems more like double standards because for the less affluent, it seems the right to create a family across borders will become an exclusive privilege reserved only for the rich under this new policy.

The clock may be running out for advocacy groups hoping to see a repeal of these new regulations by the House of Lords and it seems doubtful there is enough procedural means in the Commons to withdraw the policies.

Meet the Team: Angela Charles, Senior Lecturer in Criminology

I would like to take this opportunity to say a warm hello to my colleagues and to the students at the University of Northampton.

I am Angela Charles, a senior lecturer in criminology. I have a passion and deep interest in this discipline for a number of reasons. Firstly, criminology is such a fascinating and thought-provoking subject that is constantly evolving and expanding. Secondly, criminology is a subject where I believe social justice can be fought for and in many cases achieved, through researching and gaining evidence to push for change, and through perseverance. Thirdly, criminology requires us to discuss, debate, analyse and build on what has been previously argued and discussed; thereby strengthening, tweaking or dismantling and rebuilding previous theoretical knowledge and criminological concepts.

My research interests are within prisons and penology, and race and gender. My most recent research explored and analysed the experiences of Black women in English prisons, paying particular attention to the intersections of race, class and gender. Black women are at the margins of society and face multiple intersecting oppressions. The prison is arguably a microcosm of society and perpetuates the same oppressive structural inequalities. It is often these racialised and gendered pains of imprisonment that are rarely discussed or mentioned both within scholarly literature and the public realm more widely. I hope to disseminate my research in the coming years and amplify some of the voices of Black women in UK prisons.

I’m also keen to explore research methods that arguably move away from traditional research methods and instead aim to decolonise research methods. Criminologists need to adapt the methods they use to suit the differing backgrounds and cultures of the participants that we research, and we need to incorporate different cultural aspects into the research process. I believe this not only will create richer data, but will also increase participant engagement as they become co-producers of knowledge.

Lastly, I look forward to working closely with my colleagues to learn about their research interests, passions and to collaborate on ensuring that studying criminology is enjoyable, rewarding and insightful at the University of Northampton!

Journeys Through Time: From British Empire’s Transportation Punishment to Contemporary Immigration Challenges

On November 29, 2023, our level 5 criminology students embarked on a visit to the National Museum of Justice in Nottingham. The trip had multiple objectives, including providing students with an out-of-classroom understanding of archives, immersing them in the crime and justice model in Britain from the 1840s to the 1940s, exposing them to rich historical records, deepening their understanding of archival research materials, and offering them first-hand experience on the treatment and conditions of suspected and convicted individuals in the past.

The museum, a vital historical site, not only facilitates reflection on the history of crime and justice in Britain but also offers an opportunity to ponder the trends and trajectory of changes since 1614.

Among the myriad opportunities for learning and research, transportation stood out for me. This form of punishment, prevalent in the British Empire from the 17th to the mid-19th centuries, forcibly removed convicted individuals from Britain to penal colonies, primarily in North America and later in Australia. This severe punishment involved separating convicts from their families and homeland, subjecting them to harsh and unfamiliar environments. Notably, individuals as young as nine were sent to America in 1614, with sentences ranging from 7 to 14 years or life. In addition to its punitive aspect, transportation provided forced cheap labour for the British government in exploited colonies, contributing to the expansion of the British Empire.

The deplorable conditions during transportation, its impact on the history of Australia and other colonies, and its role in the development of a unique convict society underscore its harsh and brutal nature. Despite its significant role, transportation was gradually abolished in the mid-19th century due to growing unpopularity and expense.

The historical context of transportation as a punitive measure serves as a backdrop for understanding current immigration and eviction plans in the UK, particularly concerning refugees and asylum seekers arriving in small boats. Though transportation was phased out in the mid-19th century, the echoes of forcibly moving individuals can be juxtaposed with contemporary immigration policies.

The British Empire’s transportation punishment, involving forced removal to distant penal colonies, parallels the challenges faced by today’s refugees and asylum seekers. While historical transportation was driven by criminality, current immigration plans involve vulnerable populations seeking refuge and safety, raising uncertainties about the safety they can find in Rwanda.

Examining the deplorable conditions of transportation provides a lens to scrutinize the humanitarian aspects of current immigration policies, emphasizing the toll on human life, challenges during migration, and impacts on indigenous populations.

Both transportation and the Rwanda plan share a common objective of removing unwanted individuals from British society, albeit for different reasons. Transportation aimed to punish criminals, while the Rwanda plan intends to deter dangerous journeys across the English Channel.

However, both policies face criticism from human rights groups, asserting their cruelty and violation of international law. Despite this, steps to implement the Rwanda plan are underway, indicating a willingness to sacrifice the well-being of vulnerable individuals for political expediency. The parallels between transportation and the Rwanda plan serve as a stark reminder of the dark side of British history, with asylum seekers and refugees sent to Rwanda facing the prospect of indefinite detention and potential persecution upon return to their countries of origin.

While transportation was abolished in the mid-19th century, exploring its historical significance encourages reflection on the complexities of modern immigration and eviction plans. This analysis highlights how punitive measures, whether historical or contemporary, shape societies, impact individuals, and contribute to a nation’s broader narrative.

A visual walk around a panopticon prison in the city of “Brotherly Love”

Conferences…people even within academia have views on them. This year the American Society of Criminology hosted its annual meeting in Philadelphia. In the conference we had the opportunity to talk about course development and the pedagogies in criminology. Outside the conference we visited Eastern State Penitentiary one of the original panopticon prisons…now a decaying museum on penal philosophy and policy.

The bleak corridors of a panopticon prison

the walls are closing in and there is only light from above

these cells smell of decay; they were the last residence of those condemned to death

the old greenhouse; now a glass/concrete structure…then a place to plant flowers. Even in the darkest places life finds a way to persevere

isolation: a torture within an institution of violence. The people coming out will be forever scared as time leaves the harshest wounds

a place of worship: for some the only companion to abject desperation; for those who did not lose their minds or try to end their lives; faith kept them at least alive.

the yard is monitored by the guards at the core; the chained prisoners will walk outside or get some exercise but only if they behave. To be outside in here is a privilege

the corridors look identical; you become disoriented and disillusioned

everything here conjures images of pain

an ostentatious building, build back in the 19th century to lock in criminals. It housed a new principled idea, a new system on penal reform. the first penitentiary of its kind. Nonetheless it never stopped being an institution of oppression…it closed in 1970.

The role of the criminologist (among others) is to explain, analyse and discuss our responses to crime, the systems we use and the strategies employed. So before a friendly neighbour tells you that sending people to an island or arming the police with guns or giving juveniles harsher penalties, they better talk to a criminologist first.

As a final thought, I leave you with this…there are people who left the prison broken but there are those who died in this prison. Eleven people tried to escape but were recaptured. Once you are sent down, the prison owns you.

In Praise of Howard S. Becker (1928-2023)

Three months ago, Howard S. Becker died at the age of 95, some of the Criminology Team reflect below on his impact.

I re-read Becker’s Outsider’s during the covid-19 pandemic. It reminded me of how Becker’s critical take on criminology helped me to understand and articulate the world in which I grew up in. Yes, street crime happens, and yes it causes victims to suffer but street crime seemed to be a survival response from the powerless aka ‘the deviants’ who were oppressed by the disciplining State and its police force. Becker’s work must have been groundbreaking at the time that it was published, and it continues to resonate within more contemporary critical theories surrounding intersectional oppressions that I am most interested in today…what a game changer!

@haleysread

I first encountered Becker’s (1963) Outsiders as an undergraduate, since then I have revisited many times. The book and the ideas within are so well-written, so accessible, allowing the reader to see criminality and criminal justice from an entirely different perspective. Although profound, it is not this Becker text which is closest to my heart, for that we go to 1967 and the publication of his article ‘Whose Side Are We On?‘ It is this succinct piece of writing that allowed me to understand that criminologists can never be neutral, they have to take a side. Furthermore, they must always be on the side of the powerless and never the powerful. The Criminal Justice System [CJS] and all of the agents within it, are working within and for the State and thus have plenty of supporters. Individuals in their engagement with the CJS, do not have the same support or protection, they are always outnumbered and out resourced. If we truly want to gain a holistic understanding of deviance and criminality, Becker (1967) is very helpful.

Alongside, his writing around crime and deviance, Becker also identifies the importance of language and writing style, to research practice. In Writing for Social Scientists (1986) and Tricks of the Trade (1998) and Telling About Society (2007) offers clear, practical guidance and comfort for uncertain scholars (whatever level of study).

Finally, we need to mention Becker’s music, his beloved jazz which provides the soundtrack to a scholarly life well lived, which means you can study his life’s work (both written and aural) simultaneously. A unique man, whose impact will be felt by criminologist and other social scientists for a very long time.

@paulaabowles

In 2006, during my undergraduate studies in sociology, I was introduced to Howard Becker’s labelling theory. While it marked a significant departure from the traditional explanation of deviance, it sparked lively debates among my peers. I distinctly recall vehemently opposing the theory’s practical application in Nigeria, my home country. Some of my peers argued passionately, citing numerous examples of deviance, including instances of crimes of the powerful. They contended that corruption and the misappropriation of public funds in Nigeria were products of eroding social values, driven by immense societal pressure on political officeholders to maintain an image of ‘big men.’ No doubt, Becker had a point on this and despite my initial reservations about labelling theory, Becker’s scholarly contributions have undeniably been influential in shaping both my sociological imagination and my criminological lenses. So long to a respected scholar!

@sallekmusa

It is impossible to list eminent criminologists without at least giving a nod to Howard Becker, although I would suggest a nod is far from sufficient. Becker it seems to me had the ability to write meaningful texts that could be understood by all. Of course his narrative in Outsiders is a product of its time but much of it is still applicable today. I first read Outsiders as part of my undergraduate degree and much of resonated and yet as with all great work, it doesn’t explain everything. What it does though is provide a very different perspective on deviance and society as a whole. In his later work Becker discussed labelling stating it wasn’t a theory. Well worth returning to the book then just to understand that statement alone.

@5teveh

This August 16, 2023, Howard Becker died. He was a 95 years old social scientist/sociologist (depending on who you will ask) with a long and significant legacy on his tome of work. My colleagues above predictably chose Outsiders as representative sample of his work. Not surprising really considering this was one of his seminal pieces of work that articulated the basis of theories that sociologists, criminologists and other social scientists based their own theories and understanding on social reality. His work on labelling theory became a significant influence on criminologists who tried to understand the relationship between postmodernity and deviance. It comes as no surprise that his influence to those who followed him in academia was so important.

What I thought most fitting was to concentrate on one of his latest papers written a few years ago when he was 91. In the midst of the pandemic with the lockdown and the great uncertainty it ensued Howard retreats to what he knows best; to be a social scientist and contextualise his observations the best way he knows. The paper in a praise of neighbourhood spirit and collective consciousness under the guise of urban sociology. Howard Becker is very reflective of his location, the history of the place and its social development and it is a testament of the importance of interactionism and positionality.

Using personal experience his paper “In San Francisco, when my neighborhood experiences pandemics” Becker retains his criticality as a social scientist, using observations and personal narratives to humanise an inhuman and repressive situation. People around him become actors in the crisis especially to those who as more in need and his impressions give us a snapshot of the time. In his own words “Those of us who do social science to be ready to observe life around us” a legacy to all of us that social situations continuously challenge us to explore things differently. That is because “social life does the experiment for us”. One of his last lessons on “life goes on” is so important to the sociology of everyday life.

This paper may not have the significance of some of his earlier work but it is a testament of what a restless mind can produce. He was able to record a situation that in years, decades to come, people will write about it and its impact. Yet, despite his age, his writing remained fresh, current and relevant. In academic terms he was the eternal teenager. Solon of Athens once said “Γηράσκω αεί διδασκόμενος” “I grow old while always learning” projecting that the pursue of knowledge is continuous and lifelong. In Howard Becker this seemed to have been the case. Thank you for your company all those years in the libraries, the seminars, the essays that we read you, thought of your ideas and talk about them. Goodbye to the social scientist, the thinker, the philosopher, the person.

@manosdaskalou