Home » Criminological imagination (Page 9)

Category Archives: Criminological imagination

The victimisation of one

One of the many virtues of criminology is to talk about many different crimes, many different criminal situations, many different deviant conditions. Criminology offers the opportunity to consider the world outside the personal individual experience; it allows us to explore what is bigger than the self, the reality of one.

Therefore, human experience is viewed through a collective, social lens; which perhaps makes it fascinating to see these actions from an individual experience. It is when people try to personalise criminological experience and carry it through personal narratives. To understand the big criminological issues from one case, one face, one story.

Consider this: According to the National Crime Agency over 100K children go missing in the UK each year; but we all remember the case of little Madeleine McCann that happened over 13 years ago in Portugal. Each year approximately 65 children are murdered in the UK (based on estimates from the NSPCC, but collectively we remember them as James Bulger, Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman. Over 100 people lost their lives to racially motivated attacks, in recent years but only one name we seem to remember that of Stephen Lawrence (Institute of Race Relations).

Criminologists in the past have questioned why some people are remembered whilst others are forgotten. Why some victims remain immortalised in a collective consciousness, whilst others become nothing more than a figure. In absolute numbers, the people’s case recollection is incredibly small considering the volume of the incidents. Some of the cases are over 30 years old, whilst others that happened much more recently are dead and buried.

Nils Christie has called this situation “the ideal victim” where some of those numerous victims are regarded “deserving victims” and given legitimacy to their claim of being wronged. The process of achieving the ideal victim status is not straightforward or ever clear cut. In the previous examples, Stephen Lawrence’s memory remained alive after his family fought hard for it and despite the adverse circumstances they faced. Likewise, the McGann family did the same. Those families and many victims face a reality that criminology sometimes ignores; that in order to be a victim you must be recognised as one. Otherwise, the only thing that you can hope for it that you are recorded in the statistics; so that the victimisation becomes measured but not experienced. This part is incredibly important because people read crime stories and become fascinated with criminals, but this fascination does not extend to the victims their crimes leave behind.

Then there are those voices that are muted, silenced, excluded and discounted. People who are forced to live in the margins of society not out of choice, people who lack the legitimacy of claim for their victimisation. Then there are those whose experience was not even counted. In view of recent events, consider those millions of people who lived in slavery. In the UK, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 and in the US the Emancipation Proclamation Act of 1863 ostensibly ended slavery.

Legally, those who were under the ownership of others became a victim of crime and their suffering a criminal offence. Still over 150 years have passed, but many Black and ethnic minorities identify that many issues, including systemic racism, emanate from that era, because they have never been dealt with. These acts ended slavery, but compensated the owners and not the slaves. Reparations have never been discussed and for the UK it took 180 years to apologise for slavery. At that pace, compensation may take many more decades to be discussed. In the meantime, do we have any collective images of those enslaved? Have we heard their voices? Do we know what they experience? Some years ago, whilst in the American Criminology Conference, I came across some work done by the Library of Congress on slave narratives. It was part of the Federal Writers’ Project during the great depression, that transcribed volumes of interviews of past slaves. The outcome is outstanding, but it is very hard to read.

In the spirit of the one victim, the ideal victim, I am citing verbatim extracts from two ex-slaves Hannah Allen, and Mary Bell, both slaves from Missouri. Unfortunately, no images, no great explanation. These are only two of the narratives of a crime that the world tries to forget.

“I was born in 1830 on Castor River bout fourteen miles east of Fredericktown, Mo. My birthday is December 24. […] My father come from Perry County. He wus named Abernathy. My father’s father was a white man. My white people come from Castor and dey owned my mother and I was two years old when my mother was sold. De white people kept two of us and sold mother and three children in New Orleans. Me and my brother was kept by de Bollingers. This was 1832. De white people kept us in de house and I took care of de babies most of de time but worked in de field a little bit. Dey had six boys. […] I ve been living here since de Civil War. Dis is de third house that I built on dis spot. What I think ‘bout slavery? Well we is getting long purty well now and I believe its best to not agitate”.

Hannah Allen

“I was born in Missouri, May 1 1852 and owned by an old maid named Miss Kitty Diggs. I had two sisters and three brothers. One of my brothers was killed in de Civil War, and one died here in St. Louis in 1919. His name was Spot. My other brother, four years younger than I, died in October, 1925 in Colorado Springs. Slavery was a mighty hard life. Kitty Diggs hired me out to a Presbyterian minister when I was seven years old, to take care of three children. I nursed in da family one year. Den Miss Diggs hired me out to a baker named Henry Tillman to nurse three children. I nurse there two years. Neither family was nice to me.”

Mary Bell

When people said “I don’t understand”, my job as an educator is to ask how can I help you understand? In education, as in life, we have to have the thirst of knowledge, the curiosity to learn. Then when we read the story of one, we know, that this is not a sole event, a bad coincidence, a sad incident, but the reality for people around us; and their voices must be heard.

References

Nils Christie (1986) The Ideal Victim, in Fattah Ezzat A (eds) From Crime Policy to Victim Policy, Palgrave Macmillan, London

Missouri Slave Narratives, A folk History of Slavery in Missouri from Interviews with Former Slaves, Library of Congress, Applewood Books, Bedford

Time to hear from our students

As part of their commitment to provide an inclusive space to explore a diversity of subjects, from a diverse range of standpoints, the Thoughts from the Criminology team have decided to introduce a new initiative.

From tomorrow (Sunday 21 June) all weekend posts will come from our students. We know that all of our students have plenty to say, they are smart, articulate and have both academic and experiential knowledge on which to draw. We know our readers will be as impressed as we are, by their passion and their criminological imagination.

Over to you, Criminology Students!

8 Kids and Judging

Written by @bethanyrdavies with contributions from @haleysread

Big Families are unique, the current average family size is 2.4 (Office for National Statistics, 2017) which has declined but remained as such for the past decade. Being 1 of 8 Children is unique, it’s an interesting fact both myself and Haley (also a former graduate and also 1 of 8) both fall back on when you have those awful ice breakers and you have to think of something ‘special’ about yourself.

There is criminological research which identifies ‘large families’ as a characteristic for deviance in individuals (Farrington & Juby, 2001; Wilson, 1975). It’s argued alongside other family factors, such as single-parent households, which maybe more people are familiar with in those discussions. In fact, when looking for criminological research around big families, I didn’t find a great deal. Most of what I found was not looking at deviance but how it affects the children, with suggestions of how children in big families suffer because they get less attention from their parents (Hewitt et al. 2011). Which may be the reality for some families, but I also think it’s somewhat subjective to determine an amount of time for ‘attention’ rather than the ‘quality’ of time parents need to spend with children in order to both help fulfil emotional and cognitive needs. This certainly was not the case from both Haley’s and experience.

When I first thought about writing this piece and talking to Haley about her experiences. I did question myself on how relevant this was to criminology. The answer to that I suppose depends on how you perceive the vastness of criminology as an academic field. The family unit is something we discuss within criminology all the time, but family size is not always the focus of that discussion. Deviance itself by definition and to deviate from the norms of society, well I suppose myself and Haley do both come from ‘deviant’ families.

However, from speaking with Haley and reflecting on my own experience, it feels that the most unique thing about being part of a large family, is how others treat you. I would never think to ask anyone or make comments such as; “How much do your parents earn to look after you all?” or “Did they want a family that big or was it lots of accidents?” or even just make comments, about how we must be on benefits, be ‘Scroungers’ or even comments about my parents sexual relationship. Questions and comments that both I and Haley have and occasionally still experience. Regardless of intent behind them, you can’t help but feel like you have to explain or defend yourself. Even as a child when others would ask me about my family, I had always made a point of the fact that we are all ‘full siblings’ as if that could protect me from additional shame , shame that I had already witnessed in conversations and on TV, with statements such as “She’s got 5 kids all different dads”. Haley mentioned how her view of large families was presented to her as “Those on daytime television would criticise large families” and “A couple of people on our street would say that my parents should stop having kids as there are enough of us as it is.”

Haley and I grew up in different parts of the UK. Haley grew up in the Midlands and describes the particular area as disadvantaged. Due to this Haley says that it wasn’t really a problem of image that the family struggled financially, as in her area everyone did, so therefore it was normal. I grew up in a quite affluent area, but similar to Haley, we were not well-off financially. My childhood home was a council house, but it didn’t look like one, my mum has always been house proud and has worked to make it not look like a council house, which in itself has its own connotations of the ‘shame’ felt on being poor, which Haley also referenced to me. It was hard to even think of labeling us as ‘poor’, as similar to Haley, we had loads of presents at Christmas, we still had nice clothes and did not feel like we were necessarily different. Though it appears me and Haley were also similar in that both our dads worked all the hours possible, I remember my dad worked 3 jobs at one point. I asked my dad about what it was like, he said it was very hard, and he remembers that they were working so hard because if they went bankrupt, it would be in the newspaper and the neighbors would see. Which I didn’t even know was something that happened and has its own name and shame the poor issues for another post. Haley spoke of similar issues and the stress of ‘childcare and the temporary loss of hot water, electric and gas.’

The main points that came from both mine and Haley’s discussions were actually about how fun it is to have a large family, especially as we were growing up. It may not seem like it from my earlier points around finance, but while it was a factor in our lives, it also didn’t feel as important as actually just being a part of that loving family unit. Haley put it perfectly as “I loved being part of a large family as a child. My brothers and sisters were my best friends”. We spoke of the hilarity of simple things such as the complexities of dinner times and having to sit across multiple tables to have dinners in the evening. I had brothers and sisters to help me with my homework, my eldest sister even helped me with my reading every night while I was in primary school. Haley and I both seemed to share a love for den making, which when your parents are big into DIY (almost a necessity when in a big family) you could take tools and wood to the forest and make a den for hours on end. There is so much good about having a large family that I almost feel sorry for those who only believe the negatives. This post was simply to share a snippet of my findings, as well as mine and Haley’s experience. At the very least I hope it will allow others to think of large families in an alternative way and to realise the problems both me and Haley experienced, weren’t necessarily solely linked to our family size, but rather attitudes around social norms and financial status.

References:

Juby, H. and Farrington, D., 2001. Disentangling the Link between Disrupted Families and Delinquency: Sociodemography, Ethnicity and Risk Behaviours. The British Journal of Criminology, 41(1), pp.22-40.

Office for National Statistics. (2017). Families and households in the UK, Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/bulletins/familiesandhouseholds/2017 (Accessed: 5th June 2020).

Regoli, R., Hewitt, J. and DeLisi, M., 2011. Delinquency In Society. Boston: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Wilson, H., 1975. Juvenile Delinquency, Parental Criminality and Social Handicap. The British Journal of Criminology, 15(3), pp.241-250.

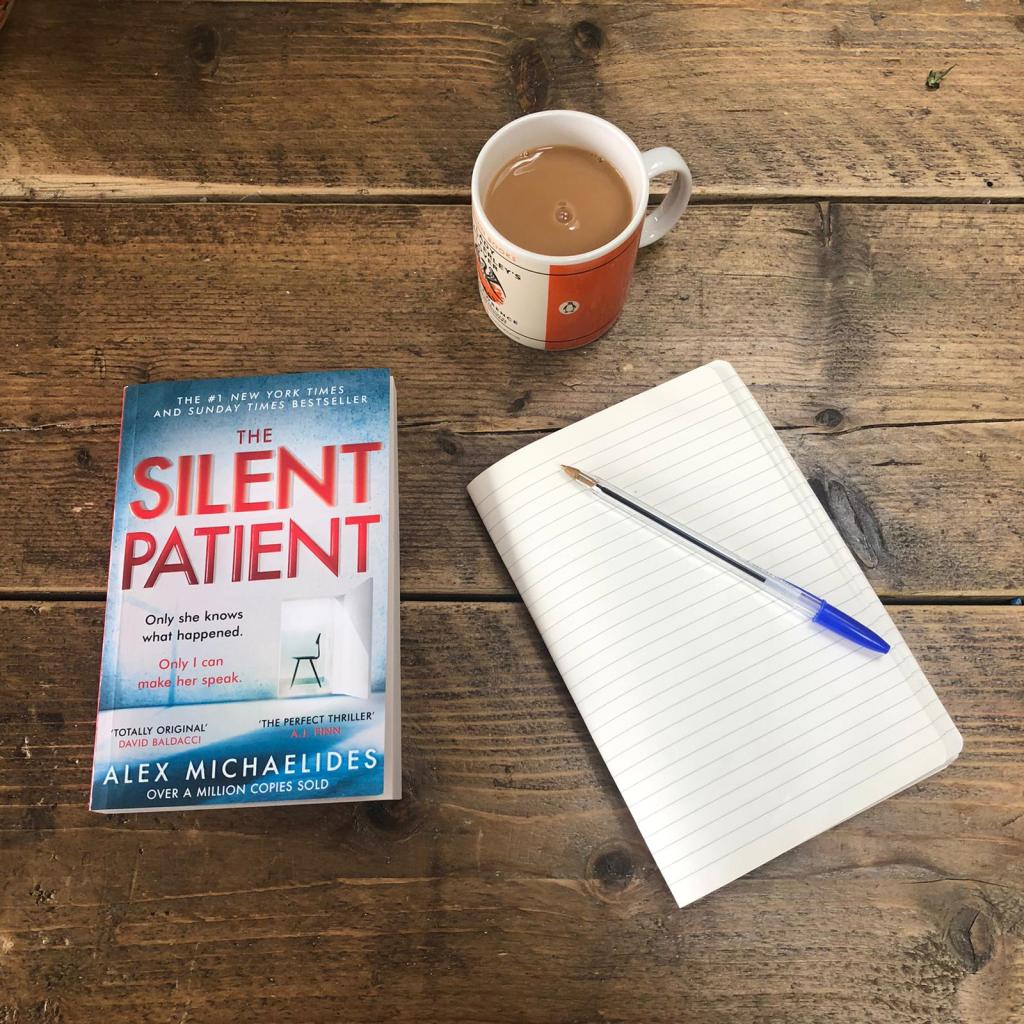

#Criminology Book Club: The Silent Patient

As you know from our last #CriminologyBookClub entry a small group of us decided the best way to thrive in lockdown was to seek solace in reading and talking about books. Building on the success of the last blog entry, we’ve decided to continue with all seven bloggers contributing! Our third book was chosen by @5teveh and it’s got us all talking! Without more ado, let’s see what everyone thought:

I enjoyed reading The Silent Patient – it was a quick and gripping read that kept me guessing (and second guessing!) throughout. I found it almost impossible to put down and could have happily read it in one sitting if time allowed. I didn’t empathise with many of the characters however, and found a couple of the plot points frustrating. I’d still recommend it though!

@saffrongarside

This is a psychological thriller that embraces Greek drama and pathos. From the references to Alcestis by Euripides and the terrible myth of death swapping to the dutiful Dr Diomedes, the characters are lined up as they are preparing from their dramatic solo. The doctor is trying to become a comforting influence in the fast pace of the story only to achieve the exact opposite. In the end he leaves in a puff of smoke from one of his cigars. The background of this story is played in a psychiatric facility, that is both unusual and conducive to amplify the flaws of the characters. This is very reminiscent of all Greek tragedies where the hero/heroine is to meet their retribution for their hubris. Once punishment comes the balance of the story is restored. This norm seems to be followed here.

@manosdaskalou

Well done to @Steve for selecting the anxiety inducing book that is The Silent Patient. I found it difficult to put this book down, as it was easy to read and a definite page turner. Once I started reading, I desperately wanted to find out what had actually happened. If Alicia had a perfect life then why would she shoot her husband FIVE TIMES in the head? It’s difficult to say much about this book without giving the plot away. I did feel for Alicia as she was surrounded by a sea of creepy and unlikable characters. Some might find the portrayal of mental health and Alicia (as the main female character) slightly insulting. Although, as we discussed in the book club, perhaps we should see this book for the thriller that it- and not try to criminologically analyse it?! As far as thrillers go, I think the book is a very good read.

@haleysread

The Silent Patient is 339 pages of suspense-filled, gripping fiction which leaves the reader with their jaw wide open. As a novel it is brilliant. Binge-worthy, unbelievable and yet somehow believable: that is until you have finished the book, and you sit back and start to pull the novel apart. DO NOT DO THIS! Get lost in the story of Theo and Alicia, be gripped and seated on the edge of your seat. It is worthy of the hype (in my humble opinion)!

@jesjames50

The Silent Patient is without a doubt a page turner! From start to finish the mystery of Alicia Berenson’s silence keeps you guessing. It is important for me to warn perspective readers that, when you start reading, it is difficult to put down, so clear your schedule. Throughout the novel you are guided through the complex life of psychotherapist Theo Faber and his mission to understand and connect with his patient that has ‘refused’ to talk, after she is found guilty of killing her husband. Alicia Berenson is admitted to a mental health hospital. This is the backdrop to disturbing yet intriguing story of how Alicia’s seemingly perfect life comes crashing down. With quirky characters, shocking revelations and suspense throughout The Silent Patient is a must read. Don’t take the story at face value, as there is a brilliant twist at the end.

As is only right and proper, we’ll leave the final word to @5teveh, after all he did choose the book 🙂

@svr2727

Not the normal sort of book I’d read, I was drawn in by the comments on the cover. It is impossible to warm to any character in The Silent Patient. The book is quite fast paced, and the writing makes it a real page turner. If you think you’ve got it, you are probably wrong. This is not a usual ‘who done it’ narrative. There are twists and turns that lead the reader through a small maze of sub plots involving characters in a tight setting. If you are looking for a hero or heroine and a happy ending, this is not the book for you. An enjoyable read in a sadistic sort of way.

@5teveh

That old familiar feeling

It would seem it’s human nature to seek out similarities in times of uncertainty. An indication that someone somewhere has experience they can share. Some sort of wisdom they can provide or at the very least a recognisable element that can somehow be interpreted to give an indication, that when it happened before everything turned out ok in the end. With the current world pandemic leaving so much free time to think and observe what is going on, one has to wonder at some point if the differences should be a more prominent focus point.

Historically world pandemics are not new. The plague, small pox, Spanish flu, all form part of a collective historical account of the global devastating impacts a new disease has on mankind. I found myself re-reading The Plague (Camus, 1947/2002) and pondering the similarities. Self-isolation and whole town isolation, the socioeconomic impacts on the poor seeking employment, despite the risk to health these roles carried and the heart-breaking accounts of families unable to say goodbye to loved ones or bury the dead in a dignified, ordinary manner.

Early on politicians and media were quick to compare the pandemic with war. Provocative language became commonplace. Talk of fighting the invisible enemy in the new ‘war’, with the ‘frontline’ NHS staff our new heroes giving the country hope we could win. It came as no surprise to wake one morning and see ‘memes’ shared on social media portraying Boris Johnson as the new Churchill.

Media quickly changed. Suddenly films which dramatised pandemics grew in popularity. These fictitious accounts of how the world would respond, the mistakes which would be made and the varying outcomes individual responses towards official advice would have on their chances of survival. Even I have to admit a scene from Contagion discussing the use of hand washing and refraining from touching your face seemed to echo government advice. Fortunately, the scenes of supermarket looting were overdramatic but the empty supermarket shelves and panic buying hysteria was all the same.

There were however, some comparisons made, which haunted me. I’m sure everyone has their own reasons for finding distaste and maybe mine were unique to me. A combination of my academic knowledge and background mixed amongst my own personal views and current situation. As a mother of three, I had suddenly become a teacher with the closure of schools. My recent master’s degree in education fortunately allowed me a basic, self-researched understanding of mainstream education and home education methods.

I watched as friends and family members concerns grew about how they as parents could provide an education. Initially most looked-for similarities once again. Similar timetables to school, similar methods of teaching, trying as a parent to morph into a similar role their children’s teacher has. I think most parents felt overwhelmed quite early on. Many most likely still do, because the thing is, home education is not comparable to mainstream education in many ways at all. That’s not to say one is superior, this is certainly not my opinion. Quite simply, they’re fundamentally different approaches.

I often find myself throughout my academic journey looking for comparison with concepts and areas in which I’m familiar. My undergrad in law and criminology makes occasional appearance in most of my writing, perhaps more often than not, in fact, I used my continued interest in criminological and legal concepts to make my education MA my own. Further reinforcing the idea, familiarity provides some sort of comfort as we enter something unknown.

One comparison which deeply worried me that finds its roots in criminological concepts, is those who have compared self-isolation with prison. Having experienced a long, heated debate previously following a comment I made displaying my disgust for the re-introduction of the death penalty, it seemed futile to raise the issues with this in the only social environment I had access to currently, social media. I remain hopeful, most criminologists recognise the obvious differences between the two.

In the end when we look back at this moment in history, there will no doubt be many more comparisons made. We often look to history to learn lessons and I’m not sure we can do that without recognising some sort of parallels with the situation. Whether that be for comfort, guidance, information or to learn, entirely depends on the individual. I will leave you with a quote of something I heard a few days ago which has stuck with me and provided inspiration for this writing…

“History doesn’t repeat itself but it often rhymes”

With that in mind, I would suggest we take comfort in the familiarity of similar situations, that this pandemic won’t last forever, but the difference it may make on our lives will always be our personal experiences. When we look back and search for comparison of life during the pandemic and life afterwards, we may well appreciate the experiences we once took for granted.

Reference

Camus, A (2002). The Plague. London: Penguin classics

“My Favourite Things”: Paula

My favourite TV show - I am not really one for television, but I recently stumbled upon a 1960's series, called The Human Jungle, lots of criminological and psychological insight, which I adore. I also absolutely loved Gentleman Jack (broadcast on BBC1 last summer) My favourite place to go - Wherever I go the first thing I look for are art galleries, so I would have to say Tate Modern. Always something new and thought provoking, alongside the familiar and oft visited treasures My favourite city - I love cities and my favourite, above all others, is the place I was born, London. The vibrancy, the people, the places, the atmosphere....need I say more? My favourite thing to do in my free time - Read, read, read, read, read, read, read, read...... My favourite athlete/sports personality - This is tricky, sport isn't really my thing. However, I do have a secret penchant for boxing, which isn't brilliant for someone who identifies as pacifist, so I'll focus on feminism and pick Nicola Adams My favourite actor - (Getting easier) Dirk Bogarde My favourite author - (Too easy) Agatha Christie My favourite drink - Day or night? If the former, tea.... My favourite food - Chocolate, always My favourite place to eat - So many to choose from, but provided I am surrounded by people I love, with good food and drink, I'm happy I like people who - read! I don’t like it when people - claim to be gender/colour blind....sorry mate, check your privilege My favourite book - (oooh very, very tricky) Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own primarily because of the profound effect it had and continues to have on my understanding My favourite book character - (Easy, peasy) Hercule Poirot My favourite film - (Despite my inner feminist screaming nooooooooo) The original Alfie with its wonderful swinging sixties' vibe My favourite poem - (Decisions, decisions, so many wonderful poems to choose from) I'll plump for Hollie McNish's Mathematics My favourite artist/band - The Beatles My favourite song - (Given the previous answer) it has to be Dear Prudence My favourite art - I love art, but hands down Picasso's Guernica is my favourite piece. To stand in front of that huge painting and consider the horror of war is profound My favourite person from history - The pacifist, suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst, a beautiful example of the necessity to be confident in your own ethics and principles

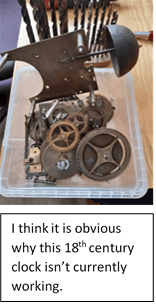

The logic of time

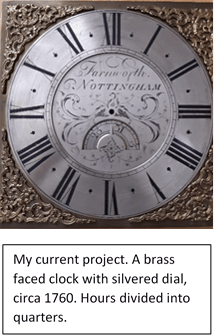

So why the love of clocks, well I’m sure some of it has to do with my propensity to logic. Old clocks are mechanical, none of this new fangled electronic circuitry and consequently it is possible to see how they operate. When a clock doesn’t work, there is always some logical reason why this is so, and a logical approach needed to fix it.

This then gives me the opportunity to investigate, explore the mechanics of the clock, work out how it ought to operate and set about repairing it. In doing so I am often handling a mechanism that is over a hundred years old, in the case of my current project, nearly three hundred years old.

There is a sense of wonderment in handling all the parts. Some appear quite rudimentary and yet other parts such as the cogs are precision pieces. Many of the parts are made by hand but clearly some are made by machines albeit fairly crude ones. How the makers managed the precision required to ensure that cogs mesh freely baffles me. What is clear though is that the makers of the clocks were skilled artisans and possessed skills that I dare say have all but been lost over the years.

Messing around with clocks (I can’t say I do more than that) also allows me to delve into history. The clock I’m currently tinkering with only has an hour hand, no minute or second hand. Whilst the hours and half hours are clearly marked on the dial, where you would normally expect to see minutes, the hours are simply divided up into quarters. A bit of social history, people didn’t have a need to know minutes, they were predominantly only concerned with the hour.

My pride and joy, a grandfather clock, dates to the 1830s. When I took it apart I found several dates and a name scratched into the back of the face plate. The dates related to when it had been serviced and by whom. I was servicing a clock that had been handled by someone over a hundred and fifty years previously. I bet they weren’t standing in a nice warm house drinking a hot cup of coffee contemplating how to service the clock. We take so much for granted and I guess the clocks allow me to reflect on what it was like when they were made and how lucky we are now. Although I do also wonder whether simple notions such as not having the need to concern ourselves with every minute might not be better for the soul.

What’s in the future for criminology?

This year marks 20 years that we have been offering criminology at the University of Northampton and understandably it has made us reflect and consider the direction of the discipline. In general, criminology has always been a broad theoretical discipline that allows people to engage in various ways to talk about crime. Since the early days when Garofalo coined the term criminology (still open to debate!) there have been 106 years of different interpretations of the term.

Originally criminology focused on philosophical ideas around personal responsibility and free will. Western societies at the time were rapidly evolving into something new that unsettled its citizens. Urbanisation meant that people felt out of place in a society where industrialisation had made the pace of life fast and the demands even greater. These societies engaged in a relentless global competition that in the 20th century led into two wars. The biggest regret for criminology at the time, was/is that most criminologists did not identify the inherent criminality in war and the destruction they imbued, including genocide.

In the ashes of war in the 20th century, criminology became more aware that criminality goes beyond individual responsibility. Social movements identified that not all citizens are equal with half the population seeking suffrage and social rights. It was at the time the influence of sociology that challenged the legitimacy of justice and the importance of human rights. In pure criminological terms, a woman who throws a brick at a window for the sake of rights is a crime, but one that is arguably provoked by a society that legitimises inequality and exclusion. Under that gaze what can be regarded as the highest crime?

Criminologists do not always agree on the parameters of their discipline and there is not always consensus about the nature of the discipline itself. There are those who see criminology as a social science, looking at the bigger picture of crime and those who see it as a humanity, a looser collective of areas that explore crime in different guises. Neither of these perspectives are more important than the other, but they demonstrate the interesting position criminology rests in. The lack of rigidity allows for new areas of exploration to become part of it, like victimology did in the 1960s onwards, to the more scientific forensic and cyber types of criminology that emerged in the new millennium.

In the last 20 years at Northampton we have managed to take onboard these big, small, individual and collective responses to crime into the curriculum. Our reflections on the nature of criminology as balancing different perspectives providing a multi-disciplinary approach to answering (or attempting to, at least) what crime is and what criminology is all about. One thing for certain, criminology can reflect and expand on issues in a multiplicity of ways. For example, at the beginning of 21st terrorism emerged as a global crime following 9/11. This event prompted some of the current criminological debates.

So, what is the future of criminology? Current discourses are moving the discipline in new ways. The environment and the need for its protection has emerge as a new criminological direction. The movement of people and the criminalisation of refugees and other migrants is another. Trans rights is another civil rights issue to consider. There are also more and more calls for moving the debates more globally, away from a purely Westernised perspective. Deconstructing what is crime, by accommodating transnational ideas and including more colleagues from non-westernised criminological traditions, seem likely to be burning issues that we shall be discussing in the next decade. Whatever the future hold there is never a dull moment with criminology.

“TW3” in Criminology

In the 1960s, or so I am told, there was a very popular weekly television programme called That Was The Week That Was, informally known as TW3. This satirical programme reflected on events of the week that had just gone, through commentary, comedy and music. Although the programme ended before I was born, it’s always struck me as a nice way to end the week and I plan to (very loosely) follow that idea here.

This week was particularly hectic in Criminology, here are just some of the highlights. On Monday, I was interviewed by a college student for their journalism project, a rather surreal experience, after all, ‘Who cares what I think?’

On Tuesday, @manosdaskalou and I, together with a group of enthusiastic third years, visited the Supreme Court in London. This trip enabled a discussion which sought to unpack the issue of diversity (or rather the lack of) within justice. Students and staff discussed a variety of ideas to work out why so many white men are at the heart of justice decisions. A difficult challenge at the best of times but given a new and urgent impetus when sat in a courtroom. It is difficult, if not impossible, to remain objective and impartial when confronted with the evidence of 12 Supreme Judges, only two of which are women, and all are white. Arguments around the supposed representativeness of justice, falter when the evidence is so very stark. Furthermore, with the educational information provided by our tour guide, it becomes obvious that there are many barriers for those who are neither white nor male to make their way through the legal ranks.

Wednesday saw the culmination of Beyond Justice, a module focused on social justice and taught entirely in prison. As in previous years, we have a small ceremony with certificate presentation for all students. This involves quite a cast, including various dignitaries, as well as all the students and their friends and family. This is always a bittersweet event, part celebration, part goodbye. Over the months, the prison classroom leaves its oppressive carceral environment behind, instead providing an intense and profound tight-knit learning community. No doubt @manosdaskalou and I will return to the prison, but that tight-knit community has now dissipated in time and space.

On Thursday, a similarly bitter-sweet experience was my last focused session this year on CRI3003 Violence: From Domestic to Institutional. Since October, the class has discussed many different topics relating to institutional violence focused on different cases including the deaths of Victoria Climbié, Blair Peach, Jean Charles de Menezes, as well as the horror of Grenfell. We have welcomed guest speakers from social work, policing and the fire service. Discussions have been mature, informed and extremely sensitive and again a real sense of a learning community has ensued. It’s also been my first experience of teaching an all-female cohort which has informed the discussion in a variety of meaningful ways. Although I haven’t abandoned the class, colleagues @manosdaskalou and @jesjames50 will take the reins for a while and focus on exploring interpersonal violence. I’ll be back before the end of the academic year so we can reflect together on our understanding of the complexity of violence.

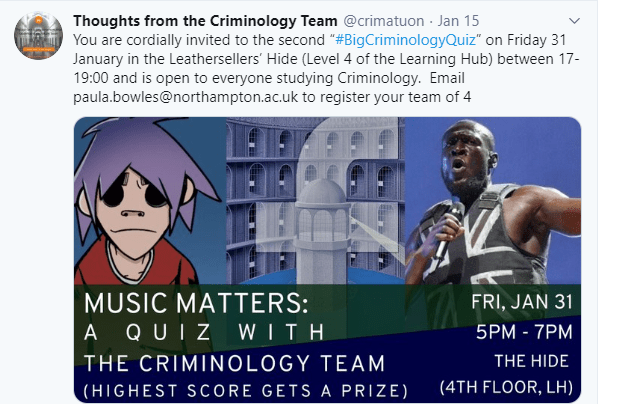

Finally, Friday saw the second ever #BigCriminologyQuiz and the first of the new decade. At the end of the first one, the participants requested that the next one be based on criminology and music. Challenge completed with help from @manosdaskalou, @treventoursu, @svr2727, @5teveh and @jesjames50. This week’s teams have requested a film/tv theme for the next quiz so we’ll definitely have our work cut out! But it’s amazing to see how much criminological knowledge can be shared, even when you’re eating snacks and laughing. [i]

So, what can I take from my criminological week:

- Some of the best criminological discussions happen when people are relaxed

- Getting out of the classroom enables and empowers different voices to be heard

- Getting out of the classroom allows people to focus on each and share their knowledge, recognising that

- A classroom is not four walls within a university, but can be anywhere (a coach, a courtroom a prison, or even the pub!)

- A new environment and a new experience opens the way for discord and dissent, always a necessity for profound discussion within Criminology

- When you open your eyes and your mind you start to see the world very differently

- It is possible (if you try very hard) to ignore the reality of Friday 31 January 23:00 ☹

- It is possible to be an academic, tour guide, mistress of ceremonies and quiz mistress, all in the same week!

Here’s looking forward to next week….not least Thursday’s Changemaker Awards where I seem to have scored a nomination with my #PartnerinCriminology @manosdaskalou.

[i] The first quiz was won by a team made up of 1st and 2nd years. This week’s quiz was won by a group of third years. The next promises to be a battle royale 😊 These quizzes have exposed, just how competitive criminologists can be….