Home » Criminals

Category Archives: Criminals

Crime I: Nature or Nurture?

This is a two-part blog on embracing some of the criminological theory origin stories in the Western hemisphere. Is crime the product of bad genes or bad society? Are we born or made criminal?

In this week we shall be exploring our understanding of biological theories originating back in the 19th century with the “born criminal”. The following week we will look at the role of the environment.

The born criminal.

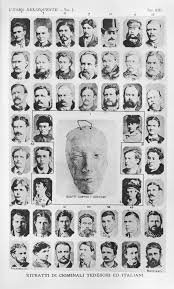

In 1871 Cesare Lombroso became the director at the Pesaro Mental Health Hospital (asylum) that housed the clinically insane. In that environment he examined the anatomical anomalies of residents in laboratory conditions. The era of the scientific exploration of deviance had begun. These meticulous explorations of bodily features and skulls formed the basis for his later thesis on The Born Criminal. The basis of his criminal population were residents of the asylum. His control group (i.e. those deemed non-criminal) were soldiers. Later, these were combined with the population of inmate prison population Lombroso and his associates visited. As he assumed an academic role in one of the finest Italian universities the world read his seminal publication of L’uomo delinquente {The Born Criminal] .Which in 1876 became one of the publications that influence the work of its contemporaries. In later years studied in exactly the same way. criminality in women using sex workers and prisoners as his research population cumulating into the 1893 publication of La Donna Delinquente: La prostituta e la donna normale [The Criminal Woman: The Prostitute and the Normal Woman.

His theoretical reach transcended borders and became widely read in the English-speaking world. This is an origin story according to numerous textbooks about the biological understanding of criminality. When embellished with some of the original quotes this becomes a theory of crime that explains different criminalities and makes the most significant leap that combines scientific rationale with crime. The methodology of anthropometry is a careful measuring of human features, prominently skulls! The main theoretical “innovation” was the recognition of a state of atavism; a regression onto a prior evolutionary stage for those engaged in crime.

A theory of crime on the born criminal seemed as a logical step at a time hailed as an era of discovery and exploration. A time that social and political movements in Europe asked profound questions about self and society. This narrative of course largely overlooks that whilst West European and US philosophers are posing these questions their elites and establishment are preoccupied with colonialism and dominance. In fact, it is the time European conflict around the world for dominance intensified. By the late 19th century, the European powers will try to manage their dominance in other continents by carving the world according to their own interests. The Berlin conference of 1884-85 is the culmination of such European competition and led to the split of Africa into zones of colonial influence.

In what way is The Born Criminal related with colonialism?

The theory of the “born criminal” breaks down humanity into two; the “normals” and the “atavists” which conveniently separates us from them. The criminal becomes the outcome of a lack of civilisation that can be seen in their physical features. There is history in separating people for the sake of exploitation, subjugation and even genocide. In this context of using civilisation (solely European) as the feature of separation is something previously seen in the colonisation of the Americas. When the European explorers landed in a new (for their map’s) continent the question of whom it belongs to was answered using religious decree. Several popes described the native population of these “discovered lands” as uncivilised and unworthy of human rights. It was the papal “Doctrine of Discovery” that denied the indigenous people rights to their land because uncivilised, faithless people (calling it terra nullus or empty land) do not count. Therefore, this separation for discrimination is not new, but Lombroso brought some scientific veneer to it.

It is important to remind all that “the born criminal” theory was widely discredited already in the early 20th century, when data analysis found no support for atavism and the biological features seemingly associated with criminality. Yet still this approach seems to capture even today some interest in the collective criminological imagination. Can you tell the prospective criminality reflected in someone’s gaze? It is a question that people still wonder, despite any lack of empirical or scientific data. The line of separating criminals from non-criminal provides an arbitrary differentiation that offers some clarity of how criminals should look, in a similar fashion to separating the “civilised” from the “savages”. In this overreaching correlation crime becomes the act of the uncivilised. It can also be flipped over and the uncivilised are the criminals contributing to the continuous fear of those who see the foreigner with suspicion.

A theory about the biological origins on crime that has offered us an explanation of the born criminal that has no scientific evidence but carries populist imagination because we take comfort in differentiating people. Next week we shall be exploring a theory that explores of the environmental factors of crime.

A new model for policing: same old rhetoric, same old politics, same old reality

The Home Secretary’s White Paper ‘From Local to National: A New Model for Policing’ promises a complete revamp of policing in England and Wales. The Northamptonshire Police Federation website provides a fairly good synopsis of what the white paper contains. Although one does hope that they didn’t resort to the use of AI to produce it otherwise they may find themselves going the same way as the beleaguered former chief constable of the West Midlands Police.

When listening to the Home Secretary Shabana Mahmood’ address to parliament regarding these reforms, I am reminded of a timeless quote from Robert Reiner regarding a former Home Secretary, Michael Howard’s address to parliament regarding another Home Office police reform White Paper back in the early 1990s. Michael Howard had stated that ‘the job of the police was to catch criminals’ and Robert Reiner, if I remember the quote correctly, stated that this statement was ‘breathtaking in its audacious simple mindedness’.

My bookshelf used to be full of Home Office White papers regarding police reform. If I went through every one of them, I would find almost all the suggestions, in one form or another, being put forward by this Home Secretary. It is like revisiting my former reality, change for change’s sake to detract from a poor performing government. Although no one could have guessed that Lord Mandelson would quickly hog the news and railroad the political landscape.

The police don’t do themselves any favours, you’ve only got to look at the headlines over the decades to know that. But of course, policing is not easy and sometimes hitting the headlines for the wrong reasons is inevitable. Rarely do the police hit the headlines for the right reasons, not because there aren’t plenty of right reasons, they simply aren’t newsworthy. However, every failure or perceived failure is ammunition for the ambitious politician and police reform is always a headline grabbing option and a distraction from other politically difficult and damning matters.

Let’s be clear, policing doesn’t happen in a vacuum. Policing relies on the public; it relies on other institutions within the criminal justice system and outside of it and it relies on good governance. If the police are underfunded, then the service they deliver to the public is substandard and this then dents confidence in the police which in turn impacts public co-operation. If the other institutions within the criminal justice system are poorly funded such as the courts, then it doesn’t matter what the police do, cases do not get to court in a timely manner, the public withdraw their support and cases collapse. If prisons are overcrowded due to lack of funding and other issues, the courts can’t function correctly and the public lose confidence. As an aside remember the furore around the wrong prisoners being released and the number of prisoners wrongly released over a year. Funny how that seems to have disappeared from the news.

But the problems for policing and the rest of the judicial system pale into insignificance when compared to the issues with underfunding in areas of social services, welfare, the NHS, education and so much more. It is easy to point to policing when the key areas that impact the public the most are decimated. People don’t just commit crime because they are greedy, they don’t resort to violence for absolutely no reason. And it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to work out that if you stop supporting young people, stop giving them hope for a future, stop keeping them engaged in meaningful activities when they are out of school then you will see crime and anti-social behaviour spiral out of control. And of course, its not just young people that feel the impact. Not so long ago there was a movement towards defunding the police. The ideas behind the movement were sound but I think perhaps a little naïve. But what was right was the idea of pouring more money into welfare and youth services. Crime is so much more than just policing, and the police have very little control over it, despite all the rhetoric.

As for policing, the white paper is just a rehash of the same old ideas and another way of wasting public money, not dissimilar to that in 2006 when another Home Secretary decided on police mergers which saw millions spent before the idea was shelved as too expensive. The police have adapted to issues identified by HMIC prior to the proposed mergers in 2006. Collaboration between forces works well, saves money and enables smaller forces to deal with large scale issues. There is no evidence anywhere that big is better. In fact there is plenty of evidence to suggest that it may not be.

If the police have retracted from neighbourhood policing it is because of underfunding. Austerity measures introduced in 2010/11 decimated police forces and their ability to deliver both neighbourhood and response policing. Neighbourhood policing became a luxury and coincidentally was also the area where instant savings could be made. Police Community Support Officers could be shed because unlike police officers, they can be made redundant. As for vetting, something that has grabbed the headlines, well what did you expect? Cut the budgets and those important but less immediate functions are also decimated. Add to this the political pressure to recruit 20,000 officers in a short space of time and you have a recipe for disaster.

I do wonder whether those chief officers that support the latest police reform agenda do so because they really understand policing and its history or because they are naïve or ambitious or perhaps a bit of both. To return to Robert Reiner, the reforms are quite simply ‘breathtaking in their audacious simple mindedness’ and the sooner they are shelved the better.

#UONCriminologyClub: What should we do with an Offender? with Dr Paula Bowles

You will have seen from recent blog entries (including those from @manosdaskalou and @kayleighwillis21 that as part of Criminology 25th year at UON celebrations, the Criminology Team have been engaging with lots of different audiences. The most surprising of these is the creation of the #UONCriminologyClub for a group of home educated children aged between 10-15. The idea was first mooted by @saffrongarside (who students of CRI1009 Imagining Crime will remember as a guest speaker this year) who is a home educator. From that, #UONCriminologyClub was born.

As you know from last week’s entry @manosdaskalou provided the introductions and started our “crime busters” journey into Criminology. I picked up the next session where we started to explore offender motivations and society’s response to their criminal behaviour. To do so, we needed someone with lived experience of both crime and punishment to help focus our attention. Enter Feathers McGraw!!!

At first the “crime busters” came out with all the myths: “master criminal” and “evil mastermind” were just two of the epithets applied to our offender. Both of which fit well into populist discourse around crime, but neither is particularly helpful for criminological study, But slowly and surely, they began to consider what he had done (or rather attempted to do) and why he might be motivated to do such things (attempted theft of a precious jewel). Discussion was fast flowing, lots of ideas, lots of questions, lots of respectful disagreement, as well as some consensus. If you don’t believe me, have a look at what Atticus and had to say!

We had another excellent criminology session this week, this time with Dr Paula Bowles. I think we all had a lot of fun, I personally could have enjoyed double or triple the session time. Dr Bowles was engaging, fun and unpretentious, making Criminology accessible to us whilst still covering a lot of interesting and complex subjects. We discussed so many different aspects of serious crime and moral and ethical questions about punishment and the treatment of criminals. During the session, we went into some very deep topics and managed to cover many big ideas. It was great that everyone was involved and had a lot to say. You might not necessarily guess from what I’ve said so far, how we got talking about Criminology in this way. It was all through the new Aardman animations film Wallace and Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl and the cheeky little penguin or is it just a chicken? Feathers McGraw. Whether he is a chicken or a penguin, he gave us a lot to discuss such as whether his trial was fair or not since he can’t talk, if the zoo could really be counted as a prison and, if so was he allowed to be sent there without a trial? Deep ethical questions around an animation. Just like last time it was a fun and engaging lesson that made me want to learn more and more and I can’t wait for next time. (Atticus, 14)

What emerged was a nuanced and empathetic understanding of some key criminological debates and questions, albeit without the jargon so beloved of social scientists: nature vs. nurture, coercion and manipulation of the vulnerable, the importance of human rights, the role of the criminal justice system, the part played by the media, the impetus to punish to name but a few. Additionally, a deep philosophical question arose as to whether or not Aardman’s portrayal of Feathers’ confinement in a zoo, meant that as a society we treat animals as though they are criminals, or criminals as though they are animals. We are all still pondering this particular question…. After deciding as group that the most important thing was for Feathers to stop his deviant behaviour, discussions inevitably moved on to deciding how this could be achieved. At this point, I will hand over to our “crime busters”!

What to do with Feathers McGraw?

At first, I thought that maybe we should make prison a better place so that he would feel the need to escape less. It wouldn’t have to be something massive but just maybe some better furniture or more entertainment. Also maybe make the security better so that it would be harder to break out. If we imagine the zoo as the prison, animals usually stay in the zoo for their life so they must have done some very bad stuff to deserve a life sentence! Is it safe to have dangerous animals so close to humans? Feathers McGraw might get influenced by the other prisoners and instead of getting better he might get more criminal ideas. I believe there should be a purpose-built prison for the more dangerous criminals, so they are kept away from the humans and the non-violent criminals. in this case is Feathers considered a violent or non-violent criminal? Even though he hasn’t killed anyone, he has abused them, tried to harm them, hacked into Wallace’s computer, vandalised gardens through the Norbots, and stole the jewel. So, I think we should get a restraining order against Feathers McGraw to stop him from seeing Wallace and Gromit. I also think we should invest in therapy for Feathers to help him realise that he doesn’t need to own the jewel to enjoy it, what would he even do with it?! Maybe socializing could also help to maybe take his mind of doing criminal things. He always seems alone and sad. I’m not sure whether he will be able to change his ways or not but I think we should do the best we can to. (Paisley, 10)

I think in order to stop Feathers McGraw’s criminal behaviour, he should go to prison but while he is there, he should have some lessons on how to be good, how to make friends, how to become a successful businessman (or penguin!), how to travel around on public transport, what the law includes and what the punishments there are for breaking it etc. I also think it’s important to make the prisons hospitable so that he feels like they do care about him because otherwise it might fuel anger and make him want to steal more diamonds. At the same time though, it should not be too nice so that he’ll think that stealing is great, because if you don’t get caught, then you keep whatever you stole and if you do get caught then it doesn’t matter because you will end up staying in a luxury cell with silky soft blankets.

After he is released from prison, I would suggest he would be held under house arrest for 2-3 months. He will live with Wallace and Gromit and he will receive a weekly allowance of £200. With this money, he will spend:

£100 – Feathers will pay Wallace and Gromit rent each week,

£15-he will pay for his own clothes,

£5-phone calls,

£10-public transport,

£35-food,

£5-education,

£15-hygiene,

£15- socialising and misc.

During this time, Feathers could also be home educated in the subjects of Maths, English etc. He should have a schedule so he will learn how to manage his time effectively and eventually should be able to manage his timewithouta schedule. The reason for this is because when Feathers was in prison, he was told what to do every day and at what time he would do it. He now needs to learn how to make those decisions by himself. This would mean when his house arrest is finished, he can go out into the real world and live happy life without breaking the law or stealing. (Linus, 13)

I think that once Feathers McGraw has been captured any money that he has on him will be taken away as well as any disguises that he has and if he still has any belongings left they will be checked to see whether he can have them. After that he should go to a proper prison and not a Zoo, then stay there for 3 months. Once a week, while he is in prison a group of ten penguins will be brought in so that he can be socialised and learn manners and good behaviour from them. However they will be supervised to make sure that they don’t come up with plans to escape. After that he will live with a police officer for 3 years and not leave the house unless a responsible and trustworthy adult accompanies him until he becomes trustworthy himself. He will be taught at the police officers house by a tutor because if he went to school he might run away. Feathers McGraw will have a weekly allowance of £460 that is funded by the government as he won’t have any money. Any money that was taken away from him will be given back in this time. Any money left over will be put into his savings account or used for something else if the money couldn’t quite cover it.

In one week he will give

£60 for fish and food

£10 for travel

£50 for clothing but it will be checked to make sure that it isn’t a disguise.

£80 for the police officer that looking after him

£15 for necessities (tooth brush, tooth paste, face cloth etc…)

£70 for his tutor

£55 for education supplies

£20 will be put in a savings account for when he lives by himself again.

And £100 for some therapy

After 1 year if the police officer looking after him thinks that he’s trustworthy enough then he can get a job and use £40 pounds a week (if he earns manages to earn that much.) as he likes and the rest of it will be put into his savings account. Feathers McGraw will only be allowed to do certain jobs for example, He couldn’t be a police officer in case he steals something that he’s guarding, He also couldn’t be a prison guard in case he helped someone escape etc… If at any point he commits another crime he will lose his freedom and his job and will be confined to the house and garden. When he lives by himself again he will have to do community service for 1 month. (Liv, 11).

Feathers McGraw has committed many crimes, some of which include attempted theft, abuse towards Wallace and Gromit, and prison break.

Here are some ideas of things that we can do to stop him from reoffending:

Immediate action:

A restraining order is to be put in place so he can’t come within 50m of Wallace and Gromit, for their protection both physical and mental. Penguins live for up to 20 years so seeing as he is portrayed as being an adult, my guess is he is around 10 years old. His sentence should be limited to 2 years in prison. Whilst serving his sentence he should be given a laptop (with settings so that he can’t use it to hack) so he can write, watch videos, play games and learn stuff.

Longer term solutions:

When Feathers gets out he will be banned from seeing the gem in museums so there will be less chance of him stelling it. He also will be given some job options to help him get started in his career. His first job won’t be front facing so Wallace and Gromit won’t have to be worried and they will get to say no to any job Feathers tries to get. If he reoffends, he will be taken to court where his sentence will be a minimum of 5 years in prison.

Rehabilitation:

I think Feathers should be given rehabilitation in several different forms, some sneakier than others! One of these forms is probation: penguins which are trained probation officers who will speak to him and try to say that crime is not cool. To him they will look like normal penguins, he won’t know that they have had training. He also should be offered job experience so he can earn a prison currency which he can use to buy upgrades for his cell (for example a better bed, bigger tv, headphones, an mp3 player and songs for said mp3 player) to give him a chance to get a job in the future. (Quinn, 12)

The “crime busters” comments above came after reflecting on our session, their input demonstrates their serious and earnest attempt to resolve an extremely complex issue, which many of the greatest minds in Criminology have battled with for the last two centuries. They may seem very young to deal with a discipline often perceived as dark, but they show us an essential truth about Criminology, it is always hopeful, always focused on what could be, instead of tolerating what we have.

Reflecting on Adolescence

This short series from Netflix has proven to be a national hit, as it rose to be the #1 most streamed programme on the platform in the UK. It has become a popular talking point amongst many viewers, with the programme even reaching into parliament and having praise from the government. After watching it, I can say that it is deserving of its mass popularity, with many aspects welcoming it to my interests.

It is not meant to be an overly dramatised show as we see from other programmes on Netflix. Whilst it fits in the genre of “Drama” it mainly serves itself as a message and portrayal of how toxic masculinity takes form at a young age. One episode was an hour long interrogation that became difficult to watch as it felt as if I was in the room myself, seeing a young boy turn from being vulnerable and scared to intimidating, aggressive and manipulative. As a programme, it does its job of engagement, but its message was displayed even better. Our society has a huge problem with perceptions of masculinity and how young men are growing up in a world that normalises misogyny. The microcosm that Adolescence shows encapsulates this problem well and highlights the problem of the “manosphere” that many young men and even children are turning to as they become radicalised online.

Commentators such as Andrew Tate have become a huge idol to his followers, which are often labelled as “incels”. Sine his rise in popularity in past years, an epidemic of these so called manosphere followers perpetuate misogyny in every corner of their lives, following and believing tales like the “80-20 rule” in which 80% of women are attracted to 20% of men. This kind of mindset is extremely dangerous and, as displayed in Jamie’s behaviour, leads to a feeling of necessity in regard to women liking them. This behaviour isn’t exactly new; it is a form of misogyny that has plagued society for as long as society has been around, however it has been perpetuated further by the “Commentaters”, as I call them.

As a fan of the Silent Hill series, I have always enjoyed stories that dive deep into the psyche and explore wider themes in ways that make the audience uncomfortable, yet willing, to confront. Adolescence does this in the form of a show not so disguised as an overarching message. I feel like it has done its job of making people reflect and critically think about what is wrong with society, and exposing those who do not think about the wider messages and only care about entertainment. I mean, people sit and question whether or not Jamie did the crime and argue that he is not guilty, when the show explicitly shows and tells you what happens through Jamie’s character, demeanour and interactions in the interrogations.

Misogyny and the forces that uphold it are not new concepts and nor will it be an ancient concept any time soon with the way contemporary society functions. Even as society may become more tolerant, there will always be a way for women to be disadvantaged. However, stories like Adolescence may provide a glimmer of hope in dissecting and being a piece of the puzzle that pieces together the wider branches of misogyny and allow for more people to explore its underpinnings.

Global perspectives of crime, state aggression and conflict resolutions

As I prepare for the new academic module “CRI3011 – Global Perspectives of Crime” launching this September, my attention is drawn to the ongoing conflicts in Africa, West Asia and Eastern European nations. Personally, I think these situations provide a compelling case study for examining how power dynamics, territorial aggression, and international law intersect in ways that challenge traditional understandings of crime.

When examining conflicts like those in major Eastern European nations, one begins to see how geopolitical actors strategically frame narratives of aggression and defence. This ongoing conflict represents more than just a territorial dispute in my view, but I think it allows us to see new ways of sovereignty violations, invasions, state misconduct and how ‘humanitarian’ efforts are operationalised. Vincenzo Ruggiero, the renowned Italian criminologist, along with other scholars of international conflict including von Clausewitz, have contributed extensively to this ideology of hostility and aggression perpetrated by state actors, and the need for the criminalisation of wars.

While some media outlets obsess over linguistic choices or the appearance of war leaders not wearing suits, our attention must very much consider micro-aggressions preceding conflicts, the economy of war, the justification of armed interventions (which frequently conceals the intimidation of weaker states), and the precise definition of aggression vs the legal obligation to protect. Of course, I do recognise that some of these characteristics don’t necessarily violate existing laws of armed conflict in obvious ways, however, their impacts on civilian populations must be recognised as one fracturing lives and communities beyond repair.

Currently, as European states are demonstrating solidarity, other regions are engaging in indirect economic hostilities through imposition of tariffs – a form of bloodless yet devastating economic warfare. We are also witnessing a coordinated disinformation campaigns fuelling cross-border animosities, with some states demanding mineral exchange from war-torn nations as preconditions for peace negotiations. The normalisation of domination techniques and a shift toward the hegemony of capital is also becoming more evident – seen in the intimidating behaviours of some government officials and hateful rhetoric on social media platforms – all working together to maintain unequal power imbalance in societies. In fact, fighting parties are now justifying their actions through claims of protecting territorial sovereignty and preventing security threats, interests continue to complicate peace efforts, while lives are being lost. It’s something like ‘my war is more righteous than yours’.

For students entering the global perspectives of crime module, these conflicts offer some lessons about the nature of crime – particularly state crimes. Students might be fascinated to discover how aggression operates on the international stage – how it’s justified, executed, and sometimes evades consequences despite clear violations of human rights and international law. They will learn to question the various ways through which the state can become a perpetrator of the very crimes it claims to prevent and how state criminality often operates in contexts where culpability is contested and consequences are unevenly applied based on power, rather than principle and ethics.

25 years of Criminology

When the world was bracing for a technological winter thanks to the “millennium bug” the University of Northampton was setting up a degree in Criminology. Twenty-five years later and we are reflecting on a quarter of a century. Since then, there have been changes in the discipline, socio-economic changes and wider changes in education and academia.

The world at the beginning of the 21st century in the Western hemisphere was a hopeful one. There were financial targets that indicated a raising level of income at the time and a general feeling of a new golden age. This, of course, was just before a new international chapter with the “war on terror”. Whilst the US and its allies declared the “war on terror” decreeing the “axis of evil”, in Criminology we offered the module “Transnational Crime” talking about the challenges of international justice and victor’s law.

Early in the 21st century it became apparent that individual rights would take centre stage. The political establishment in the UK was leaving behind discussions on class and class struggles and instead focusing on the way people self-identify. This ideological process meant that more Western hemisphere countries started to introduce legal and social mechanisms of equality. In 2004 the UK voted for civil partnerships and in Criminology we were discussing group rights and the criminalisation of otherness in “Outsiders”.

During that time there was a burgeoning of academic and disciplinary reflection on the way people relate to different identities. This started out as a wider debate on uniqueness and social identities. Criminology’s first cousin Sociology has long focused on matters of race and gender in social discourse and of course, Criminology has long explored these social constructions in relation to crime, victimisation and social precipitation. As a way of exploring race and gender and age we offered modules such as “Crime: Perspectives of Race and Gender” and “Youth, Crime and the Media”. Since then we have embraced Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality and embarked on a long journey for Criminology to adopt the term and explore crime trends through an increasingly intersectional lens. Increasingly our modules have included an intersectional perspective, allowing students to consider identities more widely.

The world’s confidence fell apart when in 2008 in the US and the UK financial institutions like banks and other financial companies started collapsing. The boom years were replaced by the bust of the international markets, bringing upheaval, instability and a lot of uncertainty. Austerity became an issue that concerned the world of Criminology. In previous times of financial uncertainty crime spiked and there was an expectation that this will be the same once again. Colleagues like Stephen Box in the past explored the correlation of unemployment to crime. A view that has been contested since. Despite the statistical information about declining crime trends, colleagues like Justin Kotzé question the validity of such decline. Such debates demonstrate the importance of research methods, data and critical analysis as keys to formulating and contextualising a discipline like Criminology. The development of “Applied Criminological Research” and “Doing Research in Criminology” became modular vehicles for those studying Criminology to make the most of it.

During the recession, the reduction of social services and social support, including financial aid to economically vulnerable groups began “to bite”! Criminological discourse started conceptualising the lack of social support as a mechanism for understanding institutional and structural violence. In Criminology modules we started exploring this and other forms of violence. Increasingly we turned our focus to understanding institutional violence and our students began to explore very different forms of criminality which previously they may not have considered. Violence as a mechanism of oppression became part of our curriculum adding to the way Criminology explores social conditions as a driver for criminality and victimisation.

While the world was watching the unfolding of the “Arab Spring” in 2011, people started questioning the way we see and read and interpret news stories. Round about that time in Criminology we wanted to break the “myths on crime” and explore the way we tell crime stories. This is when we introduced “True Crimes and Other Fictions”, as a way of allowing students and staff to explore current affairs through a criminological lens.

Obviously, the way that the uprising in the Arab world took charge made the entire planet participants, whether active or passive, with everyone experiencing a global “bystander effect”. From the comfort of our homes, we observed regimes coming to an end, communities being torn apart and waves of refugees fleeing. These issues made our team to reflect further on the need to address these social conditions. Increasingly, modules became aware of the social commentary which provides up-to-date examples as mechanism for exploring Criminology.

In 2019 announcements began to filter, originally from China, about a new virus that forced people to stay home. A few months later and the entire planet went into lockdown. As the world went into isolation the Criminology team was making plans of virtual delivery and trying to find ways to allow students to conduct research online. The pandemic rendered visible the substantial inequalities present in our everyday lives, in a way that had not been seen before. It also made staff and students reflect upon their own vulnerabilities and the need to create online communities. The dissertation and placement modules also forced us to think about research outside the classroom and more importantly outside the box!

More recently, wars in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia have brought to the forefront many long posed questions about peace and the state of international community. The divides between different geopolitical camps brought back memories of conflicts from the 20th century. Noting that the language used is so old, but continues to evoke familiar divisions of the past, bringing them into the future. In Criminology we continue to explore the skills required to re-imagine the world and to consider how the discipline is going to shape our understanding about crime.

It is interesting to reflect that 25 years ago the world was terrified about technology. A quarter of a century later, the world, whilst embracing the internet, is worriedly debating the emergence of AI, the ethics of using information and the difference between knowledge and communication exchanges. Social media have shifted the focus on traditional news outlets, and increasingly “fake news” is becoming a concern. Criminology as a discipline, has also changed and matured. More focus on intersectional criminological perspectives, race, gender, sexuality mean that cultural differences and social transitions are still significant perspectives in the discipline. Criminology is also exploring new challenges and social concerns that are currently emerging around people’s movements, the future of institutions and the nature of society in a global world.

Whatever the direction taken, Criminology still shines a light on complex social issues and helps to promote very important discussions that are really needed. I can be simply celebratory and raise a glass in celebration of the 25 years and in anticipation of the next 25, but I am going to be more creative and say…

To our students, you are part of a discipline that has a lot to say about the world; to our alumni you are an integral part of the history of this journey. To those who will be joining us in the future, be prepared to explore some interesting content and go on an academic journey that will challenge your perceptions and perspectives. Radical Criminology as a concept emerged post-civil rights movements at the second part of the 20th century. People in the Western hemisphere were embracing social movements trying to challenge the established views and change the world. This is when Criminology went through its adolescence and entered adulthood, setting a tone that is both clear and distinct in the Social Sciences. The embrace of being a critical friend to these institutions sitting on crime and justice, law and order has increasingly become fractious with established institutions of oppression (think of appeals to defund the police and prison abolition, both staples within criminological discourse. The rigour of the discipline has not ceased since, and these radical thoughts have led the way to new forms of critical Criminology which still permeate the disciplinary appeal. In recent discourse we have been talking about radicalisation (which despite what the media may have you believe, can often be a positive impetus for change), so here’s to 25 more years of radical criminological thinking! As a discipline, Criminology is becoming incredibly important in setting the ethical and professional boundaries of the future. And don’t forget in Criminology everyone is welcome!

The Problem with True Crime

There has been a huge spike in interest in true crime in recent years. The introduction to some of the most notorious crimes have been presented on Netflix and other streaming platforms, that has further reinforced the human interest in the gore of violent crimes.

Recently I went to the theatre to watch a show title the Serial Killer Next Door, which highlights some of the most notorious crimes to sweep the nation. From the Toy Box Killer (David Ray-Parker) and his most brutal violence against women to Ed Kemper and the continuous failing by the FBI to bring one of the most violent and prolific killers to justice. While I was horrified by the description both verbal and photographic of the crimes committed, by the serial killers. I was even more shocked at the reaction of the audience and how the cases were presented. The show attempted to sympathise with the victims but this fell short as the entertainment value of the audience was paramount and thus, the presenter honed in on the ‘comedic’ factor of the criminal and the crimes committed. Graphic pictures of the naked bodies of men, women and children brutalised at the hands of the most sadistic monsters were put on screens for speculation and entertainment. Audience members enjoyed popcorn and crisps while lapping up the horror displayed.

I did not stay for the full show…..

The level of distaste was too much for me but from what I did watch made me reflect deeply and led me to the age-old topic among criminologists and victimologists that question where the victims are and why do they continue to be dehumanised. Victims of these heinous crimes are rarely remembered and depicted in a way that moves them away from being viewed as human and instead commodities and after thoughts of crime.

The true crime community on YouTube has been criticized for the sensationalist approach crime. With niche story telling while applying one’s makeup and relaying the most brutal aspects of true crime cases to audiences. I ask the question when and how did we get to this point in society where entertainment trumps victims and their families. Later, this year I will be bringing this topic to a true crime panel to further explore the damage that this type of entertainment has on both the consumer and the victim’s legacy. The dehumanisation of victims and desensitisation of consumers for entertainment tells us something about the society we live in that should be addressed…..I am sure there will be other parts to this post that will explore the issues with true crime and its problematic and exploitative nature.

2024: the year for community and kindness?

The year 2023 was full of pain, loss, suffering, hatred and harm. When looking locally, homelessness and poverty remain very much part of the social fabric in England and Wales, when looking globally, genocide, terror attacks and dictatorships are evident. Politics appear to have lost what little, if any, composure and respect it had: and all in all, the year leaves a somewhat bitter taste in the mouth.

Nevertheless, 2023 was also full of joy, happiness, hope and love. New lives have been welcomed into the world, achievements made, milestones met, communities standing together to march for a ceasefire and to protest against genocide, war, animal rights, global warming and violence against women to name but a few. It is this collective identity I hope punches its way into 2024, because I fear as time moves forward this strength in community, this sense of belonging, appears to be slowly peeling away.

When I recollect my grandparents and parents talking about ‘back in the day’ what stands out most to me is the community identity: the banding together during hard times. The taking an interest, providing a shoulder should it be required. Today, and even if I think back critically over the pandemic, the narrative is very singular: you must stay inside. You must be accountable, you must be responsible, you must get by and manage. There is no narrative of leaning on your neighbours, leaning on your community to the extent that, I’m under the impression, existed before. We have seen and felt this shift very much so within the sphere of criminal justice: it is the individual’s responsibility for their actions, their circumstances and their ‘lot in life’. And the Criminologists amongst you will be uttering expletives at this point. I think what I am attempting to get at, is that for 2024 I would like to see a shared identity as humankind come front and central. For inclusivity, kindness and hope to take flight and not because it benefits us as singular entities, but because it fosters our shared sense of, and commitment to, community.

But ‘community’ exists in so much more than just actions, it is also about our thoughts and beliefs. My worry: whilst kindness and support exist in the world, is that these features only exist if it does not disadvantage (or be perceived to disadvantage) the individual. An example: a person asks me for a sanitary product, and having many of them on me the vast majority of the time, means I am able and happy to accommodate. But what if I only had one left and the likelihood of me needing the last one is pretty high? Do I put myself at a later disadvantage for this person? This person is a stranger: for a friend I wouldn’t even think, I would give it to them. I know I would, and have given out my last sanitary product to strangers who have asked on a number of occasions. And if everyone did this, then once I need a product I can have faith that someone else will be able to support me when required. The issue, in this convoluted way of getting there, is for most of us (including me as evidenced) there is an initial reaction to centralise ‘us’ as an individual rather than focus on the community aspect of it. How will, or even could, this impact me?

Now, I appreciate this is overly generalised, and for those that foster community to all (not just those in their community and are generally very selfless) I apologise. But in 2024, I would like to see people, myself included, act and believe in this sense of community rather than the individualised self. I want people to belong, to support and to generally be kind and not through thinking about how it impacts them to do so. We do not have to be friends with everyone, but just a general level of kindness, understanding and a shared want for a better, inclusive, and safe future would be great!

So Happy New Year to everyone! I hope our 2024 is full of peace, prosperity, community, safety and kindness!

Festive messages, a legendary truce, and some massacres: A Xmas story

Holidays come with context! They bring messages of stories that transcend tight religious or national confines. This is why despite Christmas being a Christian celebration it has universal messages about peace on earth, hope and love to all. Similar messages are shared at different celebrations from other religions which contain similar ecumenical meanings.

The first official Christmas took place on 336 AD when the first Christian Emperor declared an official celebration. At first, a rather small occasion but it soon became the festival of the winter which spread across the Roman empire. All through the centuries more and more customs were added to the celebration and as Europeans “carried” the holiday to other continents it became increasingly an international celebration. Of course, joy and happiness weren’t the only things that brought people together. As this is a Christmas message from a criminological perspective don’t expect it to be too cuddly!

As early as 390 AD, Christmas in Milan was marked with the act of public “repentance” from Emperor Theodosius, after the massacre of Thessalonica. When the emperor got mad they slaughtered the local population, in an act that caused even the repulson of Ambrose, Bishop of Milan to ban him from church until he repented! Considering the volume of people murdered this probably counts as one of those lighter sentences; but for people in power sentences tend to be light regardless of the historical context.

One of those Christmas celebrations that stand out through time, as a symbol of truce, was the 1914 Christmas in the midst of the Great War. The story of how the opposing troops exchanged Christmas messages, songs in some part of the trenches resonated, but has never been repeated. Ironically neither of the High Commands of the opposing sides liked the idea. Perhaps they became concerned that it would become more difficult to kill someone that you have humanised hours before. For example, a similar truce was not observed in World War 2 and in subsequent conflicts, High Commands tend to limit operations on the day, providing some additional access to messages from home, some light entertainment some festive meals, to remind people that there is life beyond war.

A different kind of Christmas was celebrated in Italy in the mid-80s. The Christmas massacre of 1984 Strage Di Natale dominated the news. It was a terrorist attack by the mafia against the judiciary who had tried to purge the organisation. Their response was brutal and a clear indication that they remained defiant. It will take decades before the organisation’s influence diminishes but, on that date, with the death of people they also achieved worldwide condemnation.

A decade later in the 90s there was the Christmas massacre or Masacre de Navidad in Bolivia. On this occasion the government troops decided to murder miners in a rural community, as the mine was sold off to foreign investors, who needed their investment protected. The community continue to carry the marks of these events, whilst the investors simply sold and moved on to their next profitable venture.

In 2008 there was the Christmas massacre in the Democratic Republic of Congo when the Lord’s Resistance Army entered Haut-Uele District. The exact number of those murdered remains unknown and it adds misery to this already beleaguered country with such a long history of suffering, including colonial ethnic cleansing and genocide. This country, like many countries in the world, are relegated into the small columns on the news and are mostly neglected by the international community.

So, why on a festive day that commemorates love, peace and goodwill does one talk about death and destruction? It is because of all those heartfelt notions that we need to look at what really happens. What is the point of saying peace on earth, when Gaza is levelled to the ground? Why offer season’s wishes when troops on either side of the Dnipro River are still fighting a war with no end? How hypocritical is it to say Merry Christmas to those who flee Nagorno Karabakh? What is the point of talking about love when children living in Yemen may never get to feel it? Why go to the trouble of setting up a festive dinner when people in Ethiopia experience famine yet again?

We say words that commemorate a festive season, but do we really mean them? If we did, a call for international truce, protection of the non-combatants, medical attention to the injured and the infirm should be the top priority. The advancement of civilization is not measured by smart phones, talking doorbells and clever televisions. It is measured by the ability of the international community to take a stand and rehabilitate humanity, thus putting people over profit. Sending a message for peace not as a wish but as an urgent action is our outmost priority.

The Criminology Team, wishes all of you personal and international peace!