Home » Cost of Living Crisis

Category Archives: Cost of Living Crisis

What society do we want to live in?

Recently after using a service, I received an email to provide some online feedback. The questionnaire was asking about the services I received and to offer any suggestions on anything that could be done to improve services. This seems to become common practice across the board regarding all types of services and commercial interactions. This got me thinking…we are asked to provide feedback on a recent purchase, but we are not asked about issues that cut through the way we live our lives. In short, there is value in my opinion on a product that I bought, where is the value in my views of how I would want my community to be. Who’s going to ask me what society I want to live in!

Consumerism may be the reason we get asked questions about products but surely before and above being consumers, aren’t we all citizens? I can make helpful suggestions on what I would like to see in services/products but not on government. We profess democratic rule but the application of vote every now and then is not a true reflection on democracy. As we can offer online surveys for virtually everything, we have ways of measuring trends and reactions, why not use these to engage in a wider public discourse on the way to organise our communities, discuss social matters and engage in a public dialogue about our society.

Our political system is constructed to represent parties of different ideologies and practices offering realistic alternatives to governance. An alternative vision about society that people can come behind and support. This ideological diversion is essential for the existence of a “healthy political democratic process”. This ideological difference seems to be less prevalent in public dialogue with the main political parties focusing their rhetoric on matters that do not necessarily affect society.

Activism, a mechanism to bring about social change is becoming a term that sparks controversy whilst special interest groups maintain and even exert their influence on political parties. This allows private special interests to take the “ear of the government” on matters that matter to them, whilst the general public participate in social discourses that never reach the seat of power.

Asking citizens to be part of the social discussion, unlike customer service, is much more significant; it allows us to be part of the process. Those who have no other way of participating in any part of the system will be castigated to cast their vote and may participate in some party political activities. This leaves a whole heap of everyday issues unaddressed. In recent years the cost of living crisis pushed more people into poverty, food, housing and transport became issues that needed attention, not to mention health, post-covid-19.

These and many more social issues have been left either neglected only to be given the overhead title of crisis but with no action plan of how to resolve them. People affected are voiceless, having to pick up the injustices they suffer without any regard to the long term effects. Ironically the only plausible explanation given now that “Brussels’ rule” and “EU bureaucracy” are out of the picture, has become that of the immigrants. The answer to various complex problems became the people on the boats!

This is a simplification in the way social problems happen and most importantly can be resolved. Lack of social discourse has left the explanation and problem solving of said problems to an old rhetoric founded on xenophobia and discrimination. Simple explanations on social problems where the answer is a sentence tend to be very clear and precise, but very rarely can count the complexity of the problems they try to explain. There is a great disservice to our communities to oversimplify causes because the public cannot understand.

Cynically someone may point out that feedback from companies is not routed in an honest request to understand customer satisfaction but a veiled lip-service about company targets and metrics. So the customer’s response becomes a tradable figure of the company’s objectives. This is very likely the case and this is why the process has become so focused on particular parts of the consumer process. Nonetheless and here is the irony; a private company has some knowledge of a customer’s views on their recent purchase, as opposed to the government and people’s views and expectations on many social issues.

Maybe the fault lies with all of us. The presumption of democratic rule, especially in parliamentary democracies, a citizen is represented by a person they elect every four years. This representation detaches the citizen from their own responsibilities and obligations to the process. The State is happy to have citizens that engage only during elections, something that can be underscored by the way in recent years that protests on key social issues have been curtailed.

That does not sound right! I can provide an opinion over the quality of a chocolate bar or a piece of soap but I cannot express my views as a citizen over war, climate, genocide, immigration, human rights or justice? If we value opinion then as society we ought to make space for opinion to be heard, to be articulated and even expressed. In the much published “British Values” the right to protest stands high whilst comes in conflict with new measures to stop any protests. We are at a crossroads and ultimately we will have to decide what kind of society we live in. If we stop protests and we ban venues for people to express themselves, what shall we do next to curtail further the voices of dissent? It is a hackneyed phrase that we are stepping into a “slippery slope” and despite the fact that I do not like the language, there is a danger that we are indeed descending rapidly down that slope.

The social problems our society faces at any given time are real and people try to understand them and come to terms with them. Unlike before, we live in a world that is not just visual, it relies on moving images. Our communities are global and many of the problems we face are international and their impact is likely to affect us all as people, irrespective of background or national/personal identity. At times like this, it is best to increase the public discourse, engage with the voices of descent. Maybe instead of banning protests, open the community to those who are willing to discuss. The fear that certain disruptive people will lead these debates are unfounded. We have been there before and we have seen that people whose agenda is not to engage, but simply to disrupt, soon lose their relevance. We have numerous examples of people that their peers have rejected and history left them behind as a footnote of embarrassment.

Feedback on society, even if negative, is a good place to start when/if anyone wants to consider, what kind of society I want and my family to live in. Giving space to numerous people who have been vastly neglected by the political systems boosts inclusivity and gives everyone the opportunity to be part of our continuous democratic conversation. Political representation in a democracy should give a voice to all especially to those whose voice has long been ignored. Let’s not forget, representation is not a privilege but a necessity in a democracy and we ensure we are making space for others. A democracy can only thrive if we embrace otherness; so when there are loud voices that ask higher level of control and suppression, we got to rise above it and defend the weakest people in our community. Only in solidarity and support of each other is how communities thrive.

LET THEM EAT SOUP

Introduction

What is a can of soup? If you ask a market expert, it is a high-profit item currently pushing £2.30 (branded) in some UK shops[i]. If you ask a historian[ii], it is the very bedrock of organised charity-the cheapest, easiest way to feed a penniless and hungry crowd.

The high price of something so basic, like a £2.30 can of soup, is a massive conundrum when you remember that soup’s main historical job was feeding poor people for almost nothing. Soup, whose name comes from the old word Suppa[iii](meaning broth poured over bread), was chosen by charities because it was cheap, could be made in huge pots, and best of all could be ‘stretched’ with water to feed even more people on a budget[iv].

In 2025, the whole situation is upside down. The price of this simple food has jumped because of “massive economic problems and big company greed[v]. At the same time, the need for charity has exploded with food bank use soaring by an unbelievable 51% compared to 2019[vi]. When basic food is expensive and charity is overwhelmed, it means our country’s safety net is broken.

For those of us who grew up in the chilly North, soup is more than a commodity: it is a core memory. I recall winter afternoons in Yorkshire, scraping frost off the window, knowing a massive pot of soup was bubbling away. Thick, hot and utterly cheap. Our famous carrot and swede soup cost pennies to make, tasted like salvation and could genuinely “fix you.” The modern £2.30 price tag on a can feels like a joke played on that memory, a reminder that the simplest warmth is now reserved for those who can afford the premium.

This piece breaks down some of the reasons why a can of soup costs so much, explores the 250-year-old long, often embarrassing history of soup charity in Britain and shows how the two things-high prices and huge charity demand-feed into a frustrating cycle of managed hunger.

Why Soup Costs £2.30

The UK loves its canned soup: it is a huge business worth hundreds of millions of pounds every year[vii], but despite being a stable market, prices have been battered by outside events.

Remember that huge cost of living squeeze? Food inflation prices peaked at 19.1% in 2023, the biggest rise in 40 years[viii]. Even though things have calmed down slightly, food prices jumped again to 5.1% in August 2025, remaining substantially elevated compared to the overall inflation rate of 3.8% in the same month[ix]. This huge price jump hits basic stuff the hardest, which means that poor people get hurt the most.

Why the drama? A mix of global chaos (like the Ukraine conflict messing up vegetable oil and fertiliser supplies) and local headaches (like the extra costs from Brexit) have made everything more expensive to produce[x].

Here’s the Kicker: Soup ingredients themselves are super cheap. You can make a big pot of vegetable soup at home for about 66p a serving, but a can of the same stuff? £2.30. Even professional caterers can buy bulk powdered soup mix for just 39p per portion[xi].

The biggest chunk of that price has nothing to do with the actual carrots and stock. It’s all the “extras”. You must pay for- the metal can, the flashy label and the marketing team that tries to convince you this soup is a “cosy hug”, and, most importantly everyone’s cut along the way.

Big supermarkets and shops are the main culprits. They need a massive 30-50% profit margin on that can for just putting it on the shelf[xii]. Because people have to buy food to live (you can’t just skip dinner) big companies can grab massive profits, turning something that you desperately need into something that just makes them rich.

This creates the ultimate cruel irony. Historically, soup was accessible because it was simple and cheap. Now, the people who are too busy, too tired or too broke to cook from scratch-the working poor are forced to buy the ready-made cans[xiii]. They end up paying the maximum premium for the convenience they need most, simply because they don’t have the time or space to do it the cheaper way.

How Charity Got Organised

The idea of soup as charity is ancient, but the dedicated “soup kitchen” really took off in late 18th century Britain[xiv].

The biggest reasons were the chaos after the Napoleonic wars and the rise of crowded industrial towns, which meant that lots of people had no money if their work dried up. By 1900 England had gone from a handful of soup kitchens to thousands of them[xv].

The first true soup charity in England was likely La Soupe, started by Huguenot refugees in London in the late 17th Century[xvi]. They served beef soup daily-a real community effort before the phrase “soup kitchen” was even popular.

Soup was chosen as the main charitable weapon because it was incredibly practical. It was cheap, healthy and could be made in enormous quantities. Its real superpower was that it could be “stretched” by adding more water allowing charities to serve huge numbers of people for minimum cost[xvii].

These kitchens were not just about food; they were tools for managing poor people. During the “long nineteenth century” they often fed up to 30% of a local town’s population in winter[xviii]. This aid ran alongside the stern rules of the Old Poor Laws which sorted people into “deserving” (the sick or old) and the ‘undeserving’ (those considered lazy).

The queues, the rules, and the interviews at soup kitchens were a kind of “charity performance” a public way of showing who was giving and who was receiving, all designed to reinforce class differences and tell people how to behave.

The Stigma and Shame of Taking The Soup

Getting a free bowl of soup has always come with a huge dose of shame. It’s basically a public way of telling you “We are the helpful rich people and you are the unfortunate hungry one” Even pictures in old newspapers were designed to make the donors look amazing whilst poor recipients were closely watched[xix].

Early British journalists like Bart Kennedy used to moan about the long, cold queues and how staff would ask “degrading questions” just before you got your soup[xx]. Basically, you had to pass a misery test to get a bowl of watery vegetables, As one 19th Century writer noted, the typical soup house was rarely cleaned, meaning the “aroma of old meals lingers in corners…when the steam from the freshly cooked vegetables brings them back to life”[xxi].

For the recipient, the act of accepting aid became a profound assault on their humanity. The writer George Orwell, captured this degradation starkly, suggesting that a man enduring prolonged hunger “is not a man any longer, only a belly with a few accessory organs”[xxii]. That is the tragic joke here, you are reduced to a stomach that must beg.

By the late 19th Century, people started criticising soup kitchens arguing that they “were blamed for creating the problem they sought to alleviate”[xxiii]. The core problem remains today: giving someone a temporary food handout is just a “band-aid” solution that treats the symptom but ignores the real disease i.e. not enough money to live on.

This critique was affirmed during the Great Depression in Britain, when mobile soup kitchens and dispersal centres became a feature of the British urban landscape[xxiv]. The historical lesson is clear: private charity simply cannot solve a national economic disaster.

The ultimate failure of the system as the historian A.J.P. Taylor pointed out is that the poor demanded dignity. “Soup kitchens were the prelude to revolution, The revolutionaries might talk about socialism, those who actually revolted wanted ‘the right to work’-more capitalism, not it’s abolition[xxv]” They wanted a stable job, not perpetual charity.

Expensive Soup Feeds The Food Bank

The UK poverty crisis means that 7.5 million people (11% of the population) were in homes that did not have enough food in 2023/24[xxvi]. The Trussell Trust alone gave out 2.9 million emergency food parcels in 2024/2025[xxvii]. Crucially, poverty has crept deeper into the workforce: research indicates that three in every ten people referred to in foodbanks in 2024 were from working households[xxviii]. They have jobs but still can’t afford the supermarket prices.

The charities themselves are struggling, hit by a “triple whammy” of rising running costs (energy, rent) and fewer donations[xxix]. This means that many charities have had to cut back, sometimes only giving out three days food instead of a week[xxx]. The safety net in other words is full of holes.

The necessity of navigating poverty systems just to buy food makes people feel trapped and hopeless which is a terrible way to run a country[xxxi].

Modern food banks are still stuck in the old ways of the ‘deserving poor.’ They usually make you get a formal referral—a special voucher—from a professional like a doctor, a Jobcentre person, or the Citizens Advice bureau[xxxii].It’s like getting permission from three different people to have a can of soup.

Charity leaders know this system is broken. The Chief Executive of the Trussell Trust has openly said that food banks are “not the answer” and are just a “fraying sticking plaster[xxxiii].” The system forces a perpetual debate between temporary relief and systemic reform[xxxiv]. The huge growth of private charity, critics argue, just gives the government an excuse to cut back on welfare, pretending that kind volunteers can fix the problem for them[xxxv].

The final, bitter joke links the expensive soup back to the charity meant to fix the cost. Big food companies use inflation to jack up prices and boost profits. Then, they look good by donating their excess stock—often the highly processed, high-profit stuff—to food banks.

This relationship is called the “hunger industrial complex”[xxxvi]. The high-margin, heavily processed canned soup—the quintessential symbol of modern pricing failure—often becomes a core component of the charitable food parcel. The high price charged for the commodity effectively pays for the charity that manages the damage the high price caused[xxxvii]. You could almost call it “Soup-er cyclical capitalism.”

Conclusion

The journey from the 18th-century charitable pot to the 21st-century £2.30 can of soup shows a deep failure in our society. Soup, the hero of cheap hunger relief, has become too pricey for the people who need it most. This cost is driven by profit, not ingredients.

This pricing failure traps poor people in expensive choices, forcing them toward overwhelmed charities. The modern food bank, like the old soup kitchen, acts as a temporary fix that excuses the government from fixing the root cause: low income. As social justice campaigner Bryan Stevenson suggests, “Poverty is the parent of revolution and crime”[xxxviii]. No amount of £2.30 soup can mask the fact that hunger is fundamentally an issue of “justice,” not merely “charity”.

Fixing this means shifting focus entirely. We must stop just managing hunger with charity[xxxix] and instead eliminate the need for charity by making sure everyone has enough money to live and buy their own food. This requires serious changes: regulating the greedy markups on basic food and building a robust state safety net that guarantees a decent income[xl]. The price of the £2.30 can is not just inflation: it’s a receipt for systemic unfairness.

[i]Various Contributors, ‘Reddit Discussion on High Soup Prices’ (Online Forum, 2023) https://www.reddit.com/r/CasualUK/comments/1eooo3o/why_has_soup_gotten_so_expensive

[ii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of Soup Kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790-1914 (PhD Thesis, University of Leicester 2022) https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117?file=37564186

[iii] Soup – etymology, origin & meaning[iii] https://www.etymonline.com/word/soup

[iv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117)

[v] ONS, ‘Food Inflation Data, UK: August 2025’ (Trading Economics Data) https://tradingeconomics.com/united-kingdom/food-inflation

[vi] The Trussell Group-End Of Year Foodbank Stats

https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[vii] GlobalData, ‘Ambient Soup Market Size, Growth and Forecast Analytics, 2023-2028’ (Market Report, 2023) https://www.globaldata.com/store/report/uk-ambient-soup-market-analysis/

[viii] ONS, ‘Consumer Prices Index, UK: August 2025’ (Summary) https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices

[ix] Food Standards Agency, ‘Food System Strategic Assessment’ (March 2023) https://www.food.gov.uk/research/food-system-strategic-assessment-trends-and-issues-impacted-by-uk-economic-condition

[x] Wholesale Soup Mixes (Brakes Foodservice) https://www.brake.co.uk/dry-store/soup/ambient-soup/bulk-soup-mixes

[xii] A Semuels, ‘Why Food Company Profits Make Groceries Expensive’ (Time Magazine, 2023) https://time.com/6269366/food-company-profits-make-groceries-expensive/

[xiii] Christopher B Barrett and others, ‘Poverty Traps’ (NBER Working Paper No. 13828, 2008) https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c13828/c13828.pdf

[xiv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xv] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xvi] The Soup Kitchens of Spitalfields (Blog, 2019) https://spitalfieldslife.com/2019/05/15/the-soup-kitchens-of-spitalfields/

[xvii] Birmingham History Blog, ‘Soup for the Poor’ (2016) https://birminghamhistoryblog.wordpress.com/2016/02/04/soup-for-the-poor/

[xviii] [xviii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xix] Journal Panorama, ‘Feeding the Conscience: Depicting Food Aid in the Popular Press’ (2019) https://journalpanorama.org/article/feeding-the-conscience/

[xx] Journal Panorama, ‘Feeding the Conscience: Depicting Food Aid in the Popular Press’ (2019) https://journalpanorama.org/article/feeding-the-conscience/

[xxi] Joseph Roth, Hotel Savoy (Quote on Soup Kitchens) https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/soup-kitchens

[xxii] Convoy of Hope, (Quotes on Dignity and Poverty) https://convoyofhope.org/articles/poverty-quotes/

[xxiii] Philip J Carstairs, ‘A generous helping? The archaeology of soup kitchens and their role in post-medieval philanthropy 1790–1914’ (Summary, University of Leicester 2022)(https://figshare.le.ac.uk/articles/thesis/A_generous_helping_The_archaeology_of_soup_kitchens_and_their_role_in_post-medieval_philanthropy_1790-1914/21187117

[xxiv] Science Museum Group, ‘Photographs of Poverty and Welfare in 1930s Britain’ (Blog, 2017) https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/photographs-of-poverty-and-welfare-in-1930s-britain/

[xxv] AJ P Taylor, (Quote on Revolution) https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/soup-kitchens

[xxvi] House of Commons Library, ‘Food poverty: Households, food banks and free school meals’ (CBP-9209, 2024) https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9209/

[xxvii] Trussell Trust, ‘Factsheets and Data’ (2024/25) https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[xxviii] The Guardian, ‘Failure to tackle child poverty UK driving discontent’ (2025) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/sep/10/failure-tackle-child-poverty-uk-driving-discontent

[xxix] Charity Link, ‘The cost of living crisis and the impact on UK charities’ (Blog) https://www.charitylink.net/blog/cost-of-living-crisis-impact-uk-charities

[xxxi] The Soup Kitchen (Boynton Beach), ‘History’ https://thesoupkitchen.org/home/history/

[xxxii] Transforming Society, ‘4 uncomfortable realities of food charity’ (Blog, 2023) https://www.transformingsociety.co.uk/2023/12/01/4-uncomfortable-realities-of-food-charity-power-religion-race-and-cash

[xxxiii] The Trussell Group-End Of Year Foodbank Stats

https://www.trussell.org.uk/news-and-research/latest-stats/end-of-year-stats

[xxxiv] The Guardian, ‘Food banks are not the answer’ (2023) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/jun/29/food-banks-are-not-the-answer-charities-search-for-new-way-to-help-uk-families

[xxxv] The Guardian, ‘Britain’s hunger and malnutrition crisis demands structural solutions’ (2023) https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/commentisfree/2023/dec/27/britain-hunger-malnutrition->

[xxxvi] Jacques Diouf, (Quote on Hunger and Justice, 2007) https://www.hungerhike.org/quotes-about-hunger/

[xxxvii] Borgen Magazine, ‘Hunger Awareness Quotes’ (2024) https://www.borgenmagazine.com/hunger-awareness-quotes/

[xxxviii] he Guardian, ‘Failure to tackle child poverty UK driving discontent’ (2025) https://www.theguardian.com/society/2025/sep/10/failure-tackle-child-poverty-uk-driving-discontent

[xxxix] Charities Aid Foundation, ‘Cost of living: Charity donations can’t keep up with rising costs and demand’ (Press Release, 2023) https://www.cafonline.org/home/about-us/press-office/cost-of-living-charity-donations-can-t-keep-up-with-rising-costs-and-demand

[xl] The “Hunger Industrial Complex” and Public Health Policy (Journal Article, 2022) https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9437921/

Cost of Living Crisis: Don’t worry it’s the Sovereign’s Birthday!*

On Saturday 31st May 2025, on Wellington Arch there was an increased presence of police. It was a sunny, albeit windy day in central London, and lots of people (tourists and locals) raised questions around why there appeared to be an increased police presence on this final Saturday of the May half term. At around 1pm approximately, what appeared to be hundreds of uniformed royal officers on horseback paraded through Wellington Arch into Hyde Park. They appeared to have come from Buckingham Palace. It was quite a sight to see! Every Sunday, there is a small parade, known as Changing of the Guard, but this was a substantially bigger ordeal. There is usually 2/3 police bikes that escorts the parade on the Sunday but not the numbers of Police (vans, bikes and officers) out on this sunny Saturday. It is over quickly, but the amount of people power, and I would imagine money, this has used seems quite ridiculous.

It turns out the large parade on May 31st was a ‘practice run’ for the Trooping of the Colour, which will occur on Saturday 15th June 2025. The Trooping of the Colour marks the ‘official’ birthday of the British Soverign and has done so for over 260years (Royal Household, 2025). It involves “Over 1400 parading soldiers, 200 horses and 400 musicians […] in a great display of military precision, horsemanship and fanfare to mark the Sovereign’s official birthday” (Royal Household, 2025). Having seen this every year, it is quite a spectacle and it does generate a buzz and increase in tourism to the area every year. I know the local small businesses in the surrounding areas are grateful for the increase in people, and it draws tourists in globally to view which generates money for the economy. But given the poverty levels visibly evident in London (not to mention those which are hidden), is this a suitable spend of money? Add on the more alarming issues with the monarchy and what it represents steeped in the clutches of empire and fostering hierarchies and inequalities, should this ‘celebration’ still be occurring? It’s the ‘Official’ Birthday of the Sovereign, but how many Birthdays does one need?

According to a Freedom of Information Request, the Ministry of Defence claimed in 2021, the Trooping of the Colour cost taxpayers around £60,000 (not the cost of the event, as there would have been other monies attached to funding this). Imagine what good this money could do: the people it could feed, the people it could provide shelter for, the medical treatment or research it could fund! Given this was 2021, I am going to hazard a guess that in 2025 this is going to cost significantly more. And for what? The Monarchy is the visual embodiment of empire, and according to the National Centre of Social Research, support for and interest in the Monarchy has been steadily declining for the past decade (NCSR, 2025). So even if people choose to ignore the horrific past of the British Sovereigns, it would appear that many are not interested in the Monarchy, regardless of its history (NCSR, 2025). I am aware the Royal family, and these ‘celebrations’, bring in income and generates global interest which translates to the argument that having a Monarchy is ‘economically viable’, but when you look at the disadvantage elsewhere, especially in London, its hard not to question clinging on to such traditions and the expense of meeting people’s basic needs. There is no critical consideration of what maintaining these traditions might suggest, or how they might impact those most effected by the British Empire and Colonialism. So why are these ‘celebrations’ persisting, and why are they having a practice run when steps away from them, in the underpass by Hyde Park Tube station there are people sleeping rough and begging for food? It feels as though there is a serious disconnect between what society needs (affordable homes, food, reasonable living wage, rehabilitation programmes, support and care) and what society will get (a glorified Birthday party for the ‘British Sovereign’).

*Note: the title of the blog should be read dripping in sarcasm.

References:

The National Centre for Social Research (2024) British Social Attitudes: Support for the Monarchy Falls [online]. Available at: https://natcen.ac.uk/news/british-social-attitudes-support-monarchy-falls-new-low [Accessed 4th June 2025].

The Royal Household (2025) What is Trooping the Colour? [Online]. Available at: https://www.royal.uk/what-is-trooping-the-colour#:~:text=The%20Trooping%20of%20the%20Colour,mark%20the%20Sovereign’s%20official%20birthday [Accessed 4th June 2025].

Extortionate Concert Tickets and the Cost of Access

In the realm of live music, few things can compare to the amazing feeling of a packed venue, a beloved band, and the shared energy of thousands of fans singing in unison. But for many, especially those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, this dream remains frustratingly out of reach not due to lack of passion, but because of skyrocketing ticket prices driven by monopolized ticketing systems. Using the example of the band Oasis and their upcoming tour.

The recent announcement of Oasis’ long-awaited reunion concerts sent shockwaves through the music world; particularly for fans who have waited over a decade to hear some of their classic songs sung live again. The excitement was quickly tempered by the reality of ticket prices and the process of getting tickets. Standard Oasis tickets before any premium charges were reportedly being resold for upwards of £300, with official prices starting around £75. For a band rooted in working-class Manchester, the irony is stark: the people who Oasis originally resonated with most are now priced out of seeing them live. Oasis is just an example of this, this can be seen with many different artists globally, and it raises a question of should something be done, and if so, who needs to make the first step and what should that first step be?

At the heart of this issue are ticketing giants who dominate the live event landscape. These companies often employ dynamic pricing models similar to airline pricing where ticket prices fluctuate based on demand. In theory, this aims to reflect market value. In practice, it frequently drives up costs to exploit fan enthusiasm, creating a system that prioritizes profit over accessibility. Worse still, these companies allow and often profit from reselling schemes that further inflate prices. It is only recently where some sites have now put procedures in place for tickets to be resold at the same value to which they were purchased. Additionally, there is the issue of bots buying hundreds of tickets during presales then relisting them on other sites for extortionate prices.

Now to put it into perspective, are there more pressing issues globally that need to be addressed, the answer is yes. However, in the world of criminology where we are constantly thinking about harm, what should be a crime or criminalised, it poses an interesting question and debate. The consequences are significant, particularly for lower-income individuals. Live music, once a unifying and accessible cultural experience, has become a luxury. For a working-class fan, spending £300 on a single concert excluding travel, accommodation, and other costs is unlikely. Add to this the current economic constraints they may be facing elsewhere, and it makes it even more unlikely.

In a world where there are so many pressures, restrictions, worries and concerns, music can be a form of escape and enjoyment. So, should ticket companies be held more accountable? Should there be stronger regulations to prevent price gouging and limit resale abuses? Governments could enforce price caps, mandate transparent pricing structures, or require a certain percentage of tickets to be sold at accessible prices. Additionally, artists themselves may have a role to play; by partnering with ethical ticket vendors or pushing for more equitable ticket distribution. I managed to get tickets at face value price after trying for the third time recently, this was through a process of receiving a unique code via email as a result of being identified as one of the many who had failed on previous occasions. In this sense, I may be classed as one of the lucky ones.

Oasis, a band that once embodied the voice of working-class Britain, now symbolizes a broader issue: the commercialisation of joy. Music should transcend economic boundaries rather than reinforcing them.

Will Santa Visit?

For me Christmas always acts as a stark reminder of inequity, both past and present. I tend to remember television and music, stories of inequity between the haves and the have nots at Christmas time being told by the privileged few. Such as the Muppets Christmas Carol’s (1992) depiction of Tiny Tim, as being poor and disabled but ever so grateful for what he had. Quite recently I was doing some food shopping when I heard the Band Aid (1984) song, Do they know it’s Christmas playing on the tannoy. Despite the criticism relating to white privileged saviorism apparently still this song is popular enough to have a revival in 2024.

Christmas things cost money. So the differences between Christmas experiences of the haves and the have nots are drastic. Whilst many children are very aware that it is Christmas they might also be very aware of the financial constraints that their parents and/or guardians may be in. On the flip side there are other children who will have presents galore and are able to enjoy the festivities that Christmas bring.

This is also a time where goods are advertised and sold that are not needed and not recommended by healthcare professionals. Such as the sale of children’s toys that are dangerous for young children. For example, I was considering purchasing Water Beads as a fun crafting gift option for some children this year, until I was made aware that a children’s hospital and local playgroup are warning parents of the dangers of these as if swallowed can drastically expand in the body which could cause serious health complications.

It seems that social media also adds to the idea that parents and/or guardians should be providing more to enhance the Christmas experience. With posts about creating North Pole breakfasts, Christmas Eve boxes, matching Christmas family Christmas pajamas and expensive Santa visits. All of which come at a financial cost.

As well as this some toys that seem to be trending this year might be seen to misappropriate working class culture. For example, if your parents can afford to take you to Selfridges you can get a ‘fish and chip’ experience when buying Jelly Cat soft toys in the forms of items traditionally purchased from a fish and chip shop (see image above). This experience plus a bundle of these fish chips and peas soft toys cost £130 according to the Jelly Cat website. The profits gained for the Jelly Cat owners are currently being quoted in the news as being £58 million. Whilst at the same time some customers of these real life fish and shops will find it difficult to afford to buy a bag of chips. And some real life fish and chip businesses seem to be at risk of closure, in part due to high cost of living climate which impacts on cost of produce and bills.

Given the above issues it is not surprising that some children are worried that Santa won’t visit them this year.

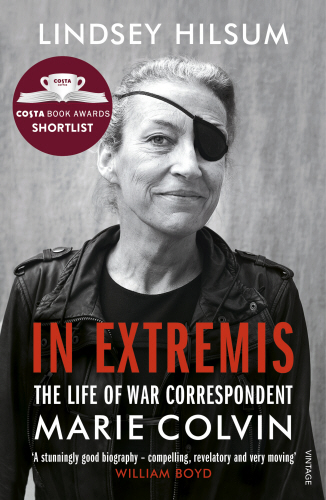

A review of In-Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin

Recently, I picked up a book on the biography of Marie Colvin, a war correspondent who was assassinated in Syria, 2012. Usually, I refrain from reading biographies, as I consider many to be superficial accounts of people’s experiences that are typically removed from wider social issues serving no purpose besides enabling what Zizek would call a fetishist disavowal. It is the biographies of sports players and singers, found on the top shelves of Waterstones and Asda that spring to mind. In-Extremis, however, was different. I consider this book to be a very poignant and captivating biography of war correspondent Marie Colvin, authored by fellow journalist Lindsey Hilsum. The book narrates Marie’s life before her assassination. Her early years, career ventures, intimate relationships, friendships, and relationships with drugs and alcohol were all discussed. So too were the accounts of Marie’s fearless reporting from some of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones, including Sri-Lanka, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. Hilsum wrote on the events both before Marie’s exhilarating career and during the peak of her war correspondence to illustrate the complexities in her life. This reflected on Marie’s insatiability of desire to tell the truth and capture the voices of those who are absent from the ‘script’. So too, reporting on the emotions behind war and conflict in addition to the consistent acts of personal sacrifice made in the name of Justice for the disenfranchised and the voiceless.

Across the first few chapters, Hilsum wrote on the personal life of Marie- particularly her traits of bravery, resilience, persistence, and an undying quest for the truth. Hilsum further delved into the complexities of Marie’s personality and life philosophies. A regular smoker, drinker and partygoer with a captivating personality that drew people in were core to who Marie was according to Hilsum. However, the psychological toils of war reporting became clear, particularly as later in the book, the effects of Marie’s PTSD and trauma began to present itself, particularly after Marie lost eyesight in her left eye after being shot in Sri-Lanka. The eye-patch worn by Marie to me symbolised the way she carried the burdens of her profession and personal vulnerabilities, particularly between maintaining her family life and navigating her occupational hazards.

In writing this biography, Hilsum not only mapped the life of one genuinely awesome and inspiring woman, but also highlighted the importance of reporting and capturing the voices of the casualties of war. Much of her work, I felt resonated with my own. As an academic researcher, it is my job to research on real-life issues and to seek the truth. I resonated with Marie’s quest for the truth and strongly aligned myself to her principles on capturing the lived experiences of those impacted by war, conflict, and social justice issues. These people, I consider are more qualified to discuss these issues than those of us who sit in the ivory towers of institutions (me included!).

Moreover, I considered how I can be more like Marie and how I can embed her philosophies more so into my own research… whether that’s through researching with communities on the cost-of-living crisis or disseminating my research to students, fellow academics, policymakers, and practitioners. I feel inspired and moving forward, I seek to embody the life and spirit of Marie and thousands of other journalists and academics who work tirelessly to research on and understand the truth to bring forward the narratives of those who are left behind and discarded by society in its mainstream.

Uncertainties…

Sallek Yaks Musa

Who could have imagined that, after finishing in the top three, James Cleverly – a frontrunner with considerable support – would be eliminated from the Conservative Party’s leadership race? Or that a global pandemic would emerge, profoundly impacting the course of human history? Indeed, one constant in our ever-changing world is the element of uncertainty.

Image credit: Getty images

The COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in late 2019, serves as a stark reminder of our world’s interconnectedness and the fragility of its systems. When the virus first appeared, few could have foreseen its devastating global impact. In a matter of months, it had spread across continents, paralyzing economies, overwhelming healthcare systems, and transforming daily life for billions. The following 18 months were marked by unprecedented global disruption. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and social distancing became the new norms, forcing us to rethink how we live, work, and interact.

The economic fallout was equally staggering. Supply chains crumbled, unemployment surged, and entire industries teetered on the brink of collapse. Education was upended as schools and universities hastily shifted online, exposing the limitations of existing digital infrastructure. Yet, amid the chaos, communities displayed remarkable resilience and adaptability, demonstrating the need for flexibility in the face of uncertainty.

Beyond health crises, the ongoing climate and environmental emergencies continue to fuel global instability. Floods, droughts, erratic weather patterns, and hurricanes such as Helene and Milton not only disrupt daily life but also serve as reminders that, despite advances in meteorology, no amount of preparedness can fully shield us from the overwhelming forces of nature.

For millions, however, uncertainty isn’t just a concept; it’s a constant reality. The freedom to choose, the right to live peacefully, and the ability to build a future are luxuries for those living under the perpetual threat of violence and conflict. Whether in the Middle East, Ukraine, or regions of Africa, where state and non-state actors perpetuate violence, people are forced to live day by day, confronted with life-threatening uncertainties.

On a more optimistic note, some argue that uncertainty fosters innovation, creativity, and opportunity. However, for those facing existential crises, innovation is a distant luxury. While uncertainty may present opportunities for some, for others, it can be a path to destruction. Life often leaves little room for choice, but when faced with uncertainty, we must make decisions – some minor, others, life-altering. Nonetheless, I am encouraged that while we may not control the future, we must navigate it as best we can, and lead our lives with the thought and awareness that, no one knows tomorrow.

‘A de-construction of the term ‘Cost of Living Crisis’ in recognition of globalism’

The term ‘Cost of Living Crisis’ gets thrown around a lot within everyday discussion, often with little reference to what it means to live under a Cost-of-Living Crisis and how such a crisis is constituted and compares with crises globally. In this blog, I will unpack these questions.

The 2008 Global Financial Crash served as a moment of rupture caused and exacerbated by a series of mini events that unfolded on the world stage…. This partly led to the rise in an annual deficit impacting national growth and debt recovery. Then we entered 2010 when the Coalition Government led by David Cameron and Nick Clegg in the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties implemented a Big Society Agenda, underpinned by an anti-statist ideology and Austerity politics. The legacies of austerity have extensively been highlighted in my own research as communities faced severed cutbacks to social infrastructure and resources, many of whom utilised these resources as a lifeline. Moving forward to the present day in 2024, austerity continues to be alive and well and the national debt has continued to rise…. Events including the Corona Virus Pandemic that started in 2019, Brexit and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have amongst other events served as precipitators to an already existing economic downturn. The rise of interest rates and inflation have been partly led by disruptions to global supply chains, particularly essential and often taken for granted food resources such as wheat and grains. So too has political instability hindering opportunities to invest and grow the local economy contributed towards this economic downturn.

As inflation and interest rates rose, so too did the average cost of living in terms of expenditure and disposable income for both the Working and Middle-Classes. At this point, one can begin to see the emergence of the cost-of-living crisis as being constituted as an issue affecting social class.

The cost-of-living crisis is inherently a term deployed by the Middle Classes as some faced an increase of interest rates on their mortgages in addition to rising costs in the supermarkets. These are valid concerns and the reality and hardship produced under these conditions is not being contested. However, we must not lose sight of the fact that economic downturn and the reality of poverty is nothing new for many working-class communities, who have suffered from disinvestment and austerity, long before the term Cost of Living Crisis came into being.

Equally, we can understand the Cost-of-Living Crisis as being a construction led by Western states, as part of a wider Global North. The separation between the Global North and Global South is bound by geography, but economic growth and its globally recognised position as an emerged or emerging economy. Note that such constructions within themselves are applied by the Global North. Similarly, the Cost-of-Living Crisis is nothing new for these states. The reality of living below a breadline is faced by many of these countries in the Global South and should be understood as a wider systemic and global issue that members of the International Community have a moral obligation to address.

So, when applying terms such as the Cost-of-Living Crisis under every-day discussion, it is necessary to contemplate the historicisms behind such an experience and how life under poverty and hardship is experienced globally and indeed across our own communities. This will enable us to think more critically about this term Cost of Living Crisis, which as it is widely used, faces threat of oversight as to the prevalence and effects of global and local inequalities.

Meet the Team: Liam Miles, Lecturer in Criminology

Hello!

I am Liam Miles, a lecturer in criminology and I am delighted to be joining the teaching team here at Northampton. I am nearing the end of my PhD journey that I completed at Birmingham City University that explored how young people who live in Birmingham are affected by the Cost-of-Living Crisis. I conducted an ethnographic study and spent extensive time at two Birmingham based youth centres. As such, my research interests are diverse and broad. I hold research experience and aspirations in areas of youth and youth crime, cost of living and wider political economy. This is infused with criminological and social theory and qualitative research methods. I am always happy to have a coffee and a chat with any student and colleague who wishes to discuss such topics.

Alongside my PhD, I have completed two solo publications. The first is a journal article in the Sage Journal of Consumer Culture that explored how violent crime that occurs on British University Campuses can be explained through the lens of the Deviant Leisure perspective. An emerging theoretical framework, the Deviant Leisure perspective explores how social harms are perpetuated under the logics and entrenchment of free-market globalised capitalism and neoliberalism. As such, a fundamental source of culpability towards crime, violence and social harm more broadly is located within the logics of neoliberal capitalism under which a consumer culture has arisen and re-cultivated human subjectivity towards what is commonly discussed in the literature as a narcissistic and competitive individualism. My second publication was in an edited book titled Action on Poverty in the UK: Towards Sustainable Development. My chapter is titled ‘Communities of Rupture, Insecurity, and Risk: Inevitable and Necessary for Meaningful Political Change?’. My chapter explored how socio-political and economic moments of rupture to the status quo are necessary for the summoning of political activism; lobbying and subsequent change.

It is my intention to maintain a presence in the publishing field and to work collaboratively with colleagues to address issues of criminal and social justice as they present themselves. Through this, my focus is on a lens of political economy and historical materialism through which to make sense of local and global events as they unfold. I welcome conversation and collaboration with colleagues who are interested in these areas.

Equally, I am committed to expanding my knowledge basis and learning about the vital work undertaken by colleagues across a breadth of subject areas, where it is hoped we can learn from one another.

I am thoroughly looking forward to meeting everyone and getting to learn more!

Is the cost of living crisis just state inflicted violence

Back in November 2022, social media influencer Lydia Millen was seen to spark controversy on the popular app ‘TikTok’ when she claimed that her heating was broken, so she therefore was going to check into the Savoy in London.

Her video, which she filmed whilst wearing an outfit worth over £30,000, sparked outrage on the app and across popular social media platforms. People began to argue that her comment was not well received in our current social climate, where people have to choose whether they should spend money on heating or groceries. For many, no matter your financial situation, problems with heating rarely resorts in a luxury stay in London.

With pressure mounting, Lydia decided to reply to comments on her video. When one individual stated “My heating is off because I can’t afford to put it on”, Lydia replied “It’s honestly heart breaking I just hope you know that other people’s realities can be different and that’s not wrong”. Sorry, Lydia; it is wrong. Realities are not different; they are miles apart. This is clearly seen in the fact that the National Institute of Economic and Social Research estimate that 1.5 million households in the UK over the next year will be landed in poverty (NIESR, 2022).

Ultimately, this is a social issue. Like Lydia said, in a society in which individuals are stratified based on their economic, cultural and social capital, we are conditioned to believe that this is just the way it is, and therefore, it is not wrong that other people have different realities. However, for me, it is not ‘different realities’, it is a matter of being able to eat and be warm versus being able to stay in a luxury hotel in London.

So, why is this a criminological issue? The cost of living crisis is simply just state inflicted poverty. Alike to Lydia with her social following, the government have the power to make change and use their position in society to remedy cost of living issues, but they don’t. This is not a mark of their failure as a government, it is a mark of their success. You only have to look at the government’s complete denial surrounding social issues to realise that this was their plan all along, and the longer this denial continues, the longer they succeed. This is seen in the case of Lydia Millen, who has acted as a metaphor for the level of negligence in which the government exercises over its citizens. Ultimately, for Lydia, it is very easy to tuck yourself into a luxury bed in the Savoy and close the curtains on the real world. The people affected by the crisis are not people like Lydia Millen, they are everyday people who work 40+ hours a week, and still cannot make ends meet. For the government, the cost of living crisis is the perfect way to separate the wheat from the chaff.

Ultimately, the cost of living crisis is not too dissimilar to the strikes that the UK is currently experiencing. Alike to the strikes, the cost of living crisis was always going to happen at the hands of a negligent government. The only way we can begin to address this problem is by giving our support, by supporting strikes all across the country, and by standing up for what is right. After all, the powers in our country have shown that our needs as a society are not a priority, so it is time to support ourselves.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” ― Martin Luther King Jr.

References:

National Institute of Economic and Social Research (2022) What Can Be Done About the Cost-of-Living Crisis? NIESR [online]. Available from: https://www.niesr.ac.uk/blog/what-can-be-done-about-the-cost-of-living-crisis [Accessed 23/01/23].