Home » Conflict

Category Archives: Conflict

Global perspectives of crime, state aggression and conflict resolutions

As I prepare for the new academic module “CRI3011 – Global Perspectives of Crime” launching this September, my attention is drawn to the ongoing conflicts in Africa, West Asia and Eastern European nations. Personally, I think these situations provide a compelling case study for examining how power dynamics, territorial aggression, and international law intersect in ways that challenge traditional understandings of crime.

When examining conflicts like those in major Eastern European nations, one begins to see how geopolitical actors strategically frame narratives of aggression and defence. This ongoing conflict represents more than just a territorial dispute in my view, but I think it allows us to see new ways of sovereignty violations, invasions, state misconduct and how ‘humanitarian’ efforts are operationalised. Vincenzo Ruggiero, the renowned Italian criminologist, along with other scholars of international conflict including von Clausewitz, have contributed extensively to this ideology of hostility and aggression perpetrated by state actors, and the need for the criminalisation of wars.

While some media outlets obsess over linguistic choices or the appearance of war leaders not wearing suits, our attention must very much consider micro-aggressions preceding conflicts, the economy of war, the justification of armed interventions (which frequently conceals the intimidation of weaker states), and the precise definition of aggression vs the legal obligation to protect. Of course, I do recognise that some of these characteristics don’t necessarily violate existing laws of armed conflict in obvious ways, however, their impacts on civilian populations must be recognised as one fracturing lives and communities beyond repair.

Currently, as European states are demonstrating solidarity, other regions are engaging in indirect economic hostilities through imposition of tariffs – a form of bloodless yet devastating economic warfare. We are also witnessing a coordinated disinformation campaigns fuelling cross-border animosities, with some states demanding mineral exchange from war-torn nations as preconditions for peace negotiations. The normalisation of domination techniques and a shift toward the hegemony of capital is also becoming more evident – seen in the intimidating behaviours of some government officials and hateful rhetoric on social media platforms – all working together to maintain unequal power imbalance in societies. In fact, fighting parties are now justifying their actions through claims of protecting territorial sovereignty and preventing security threats, interests continue to complicate peace efforts, while lives are being lost. It’s something like ‘my war is more righteous than yours’.

For students entering the global perspectives of crime module, these conflicts offer some lessons about the nature of crime – particularly state crimes. Students might be fascinated to discover how aggression operates on the international stage – how it’s justified, executed, and sometimes evades consequences despite clear violations of human rights and international law. They will learn to question the various ways through which the state can become a perpetrator of the very crimes it claims to prevent and how state criminality often operates in contexts where culpability is contested and consequences are unevenly applied based on power, rather than principle and ethics.

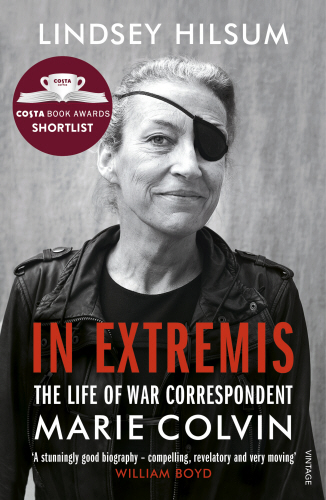

A review of In-Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin

Recently, I picked up a book on the biography of Marie Colvin, a war correspondent who was assassinated in Syria, 2012. Usually, I refrain from reading biographies, as I consider many to be superficial accounts of people’s experiences that are typically removed from wider social issues serving no purpose besides enabling what Zizek would call a fetishist disavowal. It is the biographies of sports players and singers, found on the top shelves of Waterstones and Asda that spring to mind. In-Extremis, however, was different. I consider this book to be a very poignant and captivating biography of war correspondent Marie Colvin, authored by fellow journalist Lindsey Hilsum. The book narrates Marie’s life before her assassination. Her early years, career ventures, intimate relationships, friendships, and relationships with drugs and alcohol were all discussed. So too were the accounts of Marie’s fearless reporting from some of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones, including Sri-Lanka, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. Hilsum wrote on the events both before Marie’s exhilarating career and during the peak of her war correspondence to illustrate the complexities in her life. This reflected on Marie’s insatiability of desire to tell the truth and capture the voices of those who are absent from the ‘script’. So too, reporting on the emotions behind war and conflict in addition to the consistent acts of personal sacrifice made in the name of Justice for the disenfranchised and the voiceless.

Across the first few chapters, Hilsum wrote on the personal life of Marie- particularly her traits of bravery, resilience, persistence, and an undying quest for the truth. Hilsum further delved into the complexities of Marie’s personality and life philosophies. A regular smoker, drinker and partygoer with a captivating personality that drew people in were core to who Marie was according to Hilsum. However, the psychological toils of war reporting became clear, particularly as later in the book, the effects of Marie’s PTSD and trauma began to present itself, particularly after Marie lost eyesight in her left eye after being shot in Sri-Lanka. The eye-patch worn by Marie to me symbolised the way she carried the burdens of her profession and personal vulnerabilities, particularly between maintaining her family life and navigating her occupational hazards.

In writing this biography, Hilsum not only mapped the life of one genuinely awesome and inspiring woman, but also highlighted the importance of reporting and capturing the voices of the casualties of war. Much of her work, I felt resonated with my own. As an academic researcher, it is my job to research on real-life issues and to seek the truth. I resonated with Marie’s quest for the truth and strongly aligned myself to her principles on capturing the lived experiences of those impacted by war, conflict, and social justice issues. These people, I consider are more qualified to discuss these issues than those of us who sit in the ivory towers of institutions (me included!).

Moreover, I considered how I can be more like Marie and how I can embed her philosophies more so into my own research… whether that’s through researching with communities on the cost-of-living crisis or disseminating my research to students, fellow academics, policymakers, and practitioners. I feel inspired and moving forward, I seek to embody the life and spirit of Marie and thousands of other journalists and academics who work tirelessly to research on and understand the truth to bring forward the narratives of those who are left behind and discarded by society in its mainstream.

Let us not forget

Yesterday marked the 80th anniversary of the D Day landings and it has seen significant coverage from the media as veterans, families, dignitaries, and others converge on the beaches and nearby towns in France. If you have watched the news coverage during the week, you will have seen interviews with the veterans involved in those landings. What struck me about those interviews was the humbleness of those involved, they don’t consider themselves heroes but reserve that word for those that died. For most of us, war is something that happens elsewhere, and we can only glimpse the horrors of war in our imaginations. For some though, it is only too real, and for some, it is a reality now.

I was struck by some of the conversations. Imagine being on ship, sailing across the English Channel and looking back at the white cliffs of Dover and being told by someone in charge, ‘have a good look because a lot of you will never see them again’. If knowing that you are going to war was not bad enough, that was a stark reminder that war means a high chance of death. And most of those men going over to France were young, to put it in perspective, the age of our university students. If you watched the news, you will have seen the war cemeteries with rows upon rows, upon rows of headstones, each a grave of someone whose life was cut short. Of course, that only represents a small number of the combatants that died in the war, there are too many graveyards to mention, too many people that died. Too many people both military and civilian that suffered.

The commemoration of the D Day landings and many other such commemorations serve as a reminder of the horrors of war when we have the opportunity to hear the stories of those involved. But as their numbers dwindle, so too does the narrative of the reality, only to be replaced with some romantic notion about glory and death. There is no glory in war, only death, suffering and destruction.

The repeated, ‘never again’ after the first and second world war seems to have been a utopian dream. Whilst we may have been spared the horrors of a world war to this point, we should not forget the conflicts across the world, too numerous to list here. Often, the reasons behind them are difficult to comprehend given the inevitable outcomes. As one veteran on the news pointed out though ‘war is a nonsense, but sometimes it’s necessary’.

The second part of that is a difficult sentiment to swallow but then, if your country faces invasion, your people face being driven from their homes or into slavery or worse, then choices become very stark. We should be grateful to those people that fought for our freedoms that we enjoy now. We should remember that there are people doing the same across the world for their own freedoms and perhaps vicariously ours. And perhaps, we should look to ourselves and think about our tolerance for others. Let us not forget, war is a nonsense, and there is no glory in it, only death and destruction.

Liberalism, Capitalism and Broken Promises

With international conflict rife, imperialism alive and well and global and domestic inequalities broadening, where are the benefits that the international liberal order promised?

As part of my masters, I am reading through an interesting textbook named Theories of International Relations (Burchill, 2013). Soon, I’ll have a lecture speaking about liberalism within the realm of international relations (IR). The textbook mentions liberal thought concerning the achievement of peace through processes of democracy and free trade, supposedly, through these mechanisms, humankind can reach a place of ‘perpetual peace’, as suggested by Kant.

Capitalism supposedly has the power to distribute scarce resources to citizens, while liberalist free trade should break down artificial barriers between nations, uniting them towards a common goal of sharing commodities and mitigating tensions by bringing states into the free trade ‘community’. With this, in theory, should bring universal and democratic peace, bought about by the presence of shared interest.

Liberal capitalism has had a long time to prove its worth, with the ideology being adopted by the majority of the west, and often imposed on countries in the global south through coercive trade deals, political interference and the establishment of dependant economies. Evidence of the positives of liberal capitalism, in my opinion are yet to be seen. In fact, the evidence points towards a global and local environment entirely contrary to the claims of liberal capitalism.

The international institutions, constructed to mitigate against the anarchic system we live under become increasingly fragile and powerless. The guarantee of global community and peace seems further and further away. The pledge that liberalism will result in the spread of resources, resulting in the ultimate equalisation is unrealised.

Despite all of this, the global liberal order seems to still be supported by the majority of the elite and by voters alike. Because with the outlined claims comes the promise that one day, with some persistence, patience and hard work, you too could reap the rewards of capitalism just like the few in society do.

Civilian Suffering Beyond the Headlines

In the cacophony of war, amidst the geopolitical chess moves and strategic considerations, it’s all too easy to lose sight of the human faces caught in its relentless grip. The civilians, the innocents, the ordinary people whose lives are shattered by the violence they never asked for. Yet, as history often reminds us, their stories are the ones that linger long after the guns fall silent. In this exploration, we delve into the forgotten narratives of civilian suffering, from the tragic events of Bloody Sunday to the plight of refugees and aid workers in conflict zones like Palestine.

On January 30, 1972, the world watched in horror as British soldiers opened fire on unarmed civil rights demonstrators in Northern Ireland, in what would become known as Bloody Sunday. Fourteen innocent civilians lost their lives that day, and many more were injured physically and emotionally. Yet, as the decades passed, the memory of Bloody Sunday faded from public consciousness, overshadowed by other conflicts and crises. But for those who lost loved ones, the pain and trauma endure, a reminder of the human cost of political turmoil and sectarian strife.

Fast forward to the present day, and we find a world still grappling with the consequences of war and displacement. In the Middle East, millions of Palestinians endure the daily hardships of life under occupation, their voices drowned out by the rhetoric of politicians and the roar of military jets. Yet amid the rubble and despair, there are those who refuse to be silenced, who risk their lives to provide aid and assistance to those in need. These unsung heroes, whether they be doctors treating the wounded or volunteers distributing food and supplies, embody the spirit of solidarity and compassion that transcends borders and boundaries.

But even as we celebrate their courage and resilience, we must also confront our own complicity in perpetuating the cycles of violence and injustice that afflict so many around the world. For every bomb that falls and every bullet that is fired, there are countless civilians who pay the price, their lives forever altered by forces beyond their control. And yet, all too often, their suffering is relegated to the footnotes of history, overshadowed by the grand narratives of power and politics.

So how do we break free from this cycle of forgetting? How do we ensure that the voices of the marginalized and the oppressed are heard, even in the midst of chaos and conflict? Perhaps the answer lies in bearing witness, in refusing to turn away from the harsh realities of war and its aftermath. It requires us to listen to the stories of those who have been silenced, to amplify their voices and demand justice on their behalf.

Moreover, it necessitates a revaluation of our own priorities and prejudices, a recognition that the struggle for peace and justice is not confined to distant shores but is woven into the fabric of our own communities. Whether it’s challenging the narratives of militarism and nationalism or supporting grassroots movements for social change, each of us has a role to play in building a more just and compassionate world.

The forgotten faces of war remind us of the urgent need to confront our collective amnesia and remember the human cost of conflict. From the victims of Bloody Sunday to the refugees fleeing violence and persecution, their stories demand to be heard and their suffering acknowledged. Only then can we hope to break free from the cycle of violence and build a future were peace and justice reigns supreme.

It’s all about me: when did I become invisible?

I wander around on the pavement, earbuds neatly fitted, mobile phone conveniently held in front of me so I can see the person I’m talking to. You can all listen to my conversation whilst attempting to navigate around me, oops, someone bumped into me, a small boy left sprawling, I laugh, not at the small boy, but the joke my mate has just relayed, it’s funny right. People weave left and right but me, I don’t worry, I walk straight on, embroiled in my conversation, it’s not about them, it’s about me.

There’s my friend and his family, let’s stop here, in the middle of the pavement and let’s talk. What, people are having to walk in the road to get past, I’m discussing weighty matters here, can’t you see, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

I hop on the bus, earbuds, I’m not sure where they are. Now where’s that YouTube video my mate told me about, oh yeah, here it is. Now that’s hilarious, can’t hear it because of all the hub bub around me, turn it up and enjoy, I’m having a gas. Didn’t want to listen to that? It’s not about you, it’s about me.

And now at work, I take up the laptop and watch some TED talk video, I need to go somewhere so with laptop open, speaker on full, I wander across the office and out through the door held open for me. I don’t acknowledge your politeness, I don’t see you, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

I sit waiting for a colleague to join me in an open area, people around using laptops, having conversations, I turn the volume up, this video is good, I need to hear it, it’s not about the rest of you, it’s about me.

I go to the work restaurant with my friend, it’s a bit busy, never mind we can sit here. I push my chair back banging into another chair, catching the knuckles of someone that happens to be leaning on the chair. I don’t see it, I don’t see you, I want to sit here right, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

And when I learn to drive, I’m going to speed even if it is dangerous because I will need to get to where I am going quickly, it’s not about the rest of you, it’s about me. And I will be the one that overtakes all the cars in the queue, only to push in at the last moment. My indicator tells you to give me room, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

And when I have kids, I will park right outside the school, never mind if I obstruct the road, I need to pick up my little darlings, it’s not about you, it’s about me.

And in my real world, when I have to constantly move out of the way of people on phones, have to listen to videos and conversations I have no interest in, hold doors open without even a glance from the person that has walked through, have my knuckles scraped with the back of a chair, without even an acknowledgement that something has happened, despite my yelp from the pain, when I sit watching the idiots overtaking and have to brake to avoid a collision as they push into the queue, when I sit and wait in the road whilst someone strolls along, little one in tow and straps them in the back seat before having a quick chat with another parent, I inwardly shout to myself; WHEN WAS IT THAT I BECAME INVISIBLE? I’s not just about you, it’s also about me.

Christmas Toys

In CRI3002 we reflected on the toxic masculine practices which are enacted in everyday life. Hegemonic masculinity promotes the ideology that the most respectable way of being ‘a man’ is to engage in masculine practices that maintain the White elite’s domination of marginalised people and nations. What is interesting is that in a world that continues to be incredibly violent, the toxicity of state-inflicted hegemonic masculinity is rarely mentioned.

The militaristic use of State violence in the form of the brutal destruction of people in the name of apparent ‘just’ conflicts is incredibly masculine. To illustrate, when it is perceived and constructed that a privileged position and nation is under threat, hegemonic masculinity would ensure that violent measures are used to combat this threat.

For some, life is so precious yet for others, life is so easily taken away. Whilst some have engaged in Christmas traditions of spending time with the family, opening presents and eating luxurious foods, some are experiencing horrors that should only ever be read in a dystopian novel.

Through privileged Christmas play-time with new toys like soldiers and weapons, masculine violence continues to be normalised. Whilst for some children, soldiers and weapons have caused them to be victims of wars with the most catastrophic consequences.

Even through children’s play-time the privileged have managed to promote everyday militarism for their own interests of power, money and domination. Those in the Global North are lead to believe that we should be proud of the army and how it protects ‘us’ by dominating ‘them’ (i.e., ‘others/lesser humans and nations’).

Still in 2023 children play with symbolically violent toys whilst not being socialised to question this. The militaristic toys are marketed to be fun and exciting – perhaps promoting apathy rather than empathy. If promoting apathy, how will the world ever change? Surely the privileged should be raising their children to be ashamed of the use of violence rather than be proud of it?

Festive messages, a legendary truce, and some massacres: A Xmas story

Holidays come with context! They bring messages of stories that transcend tight religious or national confines. This is why despite Christmas being a Christian celebration it has universal messages about peace on earth, hope and love to all. Similar messages are shared at different celebrations from other religions which contain similar ecumenical meanings.

The first official Christmas took place on 336 AD when the first Christian Emperor declared an official celebration. At first, a rather small occasion but it soon became the festival of the winter which spread across the Roman empire. All through the centuries more and more customs were added to the celebration and as Europeans “carried” the holiday to other continents it became increasingly an international celebration. Of course, joy and happiness weren’t the only things that brought people together. As this is a Christmas message from a criminological perspective don’t expect it to be too cuddly!

As early as 390 AD, Christmas in Milan was marked with the act of public “repentance” from Emperor Theodosius, after the massacre of Thessalonica. When the emperor got mad they slaughtered the local population, in an act that caused even the repulson of Ambrose, Bishop of Milan to ban him from church until he repented! Considering the volume of people murdered this probably counts as one of those lighter sentences; but for people in power sentences tend to be light regardless of the historical context.

One of those Christmas celebrations that stand out through time, as a symbol of truce, was the 1914 Christmas in the midst of the Great War. The story of how the opposing troops exchanged Christmas messages, songs in some part of the trenches resonated, but has never been repeated. Ironically neither of the High Commands of the opposing sides liked the idea. Perhaps they became concerned that it would become more difficult to kill someone that you have humanised hours before. For example, a similar truce was not observed in World War 2 and in subsequent conflicts, High Commands tend to limit operations on the day, providing some additional access to messages from home, some light entertainment some festive meals, to remind people that there is life beyond war.

A different kind of Christmas was celebrated in Italy in the mid-80s. The Christmas massacre of 1984 Strage Di Natale dominated the news. It was a terrorist attack by the mafia against the judiciary who had tried to purge the organisation. Their response was brutal and a clear indication that they remained defiant. It will take decades before the organisation’s influence diminishes but, on that date, with the death of people they also achieved worldwide condemnation.

A decade later in the 90s there was the Christmas massacre or Masacre de Navidad in Bolivia. On this occasion the government troops decided to murder miners in a rural community, as the mine was sold off to foreign investors, who needed their investment protected. The community continue to carry the marks of these events, whilst the investors simply sold and moved on to their next profitable venture.

In 2008 there was the Christmas massacre in the Democratic Republic of Congo when the Lord’s Resistance Army entered Haut-Uele District. The exact number of those murdered remains unknown and it adds misery to this already beleaguered country with such a long history of suffering, including colonial ethnic cleansing and genocide. This country, like many countries in the world, are relegated into the small columns on the news and are mostly neglected by the international community.

So, why on a festive day that commemorates love, peace and goodwill does one talk about death and destruction? It is because of all those heartfelt notions that we need to look at what really happens. What is the point of saying peace on earth, when Gaza is levelled to the ground? Why offer season’s wishes when troops on either side of the Dnipro River are still fighting a war with no end? How hypocritical is it to say Merry Christmas to those who flee Nagorno Karabakh? What is the point of talking about love when children living in Yemen may never get to feel it? Why go to the trouble of setting up a festive dinner when people in Ethiopia experience famine yet again?

We say words that commemorate a festive season, but do we really mean them? If we did, a call for international truce, protection of the non-combatants, medical attention to the injured and the infirm should be the top priority. The advancement of civilization is not measured by smart phones, talking doorbells and clever televisions. It is measured by the ability of the international community to take a stand and rehabilitate humanity, thus putting people over profit. Sending a message for peace not as a wish but as an urgent action is our outmost priority.

The Criminology Team, wishes all of you personal and international peace!

What value life in a far-off land?

Watching the BBC news and for that matter any other news broadcast has become almost unbearable. Over the last three weeks or so the television screen has been filled with images of violence, grief, and suffering. Images of innocent men, women and children killed or maimed or kidnapped. Images of grieving relatives, images of people with little or no hope. And as I watch I am consumed by overwhelming sadness and as I write this blog, I cannot avoid the tears welling up. And I am angry, angry at those that could perpetuate such crimes against humanity. I will not take sides as I know that I understand so little about the conflict in Israel, Gaza, and the surrounding area, but I do feel the need to comment. It seems to me that there is shared blame across the countries involved, the region, and the rest of the world.

As I watch the news, I see reports of protest across many countries, and I see a worrying development of Islamophobia and Antisemitism. The conflict is only adding fuel to the actions of those driven by hatred and it provides plenty of scope for politicians in the West and other countries, to pontificate, and partake in political wrangling and manoeuvring before showing their abject disregard for morality and humanity. The fact that Hamas, as we are constantly reminded by the BBC, is a proscribed terrorist organisation, proscribed by most countries in the west, including the United Kingdom, seems to give carte blanche to western politicians to support crimes against humanity, to support murder and terrorism. How else can we describe what is going on?

The actions of Hamas should and quite rightly are to be condemned, any action that sees the killing of innocent lives is wrong. To have carried out their recent attacks in Israel in such a manner was horrendous and is a reminder of the dangers that the Israeli people face daily. But the declaration by Israel that it wants to remove Hamas from the face of the earth would, and could, only lead to one outcome, that being played out before our very eyes. The approach seems to be one of vengeance, regardless of the human cost and regardless of any rules of war or conflict or human dignity. How else can the bombing and shelling of a whole country be explained? How else can the blockading of a country to bring it to the brink of disaster be justified? How do we explain the forced migration of innocent people from one part of a country to another only to find that the edict to move led them into as dangerous a place as that they moved from? There seems to be a very sad irony in this, given the historical perspectives of the Israeli nation and its people.

We don’t know what efforts are going on behind the scenes to attempt to bring about peace but the outrageous comments and actions or omissions by some western politicians beggar belief. From Joe Biden’s declaration ‘now is not the time for a ceasefire’ to our government’s and the opposition’s policy that a pause in the conflict should occur, but not a ceasefire, only demonstrates a complete lack of empathy for the plight of Palestinian people. If not now, at what time would it be appropriate for a ceasefire to occur? It seems to me, as a colleague suggested, politicians and many others seem to be more concerned about accusations of antisemitism than they are about humanity. Operating in a moral vacuum seems to be par for the government in the UK and unfortunately that seems to extend to the other side of the house. Just as condemning the killing of innocent people is not Antisemitic nor too are the protests about those killings a hate crime. Our home secretary seems to have nailed her colours to the mast on that one but I’m not sure if its xenophobia, power lust or something else being displayed. Populism and a looming general election seems to be far more important than innocent children’s lives in a far off land.

The following quote seems so apt:

‘…. politicians must shoulder their share of the blame. And individuals too. Those ordinary citizens who allowed themselves to be incited into hatred and religious xenophobia, who set aside decades, sometimes centuries of friendship, who took up sword and flame to terrorise their neighbours and compatriots, to murder men, women, and children in a frenzy of bloodlust that even now is difficult to comprehend (Khan, 2021: 323).’[1]

If you are not angry, you should be, if you do not cry, then I ask why not? This is not the way that humanity should behave, this is humanity at its worst. Just because it is somewhere else, because it involves people of a different race, colour or creed doesn’t make it any less horrendous.

Khan, V. (2021) Midnight at Malabar House, Hodder and Stoughton: London.

[1] Vaseem Khan was discussing Partition on the Indian subcontinent, but it doesn’t seem to matter where the conflict is or what goes on, the reasons for it are so hard to comprehend.

The crime of war

a depiction of Troy

Recently after yet another military campaign coming to an end, social media lit all over with opinions about what should and should not have been done as military and civilians are moving out. Who was at fault, and where lies the responsibility with. There are those who see the problem as a matter of logistics something here and now and those who explore the history of conflict and try to explain it. Either side however does not note perhaps the most significant issue; that the continuation of wars and the maintenance of conflict around the world is not a failure of politics, but an international crime that is largely neglected. For context, lets explore this conflict’s origin; 20 years ago one of the wealthiest countries on the planet declared war to one of the poorest; the military operations carried the code name “Enduring Freedom”! perhaps irony is lost on those in positions of power. The war was declared as part of a wider foreign policy by the wealthy country (and its allies) on what was called the “war on terror”. It ostensibly aimed to curtail, and eventually defeat, extremist groups around the world from using violence and oppressing people. Yes, that is right, they used war in order to stop others from using violence.

In criminology, when we talk about violence we have a number of different ways of exploring it; institutional vs interpersonal or from instrumental to reactive. In all situations we anticipate that violence facilitates more violence, and in that way, those experiencing it become trapped in a loop, that when repeated becomes an inescapable reality. War is the king of violence. It uses both proactive and emotional responses that keep combatants locked in a continuous struggle until one of them surrenders. The victory attached to war and the incumbent heroism that it breeds make the violence more destructive. After all through a millennia of warfare humans have perfected the art of war. Who would have thought that Sun Tzu’s principles on using chariots and secret agents would be replaced with stealth bombers and satellites? Clearly war has evolved but not its destructive nature. The aftermath of a war carries numerous challenges. The most significant is the recognition that in all disputes violence has the last word. As we have seen from endless conflicts around the world the transition from war to peace is not as simple as the signing of a treaty. People take longer to adjust, and they carry the effects of war with them even in peace time.

In a war the causes and the motives of a war are different and anyone who studied history at school can attest to these differences. It is a useful tool in the study of war because it breaks down what has been claimed, what was expected, and what was the real reason people engaged in bloody conflict. The violence of war is different kind of violence one that takes individual disputes out and turns people into tribes. When a country prepares for war the patriotic rhetoric is promoted, the army becomes heroic and their engagement with the war an act of duty. This will keep the soldiers engaged and willing to use their weapons even on people that they do not know or have any personal disputes with. Among wealthy countries that can declare wars thousands of miles away this patriotic fervour becomes even more significant because you have to justify to your troops why they have to go so far away to fight. In the service of the war effort, language becomes an accomplice. For example they refrain from using words like murder (which is the unlawful killing of a person) to casualties; instead of talking about people it is replaced with combatants and non-combatants, excessive violence (or even torture) is renamed as an escalation of the situation. Maybe the worst of all is the way the aftermath of the war is reflected. In the US after the war in Vietnam there was a general opposition to war. Even some of the media claimed “never again” but 10 year after its end Hollywood was making movies glorifying the war and retelling a different rendition of events.

Of course the obvious criminological question to be asked is “why is war still permitted to happen”? The end of the second world war saw the formation of the United Nations and principles on Human Rights that should block any attempt for individual countries to go to war. This however has not happened. There are several reasons for that; the industry of war. Almost all developed countries in the world have a military industry that produces weapons. As an industry it is one of the highest grossing; Selling and buying arms is definitely big business. The UK for example spends more for its defence than it spends for the environment or for education. War is binary there is a victor and the defeated. If a politician banks their political fortunes on being victorious, engaging with wars will ensure their name to be carved in statues around cities and towns. During the war people do not question the social issues; during the first world war for example the suffragettes movement went on a pause and even (partly) threw itself behind the war effort.

What about the people who fight or live under war? There lies the biggest crime of all. The victimisation of thousands or even millions of people. The civilian population becomes accustomed to one of the most extreme forms of violence. I remember my grandmother’s tales from the Nazi occupation; seeing dead people floating in the nearby river on her way to collect coal in the morning. The absorption of this kind of violence can increase people’s tolerance for other forms of violence. In fact, in some parts of the world where young people were born and raised in war find it difficult to accept any peaceful resolution. Simply put they have not got the skills for peace. For societies inflicted with war, violence becomes currency and an instrument ready to be used. Seeing drawings of refugee children about their home, family and travel, it is very clear the imprint war leaves behind. A torched house in a child’s painting is what is etched in their mind, a trauma that will be with them for ever. Unfortunately no child’s painting will become a marble statue or receive the honours, the politicians and field marshals will. In 9/11 we witnessed people jumping from buildings because a place crashed into them; in the airport in Kabul we saw people falling from the planes because they were afraid to stay in the country. Seems this crime has come full circle.