Home » Colonialism

Category Archives: Colonialism

Crime I: Nature or Nurture?

This is a two-part blog on embracing some of the criminological theory origin stories in the Western hemisphere. Is crime the product of bad genes or bad society? Are we born or made criminal?

In this week we shall be exploring our understanding of biological theories originating back in the 19th century with the “born criminal”. The following week we will look at the role of the environment.

The born criminal.

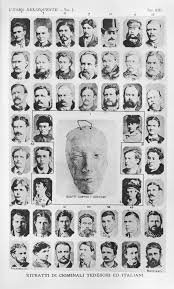

In 1871 Cesare Lombroso became the director at the Pesaro Mental Health Hospital (asylum) that housed the clinically insane. In that environment he examined the anatomical anomalies of residents in laboratory conditions. The era of the scientific exploration of deviance had begun. These meticulous explorations of bodily features and skulls formed the basis for his later thesis on The Born Criminal. The basis of his criminal population were residents of the asylum. His control group (i.e. those deemed non-criminal) were soldiers. Later, these were combined with the population of inmate prison population Lombroso and his associates visited. As he assumed an academic role in one of the finest Italian universities the world read his seminal publication of L’uomo delinquente {The Born Criminal] .Which in 1876 became one of the publications that influence the work of its contemporaries. In later years studied in exactly the same way. criminality in women using sex workers and prisoners as his research population cumulating into the 1893 publication of La Donna Delinquente: La prostituta e la donna normale [The Criminal Woman: The Prostitute and the Normal Woman.

His theoretical reach transcended borders and became widely read in the English-speaking world. This is an origin story according to numerous textbooks about the biological understanding of criminality. When embellished with some of the original quotes this becomes a theory of crime that explains different criminalities and makes the most significant leap that combines scientific rationale with crime. The methodology of anthropometry is a careful measuring of human features, prominently skulls! The main theoretical “innovation” was the recognition of a state of atavism; a regression onto a prior evolutionary stage for those engaged in crime.

A theory of crime on the born criminal seemed as a logical step at a time hailed as an era of discovery and exploration. A time that social and political movements in Europe asked profound questions about self and society. This narrative of course largely overlooks that whilst West European and US philosophers are posing these questions their elites and establishment are preoccupied with colonialism and dominance. In fact, it is the time European conflict around the world for dominance intensified. By the late 19th century, the European powers will try to manage their dominance in other continents by carving the world according to their own interests. The Berlin conference of 1884-85 is the culmination of such European competition and led to the split of Africa into zones of colonial influence.

In what way is The Born Criminal related with colonialism?

The theory of the “born criminal” breaks down humanity into two; the “normals” and the “atavists” which conveniently separates us from them. The criminal becomes the outcome of a lack of civilisation that can be seen in their physical features. There is history in separating people for the sake of exploitation, subjugation and even genocide. In this context of using civilisation (solely European) as the feature of separation is something previously seen in the colonisation of the Americas. When the European explorers landed in a new (for their map’s) continent the question of whom it belongs to was answered using religious decree. Several popes described the native population of these “discovered lands” as uncivilised and unworthy of human rights. It was the papal “Doctrine of Discovery” that denied the indigenous people rights to their land because uncivilised, faithless people (calling it terra nullus or empty land) do not count. Therefore, this separation for discrimination is not new, but Lombroso brought some scientific veneer to it.

It is important to remind all that “the born criminal” theory was widely discredited already in the early 20th century, when data analysis found no support for atavism and the biological features seemingly associated with criminality. Yet still this approach seems to capture even today some interest in the collective criminological imagination. Can you tell the prospective criminality reflected in someone’s gaze? It is a question that people still wonder, despite any lack of empirical or scientific data. The line of separating criminals from non-criminal provides an arbitrary differentiation that offers some clarity of how criminals should look, in a similar fashion to separating the “civilised” from the “savages”. In this overreaching correlation crime becomes the act of the uncivilised. It can also be flipped over and the uncivilised are the criminals contributing to the continuous fear of those who see the foreigner with suspicion.

A theory about the biological origins on crime that has offered us an explanation of the born criminal that has no scientific evidence but carries populist imagination because we take comfort in differentiating people. Next week we shall be exploring a theory that explores of the environmental factors of crime.

Cost of Living Crisis: Don’t worry it’s the Sovereign’s Birthday!*

On Saturday 31st May 2025, on Wellington Arch there was an increased presence of police. It was a sunny, albeit windy day in central London, and lots of people (tourists and locals) raised questions around why there appeared to be an increased police presence on this final Saturday of the May half term. At around 1pm approximately, what appeared to be hundreds of uniformed royal officers on horseback paraded through Wellington Arch into Hyde Park. They appeared to have come from Buckingham Palace. It was quite a sight to see! Every Sunday, there is a small parade, known as Changing of the Guard, but this was a substantially bigger ordeal. There is usually 2/3 police bikes that escorts the parade on the Sunday but not the numbers of Police (vans, bikes and officers) out on this sunny Saturday. It is over quickly, but the amount of people power, and I would imagine money, this has used seems quite ridiculous.

It turns out the large parade on May 31st was a ‘practice run’ for the Trooping of the Colour, which will occur on Saturday 15th June 2025. The Trooping of the Colour marks the ‘official’ birthday of the British Soverign and has done so for over 260years (Royal Household, 2025). It involves “Over 1400 parading soldiers, 200 horses and 400 musicians […] in a great display of military precision, horsemanship and fanfare to mark the Sovereign’s official birthday” (Royal Household, 2025). Having seen this every year, it is quite a spectacle and it does generate a buzz and increase in tourism to the area every year. I know the local small businesses in the surrounding areas are grateful for the increase in people, and it draws tourists in globally to view which generates money for the economy. But given the poverty levels visibly evident in London (not to mention those which are hidden), is this a suitable spend of money? Add on the more alarming issues with the monarchy and what it represents steeped in the clutches of empire and fostering hierarchies and inequalities, should this ‘celebration’ still be occurring? It’s the ‘Official’ Birthday of the Sovereign, but how many Birthdays does one need?

According to a Freedom of Information Request, the Ministry of Defence claimed in 2021, the Trooping of the Colour cost taxpayers around £60,000 (not the cost of the event, as there would have been other monies attached to funding this). Imagine what good this money could do: the people it could feed, the people it could provide shelter for, the medical treatment or research it could fund! Given this was 2021, I am going to hazard a guess that in 2025 this is going to cost significantly more. And for what? The Monarchy is the visual embodiment of empire, and according to the National Centre of Social Research, support for and interest in the Monarchy has been steadily declining for the past decade (NCSR, 2025). So even if people choose to ignore the horrific past of the British Sovereigns, it would appear that many are not interested in the Monarchy, regardless of its history (NCSR, 2025). I am aware the Royal family, and these ‘celebrations’, bring in income and generates global interest which translates to the argument that having a Monarchy is ‘economically viable’, but when you look at the disadvantage elsewhere, especially in London, its hard not to question clinging on to such traditions and the expense of meeting people’s basic needs. There is no critical consideration of what maintaining these traditions might suggest, or how they might impact those most effected by the British Empire and Colonialism. So why are these ‘celebrations’ persisting, and why are they having a practice run when steps away from them, in the underpass by Hyde Park Tube station there are people sleeping rough and begging for food? It feels as though there is a serious disconnect between what society needs (affordable homes, food, reasonable living wage, rehabilitation programmes, support and care) and what society will get (a glorified Birthday party for the ‘British Sovereign’).

*Note: the title of the blog should be read dripping in sarcasm.

References:

The National Centre for Social Research (2024) British Social Attitudes: Support for the Monarchy Falls [online]. Available at: https://natcen.ac.uk/news/british-social-attitudes-support-monarchy-falls-new-low [Accessed 4th June 2025].

The Royal Household (2025) What is Trooping the Colour? [Online]. Available at: https://www.royal.uk/what-is-trooping-the-colour#:~:text=The%20Trooping%20of%20the%20Colour,mark%20the%20Sovereign’s%20official%20birthday [Accessed 4th June 2025].

The colour of my skin

In recent weeks one politician, let’s call him “Doug” questioned the colour of another politician, let’s call her “Karen”. According to Doug, Karen decided to change the colour of her skin from brown to black. The way the colour change took place was presented as capricious and confusing. This little discussion took place in an event organised by the National Association of Black Journalists and it raised some very negative reactions namely on Doug’s audacity to interfere with the right of another person, in this case Karen, to self-identify and chose her own racial identity.

Perhaps these comments will be remembered or forgotten, but regardless they resonate with me because racial profiling and race identification is still a highly contested term in judicial processes namely law enforcement. It is even more controversial when considering the origins of these racial profiling and attribution. One word: colonialism! I appreciate that this is something that we converse about when we are talking about historical events, on empire expansion and exploitation, that led to genocide and slavery, but this is when I actually think that is partially the picture. Maybe because the roots on colonialism live with us and they still influence our social reality.

Colonialism turned skin colour into a commodity. It became part of the empire’s structure and all European and European influenced empires (i.e. USA or Australia) stand accused of their influence in criminalising skin and racial features. This influence is long lasting and its indelibly connected with the glorious past of all empires. Colourism and racial profiling were exploited to justify some of the most heinous crimes in human history.

To explain; colonialism sounds like an act that happened and eventually ended in time of British abolition of slavery and in US the Emancipation proclamation. After that, the world fought against it and all forms of it internationally entering article 4 of the UN convention. All is well! On the contrary! My point is that colonialism is far more insidious and deceitful. People presume that skin colour is a description of attributes and for millennia it was; the intensity of imperial exploitation of people used the colour of the skin as an obvious demarcation of racial separation. That allowed the imperial powers to keep different populations under control. Colour became the vehicle of oppression and subjugation. Empires thrived in dividing the population, utilising race and colour as a wedge that will make it difficult to understand their connected history of repression, making it difficult for people to rise against the tyranny of imperialism.

Consider the following. A fourth or fifth child of a Scottish labourer back in the early 19th century. Barely educated in reading and writing in a village in the highlands from a family that is hardly making ends meet. At age 17 he will join the British red coats or scarlet tunics, to be sent anywhere in the empire. This young man with hardly any life experience will be travelling across the world, using the privilege of his uniform to take, steal and do whatever he wants with impunity.[1] Years after he will return back to the village he came from with wealth and loot. His contemporaries will hail him as a success. In a garage sale today, a delightful old lady is holding a precious tea cup left by her beloved great-grandfather.

She holds it in her trembling hands as if the tea cup is talking to her, giving her meaning. Who can dare to tell this lovely old lady the history of this cup; the blood and pain that it contained long before it travelled across continents? This is why colonialism is so insidious because it’s subversive making people of the present and the future, custodians of that past, even unbeknown to them.

Of course, in the original instance between Doug and Karen, what is left out is the biggest and most challenging facet. That purity of race is a great read for those studying ethnology in the early 20th century, but we now know that people’s colours and races are a mixture of transgenerational journeys. People who identify as mixed race, a constituency of people, largely ignored by colonialism because it did not fit into their absurd sense of race classification, is rising.

Empire with its tales of heroism and greatness makes people yearn for a past that never existed, from a partial perspective that benefited the oppressors, minimising the impact it had on those who they oppressed. People, their cultures and most importantly their physiology become the casualties of said greatness. Years and years ago, in conversation with a dear Persian friend I realised that Alexander was Great for me but for Darius, my friend, he was Alexander the Accursed. If we can see beyond the “greatness” of our own past, perhaps we can read human history more accurately, where human attributes are just that and the colour of the skin should bear no consequences on people’s life or death.

[1] Similarly to the actions of a Scottish nobleman who stripped off the sculptures of a national monument; something akin to a sport of plunder among the European empires.

By whose standards?

This blog post takes inspiration from the recent work of Jason Warr, titled ‘Whitening Black Men: Narrative Labour and the Scriptural Economics of Risk and Rehabilitation,’ published in September 2023. In this article, Warr sheds light on the experiences of young Black men incarcerated in prisons and their navigation through the criminal justice system’s agencies. He makes a compelling argument that the evaluation and judgment of these young Black individuals are filtered through a lens of “Whiteness,” and an unfair system that perceives Black ideations as somewhat negative.

In his careful analysis, Warr contends that Black men in prisons are expected to conform to rules and norms that he characterises as representing a ‘White space.’ This expectation of adherence to predominantly White cultural standards not only impacts the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes but also fails to consider the distinct cultural nuances of Blackness. With eloquence, Warr (2023, p. 1094) reminds us that ‘there is an inherent ‘whiteness’ in behavioural expectations interwoven with conceptions of rehabilitation built into ‘treatment programmes’ delivered in prisons in the West’.

Of course, the expectation of adhering to predominantly White cultural norms transcends the prison system and permeates numerous other societal institutions. I recall a former colleague who conducted doctoral research in social care, asserting that Black parents are often expected to raise and discipline their children through a ‘White’ lens that fails to resonate with their lived experiences. Similarly, in the realm of music, prior to the mainstream acceptance of hip-hop, Black rappers frequently voiced their struggles for recognition and validation within the industry due similar reasons. This phenomenon extends to award ceremonies for Black actors and entertainers as well. In fact, the enduring attainment gap among Black students is a manifestation of this issue, where some students find themselves unfairly judged for not innately meeting standards set by a select few individuals. Consequently, the significant contributions of Black communities across various domains – including fashion, science and technology, workplaces, education, arts, etc – are sometimes dismissed as substandard or lacking in quality.

The standards I’m questioning in this blog are not solely those shaped by a ‘White’ cultural lens but also those determined by small groups within society. Across various spheres of life, whether in broader society or professional settings, we frequently encounter phrases like “industry best practices,” “societal norms,” or “professional standards” used to dictate how things should be done.

However, it’s crucial to pause and ask:

By whose standards are these determined?

And are they truly representative of the most inclusive and equitable practices?

This is not to say we should discard all concepts of cultural traditions or ‘best practices’. But we need to critically examine the forces that establish standards that we are sometimes forced to follow. Not only do we need to examine them, we must also be willing to evolve them when necessary to be more equitable and inclusive of our full societal diversity.

Minority groups (by minority groups here, I include minorities in race, class, and gender) face unreasonably high barriers to success and recognition – where standards are determined only by a small group – inevitably representing their own identity, beliefs and values.

So in my opinion, rather than defaulting to de facto norms and standards set by a privileged few, we should proactively construct standards that blend the best wisdom from all groups and uplift underrepresented voices – and I mean standards that truly work for everyone.

References

Warr, J. (2023). Whitening Black Men: Narrative Labour and the Scriptural Economics of Risk and Rehabilitation, The British Journal of Criminology, Volume 63, Issue 5, Pages 1091–1107, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azac066

Christmas Toys

In CRI3002 we reflected on the toxic masculine practices which are enacted in everyday life. Hegemonic masculinity promotes the ideology that the most respectable way of being ‘a man’ is to engage in masculine practices that maintain the White elite’s domination of marginalised people and nations. What is interesting is that in a world that continues to be incredibly violent, the toxicity of state-inflicted hegemonic masculinity is rarely mentioned.

The militaristic use of State violence in the form of the brutal destruction of people in the name of apparent ‘just’ conflicts is incredibly masculine. To illustrate, when it is perceived and constructed that a privileged position and nation is under threat, hegemonic masculinity would ensure that violent measures are used to combat this threat.

For some, life is so precious yet for others, life is so easily taken away. Whilst some have engaged in Christmas traditions of spending time with the family, opening presents and eating luxurious foods, some are experiencing horrors that should only ever be read in a dystopian novel.

Through privileged Christmas play-time with new toys like soldiers and weapons, masculine violence continues to be normalised. Whilst for some children, soldiers and weapons have caused them to be victims of wars with the most catastrophic consequences.

Even through children’s play-time the privileged have managed to promote everyday militarism for their own interests of power, money and domination. Those in the Global North are lead to believe that we should be proud of the army and how it protects ‘us’ by dominating ‘them’ (i.e., ‘others/lesser humans and nations’).

Still in 2023 children play with symbolically violent toys whilst not being socialised to question this. The militaristic toys are marketed to be fun and exciting – perhaps promoting apathy rather than empathy. If promoting apathy, how will the world ever change? Surely the privileged should be raising their children to be ashamed of the use of violence rather than be proud of it?

Saluting Our Sisters: A Reflection on the Living Ghost of the Past

Sarah Baartman. Image source: https://shorturl.at/avLO4

In the 20th century, many groups of people who had been overpowered, subdued, and suppressed by imperialist expansionist movements under arbitrary boundaries began challenging their subjugation. These emancipation struggles resulted in the emergence of quasi-independent, self-governed African nation-states. However, avaricious socio-economic opportunists were aided into political leadership and have continued to perpetuate imperial interests while crippling their own emerging nations. Decades later, it has become clear that these ‘new states’ have become shackled under the grips of strong and powerful men who lead a backward and dysfunctional system with the majority of people impoverished while they enervate justice and political institutions.

Prior to this, the numerous nation states now recognised as African states had developed their distinct social, political, and economic systems which emerged from and reflected their distinctive norms and cultural values. Barring communal disputes and conflicts, robust inter-communal associations, interaction, and commerce subsisted amongst the nations, and paced socio-economic developments were occurring until external incursions under different guises began. Notably, the tripartite monsters of transatlantic slave trade, pillage of natural resources, and colonisation which not only lasted for centuries, disrupted the steady pace and development of these nations. It destroyed all existing social fabric and capital of the people, and forcefully installed a religious, socio-political, and economic systems that are alien to the people.

Ironically, while the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism were perpetuated under the guise of a “civilizing mission,” it took over three centuries for the “civilised” to realise that these abhorrent incursions were far from being civilising, and that they themselves required the civilisation they purported to be administering. However, while one might imagine that this awareness would lead to remorse and guilt-tripped sincere repentance for the pillage, pain, and atrocities, the abolition and relinquishing of political power to natives, the following events symbolized the contrary. Neo-colonialism was born, and international systems and conglomerates have continued the pillage on different fronts as aided by the greedy political class. Thus, it is unsurprising that yet again, strong, and powerful men are revolting against and deposing the self-perpetuating, avaricious socio-economic opportunists who wield political power against the interests of their nations in series of military coup d’état.

It is clear that the legacy of exploitation and subjugation has brought about a new set of challenges. Leaders entrusted with the responsibility of fostering prosperity in their nations often succumbed to personal gain, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation reminiscent of the imperialist era. This grim reality creates a stark contrast: while the majority of citizens are trapped in poverty, a powerful minority wields disproportionate influence, eroding the foundations of justice, economic prosperity, and political stability. As a result, for the vulnerable, seeking safety, economic freedom, and escaping from dysfunctional systems through deadly and illegal migration to other parts of the world becomes the only viable option. However, unbeknownst to many, the lands they risk everything to reach are grappling with their own challenges, including issues of acceptance and association with once labelled ‘uncivilized’ peoples.

Black History Month sheds light on these challenges faced by the black community and other marginalized ethnic groups globally. This year, the theme ‘Saluting our Sisters’ invites us to reflect on the contributions of Black women to society and the challenges they continue to face. It is also important to reflect deeply on how we consciously or unconsciously perpetuate rather than disprove, discourage, and distance ourselves from sustaining and growing the living ghost of the past. As Chimamanda urges, perhaps considering a feminist perspective in our actions, practices, and behaviour can be a powerful step toward recognizing and acknowledging how we perpetuate these problems. Dear Sister, I admire and salute you for your resilience and tenacity in making the world a better place.

Unravelling the Niger Coup: Shifting Dynamics, Colonial Legacies, and Geopolitical Implications

On July 26, the National Council for Safeguarding the Homeland (CNSP) staged a bloodless coup d’état in Niger, ousting the civilian elected government. This is the sixth successful military intervention in Africa since August 2020, and the fifth in the Sahel region. Of the six core Sahelian countries, only Mauritania has a civilian government. In 2019, it marked its first successful civilian transition of power since the 2008 military intervention, which saw the junta transitioning to power in 2009 as the civilian president.

Military intervention in politics is not a new phenomenon in Africa. Over 90% of African countries have experienced military interventions in politics with over 200 successful and failed coups since 1960 – 1, (the year of independence). To date, the motivation of these interventions revolves around insecurity, wasteful and poor management of state resources, corruption, and poor and weak social governance. Sadly, the current situation in many African countries shows these indicators are in no short supply, hence the adoption of coup proofing measures to overcome supposed coup traps.

The literature evidences adopting ethnic coup proofing dynamics and colonial military practices and decolonisation as possible coup-proofing measures. However, the recent waves of coups in the Sahel defer this logic, and are tilting towards severing ties with the living-past neocolonial presence and domination. The Nigerien coup orchestrated by the CNSP has sent shockwaves throughout the region and internationally over this reason. Before the coup, Mali and France had a diplomatic row. The Malian junta demanded that France and its Western allies withdraw their troops from Mali immediately. These troops were part of Operation Barkhane and Taskforce Takuba. A wave of anti-French sentiments and protests resulted over the eroding credibility of France and accusation of been an occupying force. Mohamed Bazoum, the deposed Nigerien president, accepted the withdrawn French troops and its Western allies in Niger. This was frowned at by the Nigerien military, and as evidenced by the bloodless coup, similar anti-French sentiments resulted in Bazoum’s deposition.

The ousting of President Bazoum resulted in numerous reactions, including a decision by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), of which Niger is a member and is currently chaired by Nigerian President Bola Ahmed Tinubu. ECOWAS demanded the release and reinstatement of President Bazoum, imposed economic sanctions, and threatened military intervention with a one-week ultimatum. Some argued that the military intervention is unlikely, and some member states pledged support to the junta. At the end of the ultimatum, ECOWAS activated the deployment of its regional standby force but it remains unclear when it will intervene and what the rules of engagement will be. Nonetheless, the junta considers any such act as an aggression, and in addition to closing its airspace, it is understood to have sought support from Wagner, the Russian mercenary.

Amongst the citizenry, while some oppose the military intervention, there is popular support for both the intervention and the military with thousands rallying support for the junta. On 6 August, about 30,000 supporters filled the Niamey stadium chanting and applauding the military junta as they parade the crowd-filled stadium. Anti-French sentiments including a protest that led to an attack on the French embassy in Niger followed the declaration of the coup action. In the civil-military relations literature, when a military assumes high political roles yet has high support from society over such actions, it is considered as a popular praetorian military (Sarigil, 2011, p.268). While this is not a professional military attribute (Musa and Heinecken, 2022), it is nonetheless supported by the citizenry.

In my doctoral thesis, I argued that in situations where the population is discontent and dissatisfied with the policies of the political leadership, a civil-military relations crisis could result. I argued that “as citizens are aware that the military is neither predatory nor self-serving, they are happy trusting and supporting the military to restore political stability in the state. It is possible that in situations where political instability becomes intense, large sections of the citizenry could encourage the military to intervene in politics” (Musa, 2018, p.71). The recent waves of military intervention in Africa, together with anti-colonial sentiments evidences this, and further supports my argument on the role of the citizenry in civil-military relations. For many Nigeriens including Maïkol Zodi who leads an anti-foreign troops movement in Niger, the coup symbolises the political independence and stability that Francophone Africa has long desired.

Thus, as the events continue to unfold, I would like to end this blog with some questions that I have been thinking about as I try to make sense of this rather complex military intervention. The intervention is affecting international relations and has the potential to destabilise the current power balance between the major powers. It could also lead to a military conflict in Africa, which would be a disaster for the continent.

- How have recent coups in the Sahel region signalled a shift away from colonial legacies, and how are these sentiments reshaping political dynamics?

- What is the significance of the diplomatic tensions between Mali and France, and how might they have influenced the ousting of President Bazoum and the reactions to it?

- Given the surge in military interventions in politics across the Sahel region, how does this trend reflect evolving dynamics within the affected countries, and does this has the potential to spur similar interventions in other African States?

- What lessons can be drawn from Mauritania’s successful transition from military to civilian rule in 2019, and how might these insights contribute to diplomatic discussions around possible transition to civilian rule in Niger?

- Are the decisions of ECOWAS influenced by external pressures, how effective is ECOWAS’s approach to addressing coups within member states, and how does the Niger coup test the regional organization’s capacity for conflict resolution?

- To what extent do insecurity, mismanagement of resources, corruption, and poor governance collectively contribute to the susceptibility of African nations to military interventions?

- How can African governments strike a balance between improving the quality of life and coup-proofing measures, and which is most effective for preventing or mitigating the risk of military interventions?

- What are the potential ramifications of the coup on the geopolitical landscape, especially in terms of altering power dynamics among major players?

- What are the implications of the coup for regional stability, and how might it contribute to the potential outbreak of conflict and could it destabilize ongoing counterterrorism efforts and impact cooperation among countries in addressing common security threats?

- Why do widespread demonstrations of support for the junta underscore the sentiments of political independence and stability that resonate across Francophone Africa?

- Given the complexities of the situation, what measures can be taken to ensure long-term stability, governance improvement, and democratic progress in Niger?

- Ultimately, is the western midwifed democracy in Africa serving its purpose, and given the poor living conditions of the vast populace in African countries as measured against all indices, can these democracies serve Africans?

Navigating these questions is essential for comprehending the implications of the coup and the potential outcomes for Niger and its neighbours. In an era where regional stability and international relations are at stake, a nuanced understanding of these multifaceted issues is imperative for shaping informed responses and sustainable solutions.

References

Musa, S.Y. (2018) Military Internal Security Operations in Plateau State, North Central Nigeria: Ameliorating or Exacerbating Insecurity? PhD, Stellenbosch University. Available from: https://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/104931. [Accessed 7 March 2019].

Musa, S.Y., Heinecken, L. (2022) The Effect of Military (Un)Professionalism on Civil-Military Relations and Security in Nigeria. African Security Review. 31(2), 157–173.

Sarigil, Z. (2011) Civil-Military Relations Beyond Dichotomy: With Special Reference to Turkey. Turkish Studies. 12(2), 265–278.

An alternative Christmas message

Sometime in October stores start putting out Christmas decorations, in November they slowly begin to play festive music and by December people organise office parties and exchange festive cards. For the best part of the last few decades these festive conventions seem to play a pivotal role in the lead up to Christmas. There are jumpers with messages, boxes of chocolates and sweets all designed to spread some festivity around. For those working, studying, or both, their December calendar is also a reminder of the first real break for some since summer.

The lead up to Christmas with the music, stories and wishes continues all the way to the New Year when people seem to share their goodwill around. Families have all sorts of traditions, putting up the Xmas tree on this day, ordering food from the grocers on that day, sending cards to friends and family by that day. An arrangement of dates and activities. On average every person starts in early December recounting their festive schedule. Lunch at mum’s, dinner at my brother’s, nan on Boxing Day with the doilies on the plates, New Years Eve at the Smiths where Mr Smith gets hilariously drunk and starts telling inappropriate jokes and New Year’s at the in-laws with their sour-faced neighbour.

People arrange festivities to please people around them; families reunite, friends are invited, meaningful gifts are bought for significant others and of course buy we gifts for children. Oh, the children love Christmas! The lights, the festive arrangements, the delightful activities, and the gifts! The newest trends, the must have toys, all shiny and new, wrapped up in beautiful papers with ribbons and bows. In the festive season, we must not forget the kind words we exchange, the messages send by local communities, politicians and even royalty. Words full of warmth, well-meaning, perspective and reflection. Almost magical the sights and sounds wrapped around us for over a month to make us feel festive.

It is all too beautiful, so you can be forgiven to hardly notice the lumbering shadow, at the door of an abandoned shop. Homelessness is not a lifestyle as despicably declared by a Conservative councillor/newspapers decades ago. It is the human casualty of those who have been priced out in the war of life. Even since the world went into a deep freeze due to the recession over a decade ago and the world is still in the clutches of that freeze. More people read about Christmas stories in books and in movies, because an even increasing number of people do not share the experience. Homelessness is the result of years of criminal indifference and social neglect that leads more people to live and experience poverty. A spectre is haunting Europe, the spectre of homelessness. There is no goodwill at the inn whilst the sins of the “father” are now returning in the continent! Centuries of colonial oppression across the world lead to a wave of refugees fleeing exploitation, persecution, and crippling poverty. Unlike the inn-keeper and his daughter, the roads are closed, and the passages are blocked. Clearly, they don’t fit with the atmosphere… nor do the homeless. Come to think of it, neither do the old people who live alone in their cold homes. None of these fit with the festive narrative.

As I walked down a street I passed a homeless guy is curled up in a shop door. A combination of cardboard, sleeping bag and newspapers all jumbled together. Next to him a dog on the cardboard and around them fairy lights. This man I do not know, his face I have not seen, his identity I ignore; but I imagine that when he was born, there was someone who congratulated his mother for having a healthy boy. Now he is alone, fortunate to have a canine companion, as so many do not have anyone. What stands out is that this person, who our festive plans had excluded, is there with his fairy lights, maybe the most festive of all people, without a burgundy coat, I hear some people like these days.

It is so difficult to say Merry Christmas this year. In a previous entry the world cup and its aftermath left a bitter taste in those who believe in making a better world. The economic gap between whose who have and those who do not, increases; the social inequalities deepen but I feel that we can be like that man with the fairy lights, fight back, rise up and end the party for those who like to wear burgundy, or those who like to speak for world events, at a price.

Merry Christmas, my dear criminologists, the world can change, when we become the agents of change.

The Origins of Criminology

The knife was raised for the first time, and it went down plunging into naked flesh; a spring of blood flowed cascading and covering all in red. The motion was repeated several times. Abel fell to his death and according to scriptures this was the first crime. Cain who wielded the knife roamed the earth until his demise. The fratricide that was committed was the first recorded murder and the very first crime. A colleague tried to be smart and pointed that the first crime is Eve’s violation in the garden with the apple, but I did point out that according to Helena Kennedy QC, she was framed! In the least Eve’s was a case of entrapment which is criminological but leaves the first crime vacant. So, murder it is! A crime of violence that separates aggressor and victim.

The response to this crime is retribution. In the scriptures a condemnation to insanity. In later years this crime formed the basis of the Mosaic Law inclusive of the 10 commandments and death as the indicative punishment. In the Ancien Régime the punishment became a spectacle on deterrence whilst the crowds denounced the evildoer as they were wheeled into the square! In modern times this criminality incorporated rehabilitation to offer the opportunity for the criminal to repent and make amends.

‘The first man who having enclosed a piece of ground bethought himself of saying “This is mine”’! This is an alternative interpretation of the first crime, according to Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762/1993: 192). In The Social Contract he identifies the first crime very differently from the scriptures. In this case the crime is not directed at a person but the wider community. The usurping of land or good in any manner that violates the rights of others is crime because it places individualism ahead of the common good. As in this crime there is no violence against the person, the way in which we respond to it is different. Imperialism as a historical mechanism accepts the infringement of property, rights, and human rights as a necessity in human interactions. The law here is primarily protected for the one who claims the land rather than those who have been left homeless. In this case, crime is associated with all those mechanisms that protect privilege and property. Soon after titles of land emerged and thereafter titles of people owning other people follow. The land becomes an empire, and the empire allows a man and his regime to set the laws to protect him and his interests. Traditionally empires change from territories of land to centres of government and control of people. The land of the English, the land of the Finnish, the land of the Zulu. In this instance the King become a figure and custom law subverts natural law to accommodate authority and power.

These two “original” crimes represent the diversity in which criminology can be seen; one end is the interpersonal psychological rendition of criminality based on the brutality of violence whilst on the other end is an exploration of wider structural issues and the institutional violence they incorporate. The spectrum of variety criminology offers is a curse and a blessing in one. From one end, it makes the discipline difficult to specify, but it also allows colleagues to explore so many different issues. Regardless of the type of crime category for any person attracted to the discipline there is a criminology for all.

Between these two polar apart approaches, it is interesting to note their interaction. In that it can be seen the interaction of the social and historical priorities of crime given at any given time. This historical positivism of identifying milestones of progression is an important source of understanding the evolution of social progression and movements. Let’s face it, crime is a social construct and as such regardless of the perspective is indicative of the way society prioritises perceptions of deviance.

Arguably the crimes described previously denote different schools of thought and of course the many different perspectives of criminology. A perfectly contorted discipline that not only adapts following the evolution of crime but also theorises criminality in our society. When you are asked to describe criminology, numerous associations come to mind, “the study of crime and criminality” the “discipline of criminal behaviours” “the social construction of crime” “the historical and philosophical understanding of crime in society across time” “the representation of criminals, victims, and agents in society”. These are just a few ways to explain criminology. In this entry we explore the origins of two perspectives; theology and sociology; image that the discipline is influenced by many other perspectives; so consider their “origin” story. How different the first crime can be from say a psychological or a biological perspective. The origins of criminology is an ongoing tale of fascinating specialisms.

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques, (1762/1993), The Social Contract and Discourses, tr. from the French by G.D.H. Cole, (London: Everyman’s Library)

Capitalism and tourism: an ethical conundrum

After a two-year delay in our holiday booking due to the Covid pandemic, my wife and I were fortunate enough to spend a two-week holiday in Cape Verde (Cabo Verde) on the island of Sal. We’ve been lucky enough to visit the islands several times over the last ten years. Our first visit was to Boa Vista but since the hotel that we liked no longer seemed to be available through our tour operators, we ended up going to Sal. When we first visited Boa Vista, there was little to be found outside of the hotel other than deserted beaches and the crashing of the Atlantic waves on the seashore. There was a very large hotel on the other side of the island and a smattering of smaller hotels dotted around, but that was it. After several visits we began to notice that other hotels were popping up along the seashore and there was a definite sense of development to cater for the holiday trade. The same can be said of Sal. The first hotel we visited had only just been built and there were the foundations of other buildings creeping up alongside but in the main, it seemed pretty deserted. Now though there are hotels everywhere and a fairly new very large one not that far away from where we stayed.

The first thing you notice as a visitor to the islands is that this is not an affluent country, far from it. Take a short trip into the town centre and you very rapidly see and sense the pervading poverty. This is a former Portuguese colony, and it comes as no surprise that it played a strategic role in the slave trade until the late nineteenth century whereupon it saw a rapid economic decline. Tourism has boosted the economy and plays a significant role in the country’s population, and this became even more evident during our latest visit. The country is only just recovering from the pandemic and several of the hotels were still mothballed as were the various businesses along the sea front. I’m not sure what the situation was or is in the country with regards to welfare, but I wouldn’t mind betting that they’d never heard of the word furlough, let alone implemented any such scheme. Quite simply no tourism means no work and no work means no wages, such as they are. In conversation with a number of the staff at the hotel, it became obvious that they were not only pleased we were there, but that they wanted us to return again. We were often asked if we would come back and one person, I spoke to pleadingly asked us to return as ‘we need the job’. Of course, it’s not just us that need to return, it’s all the tourists. Tourism supports so many aspects of the economy, not just jobs in hotels but local businesses as well. I think the fact that we keep going back there says something about the lovely people that we’ve been privileged to meet.

But then as I sat one night contently sipping a gin and tonic, debating whether I should have another before dinner, I began to think about whether all of this was ethical. The hotel we stayed in was part of a large international chain. Nearly all the hotels are part of large multinational corporations servicing their shareholders. Whilst my relaxation and enjoyment is great for me, it is on the back of the exploitative nature of the service industry. A business that probably doesn’t pay high wages, those working in the service industry in this country can probably attest to that, so goodness knows what it’s like in an impoverished place such as Cape Verde. My enjoyment therefore promotes exploitation and yet vis-a- vie enables people to have much needed work and pay. Of course, I may have this all wrong and the companies are pouring millions into the country to improve living standards for the inhabitants, and they may pay wages that are very reasonable. But somehow, because of the nature of business, and the eye on profit margins, I very much doubt it. When businesses consider business ethics, I wonder how far they cast the ethical net? As for me, it’s a bit of Catch 22, damned if you do and damned if you don’t. But then so much of life seems to be like that.