Home » Northampton

Category Archives: Northampton

The power of collaboration in Higher Education

In today’s rapidly evolving landscape of higher education, interdepartmental collaboration and knowledge sharing are becoming increasingly vital. By rapid evolution, I mean the pressing challenges we face, including rising costs and finances, issues in student engagement and attendance, digital transformation and rise of new technologies, growing concerns about student wellbeing, and most importantly, the critical need to ensure a strong, positive student experience in the face of these challenges. While the idea of interdepartmental collaboration and knowledge sharing isn’t entirely new, its importance in addressing these complex issues cannot be overemphasised.

At my university, our faculty, the Faculty of Business and Law recently celebrated its ‘Faculty Best Practice Day’ on Wednesday, September 4th. This event, led by our deanery, was an opportunity for departments within the faculty to showcase their hard work, innovations, and fresh ideas across various areas – from teaching and research to employability and beyond. Personally, I view this day as an opportunity to connect with colleagues from different departments – not just ‘catch-up’ but to gain insight into their current activities, exchange updates and share ideas on developments within our sector and disciplines.

This event is particularly intriguing to me for three distinct reasons. Firstly, the ability for department representatives to present their activities to faculty members is invaluable. Departmental reps showcase their growth strategies, techniques for strengthening student engagement, and the support they provide for students after graduating. Some present their research and future directions for the faculty. Others present their external partnership growth, evidence-based teaching pedagogy, and other innovative approaches for enhancing student experiences. Also, these presentations often highlight advancements in technology integration and initiatives aimed at encouraging diversity and inclusion within the HE. All these presentations are not just impressive – they’re incredibly informative and inspiring. Secondly, the event regularly reinforces the need for collaboration between departments – a cornerstone of academia. After all, no single person or department is an island of knowledge. So the ability to collaborate with other faculty members is crucial as it provides opportunities for synergy and innovation, showcases our strengths. Thirdly, and on a personal level, the event fosters the need to learn best practices from others, and this is an aspect that has been tremendously helpful for my career. Such interactions provide opportunity for stronger collegiality, including insights into different approaches and methods that I can adapt and apply in my own work in ways that I can contribute to my professional growth and effectiveness.

In the most recent event, I attended a session on cultural literacy and awareness. Despite my years in higher education, I was particularly surprised to learn new things about cultural awareness that pertain not only to international students but to home students as well. This was an excellent session that also offered the opportunity to connect with colleagues from other departments whom you only know through email exchanges, but rarely see in person.

In sum, I strongly encourage everyone in academia to attend such events or create one if you can. Contribute to and engage with these events – for they equip us to break down traditional barriers between disciplines and provides us with an opportunity to learn from each other with an open mind. This is something I will continue to advocate for because fostering interdepartmental collaboration isn’t just beneficial – it’s essential. It is through these collaborative efforts that we can truly innovate, improve, and excel in our mission to educate and inspire the next generation.

Everyone loves a man in uniform: The Rise and Fall of Nick Adderley

Some of our local readers will be familiar with the case of former Chief Constable Nick Adderley who was recently dismissed from Northamptonshire Police. The full Regulation 43 report can be found here and it provides an interesting, and at times, comical, narrative of the life and times of the now disgraced police officer.

The Regulation 43 report describes Adderley’s creation of a “false legend” of military service, whereby this supposed naval man fought bravely to protect the Falkland Islands (despite only being 15 when the conflict ended), rescued helicopters and ships in the height of battle, commanded men, was a military negotiator during the Anti-Duvalier protest movement in Haiti. In short, an all round real-life Naval action man! It’s pity for Adderley, that the Regulation 43 panel found none of this was true, instead a ‘Walter Mitty‘ like trail of lies were revealed throughout the investigation.

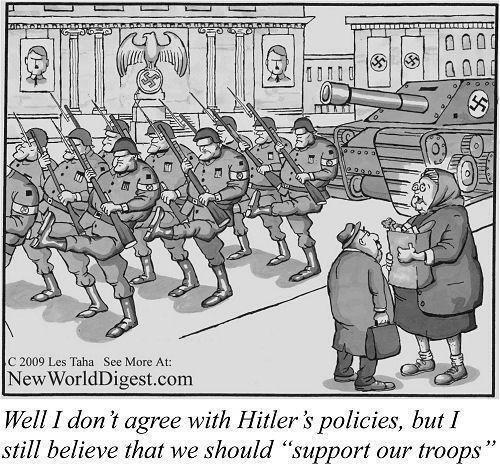

Nevertheless, not content with his brave military career, our intrepid hero decided he would take his considerable (in his estimation at least) skills into policing. First applying to Greater Manchester Police [GMP] (who turned him down on the grounds that there were ‘better candidates’) and then Cheshire Police. From Cheshire Police, he went to GMP and then to Staffordshire Police, finally arriving in Northamptonshire in the summer of 2018. Despite all of these different forces, all of the different application and promotion forms that our brave hero completed, not one person bothered to check that he was telling the truth. To check that this man, responsible for upholding law and order, was a fit candidate for the role. instead, I suspect, like so many it seems, we are so in love with our military and all its trappings, that we lose any sense of criticality when it comes to uniforms. After all who would dare to question a Chief Constable, whether a police officer, civilian worker or member of the public? Easier to keep parroting the mantra of “our brave boys”, than to think critically about institutions and their members, as the cartoon below demonstrates all too well.

At this point Adderley has been dismissed from Northamptonshire Police and banned from policing. In 2024 the Angiolini Inquiry published its report, which in part focused on police vetting and there is no doubt, post-Adderley the police as an institution, will undertake more soul searching. Additionally, some commentators have begun a campaign to have Adderley’s police pension reduced/removed. These matters will continue to rumble along for some time. But, in short, Adderley has been punished and publicly outed as a liar, but that does not begin to undo the immense harm his behaviour has inflicted on the community.

During his time at Chief Constable of Northamptonshire, Adderley called upon his supposed military history and experience to support his arguments and the decisions he made. For instance, the 2019 arming of Northamptonshire’s police with tasers or the 2020 launch of eight interceptors, described by Adderley as “a new fleet of crime-busting cars” or the 2021 purchase of “eight Yamaha WR450F enduro bikes“. To me, all of these developments scream the militarisation of policing. Since the very foundation of the Metropolitan Police in 1829, serving officers and the public have continually been opposed to arming the police, yet Adderley, with his military service, seemingly knew best. But what use is a taser, fast car or motorbike in everyday community policing, how do they help when responding to domestic abuse, sexual violence, or the very many mental health crises to which officers are regularly called? How do these expensive military “toys” ensure that all members of society feel protected and not just some communities? How can we ensure that tasers don’t do lasting harm to those subjected to their violence? Instead all of these developments scream a fantasy of both military and policing, one in which the hero is always on the side of the righteous, devoting his life to taking down the “baddies” by whatever means necessary.

Ultimately for the people of Northamptonshire we have to decide, can we view Adderley’s police leadership as the best use of taxpayers’ money, a response to evidence based policing or just a military fantasy of the man who lied? More importantly, the county and its police force will struggle to untangle Adderley’s web of lies and the harm inflicted on the people of Northamptonshire, making it likely that this entirely unevidenced push to militarise the police will continue unchecked.

Zemiological Perspective: Educational Experiences of Black Students at the University of Northampton

As a young Black female who has faced many challenges within the education system, particularly related to behavioral issues, I noticed how the system can unintentionally harm black students. I observed that Black children’s experiences in the education system are not always viewed from a deviant perspective, because they are not inherently deviant. The institutional harm faced by Black students is not always a ‘crime’ nor is it illegal, yet it is profoundly damaging.

This realisation prompted me to adopt a zemiological perspective, drawing upon the work of Hillyard et al. (2004) to highlight the subtle yet impactful harms faced by Black students in the educational system. My primary objective was to uncover the challenges these students face, as outlined in my initial research question: ‘To what extent can the experiences of Black students in higher education be understood as a form of social harm?’ To achieve this, I analysed the educational experiences of Black students at the University of Northampton. This involved reviewing the university’s access and participation plans, which detail the performance, access, and progression of various demographics within the institution, with a particular focus on BAME students.

Critical race theory (CRT) was the guiding theoretical framework for this research study. CRT recognises the multifaceted nature of racism, encompassing both blatant acts of racial discrimination and subtler, systemic forms of oppression that negatively impact minority ethnic groups (Gillborn, 2006). This theoretical approach is directly correlated to my research and was strongly relevant. This allowed me to gain insight into the underlying reasons behind the disparities faced by Black students in higher education. As well as enabling me to unpack the complexities of racism and discrimination, providing a comprehensive understanding of how these issues manifest and persist within the educational landscape.

Through conducting content analysis on the UON Access and Participation Plan document and comparing it to sector averages in higher education, four major findings came to light:

Access and Recruitment: The University of Northampton has made impressive progress in improving access and recruitment for BAME students, fostering diversity and inclusivity in higher education, and surpassing sector standards. Yet, while advancements are apparent, there remains a need for more comprehensive approaches to tackle systemic barriers and facilitate academic success across the broader sector.

Non-Continuation: Alarmingly, non-continuation rates among BAME students at the University of Northampton have surpassed the sector average, indicating persistent systemic obstacles within the education system. High non-continuation rates perpetuate cycles of disadvantage and limit opportunities for personal and professional growth.

Attainment Gap: Disparities in academic attainment between White and BAME students have persisted and continue to persist, reflecting systemic inequalities and biases within the academic landscape. UON is significantly behind the sector average when it comes to attainment gaps between BAME students and their white counterparts. Addressing the attainment gap requires comprehensive approaches that tackle systemic difficulties and provide targeted support to BAME students.

Progression to Employment or Further Study: UON is also behind the sector average in BAME students progression in education or further study. BAME students face substantial disparities in progression to employment or further study, highlighting the need for collaborative efforts to promote diversity and inclusivity within industries and professions. Addressing entrenched biases in recruitment processes is essential to fostering equitable opportunities for BAME students.

Contributions to Research: This research deepens understanding of obstacles within the educational system, highlighting the effectiveness of a zemiological perspective in studying social inequalities in education. By applying Critical Race Theory, the study offers insights that can inform policies aimed at fostering equity and inclusion for Black students.

The findings hold practical implications for policy and practice, informing the development of interventions to address disparities and create a more supportive educational environment. This research significantly contributes to our understanding of the experiences of Black students in higher education and provides valuable guidance for future research and practice in the field.

Aside from other limitations in my dissertation, the main limitation was the frequent use of the term ‘BAME.’ This term is problematic as it fails to recognise the distinct experiences, challenges, and identities of individual ethnic communities, leading to generalisation and overlooking specific issues faced by Black students (Milner and Jumbe, 2020). While ‘BAME’ is used for its wide recognition in delineating systemic marginalisation (UUK 2016 cited in McDuff et al., 2018), it may conceal the unique challenges Black students face when grouped with other minority ethnic groups. The term was only used throughout this dissertation as the document being analysed also used the term ‘BAME’.

This dissertation was a very challenging but interesting experience for me, engaging with literature was honestly challenging but the content in said literature did keep me intrigued. Moving forward, i would love Black students experiences to continue to be brought to light and i would love necessary policies, institutional practises and research to allow change for these students. I do wish i was more critical of the education system as the harm does more so stem from institutional practices. I also wish i used necessary literature to highlight how covid-19 has impacted the experiences of black students, which was also feedback highlighted by my supervisor Dr Paula Bowles.

I am proud of myself and my work, and i do hope it can also be used to pave the way for action to be taken by universities and across the education system. Drawing upon the works of scholars like Coard, Gillborn, Arday and many others i am happy to have contributed to this field of research pertaining to black students experiences in academia. Collective efforts can pave the way for a more promising and fairer future for Black students in education.

References

Gillborn, D. (2006). Critical Race Theory and Education: Racism and anti-racism in educational theory and praxis. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 27 (1), 11–32. [Accessed 21 April 2024]

Hillyard, P., Pantazis, C., Tombs, S. and Gordon, D., (Eds), (2004). Beyond Criminology: Taking Harm Seriously, London: Pluto Press.

Milner, A. and Jumbe, S., (2020). Using the right words to address racial disparities in COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health, 5(8), pp. e419-e420

Mcduff, N., Tatam, J., Beacock, O. and Ross, F., (2018). Closing the attainment gap for students from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds through institutional change. Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 20(1), pp.79-101.

Things I Miss, or Introverts vs Coronavirus

The thing I hate most about self-isolation is how quickly I eased into this new pace of life. Is that the privilege of having somewhere to self-isolate to or does it come with having an introverted personality? Before quarantine, many would perceive me as a mild-mannered individual. I ask a lot of questions. I guess that’s where my affinity for journalism comes from. Yet, in a global crisis, not much has changed. For someone that suffers from anxiety, one would think I would have more emotional unrest during the worst public health crisis in a generation. But no. I’m content, staying at home.

Whilst this pandemic has been liberating for me, it has shown how much privilege I still have despite being at three disadvantages in society: the colour of my skin, my invisible disability and being an introvert in a world designed for extroverts. Yet, cabin fever does set in once in a blue moon and sometimes it does feel like Groundhog Day. Despite being at comfort in my own space, my concept of time is being challenged. Like, what is a weekend? Not even Bill Murray can save me from this paradox. Not my books, nor Disney+ subscription, films, or The Doctor, Martha and that fogwatch.

What I hate about being an introvert in the buzz term of today – “unprecedented times” – is how I’m not suffering like my extroverted friends. Perhaps this is what it means to live in society designed to accommodate you. The world outside of a health crisis – is this what it’s like? Imagine if I also happened to be an able-bodied, White, straight man as well? Just imagine. Today, extroverts are suffering. Ambiverts are suffering. When this is over will we see an increase in agoraphobia?

And in a society where extroverts are privileged over introverts, the outgoing outspoken marketing professional is valued more than the introverted, reclusive schoolteacher.

Yet, today, we are seeing the value of nurses, doctors, teachers, lecturers / academics and so forth. Many of whom will be introverts going against the grain of what feels normal to them. The person seen to be outgoing and talking and networking is regarded as a team player, in comparison to the freelance blogger or journalist writing away on their computer at home. Many of my teacher friends that talk for a living also love to recluse in their homes, as drinking your own drinks and eating your own food in your own house is great. Can you hear the silence, the world in mute? Priceless.

In my job, I recall in the training we did the Myers-Briggs test in order to get to know each other better. Safe to say I was 97% introvert, which had increased somewhat since I was a student. Coincidence, I think not. In a job where I also go to meetings for a living, and network and people (if I can make a verb out of people), it can be draining. The meetings, the networking, the small talk, the different hats and masks people wear.

As awful as Coronavirus is, I will go back to my intro in saying that this new pace of life is almost like a dream, with intermittent periods of cabin fever. I can recharge my life batteries when I want. I can be alone when I want. I can read, watch films and television series when I want. I like to engage in activities that require critical thought. Self-isolation has given ample time for that. And good things have come from my introspection. Moreover, many conversations with myself. No, I’m not Bilbo Baggins. However, to talk with oneself is freeing. It’s the first sign of intelligence, don’t ya know?

But self-isolation to me and many of my introvert colleagues, it’s our normal. Social distancing is a farce because we are still being social. “Physical distancing” is a better term. Not in this era of WhatsApp, Instagram and Zoom, we’ve never been more social. Coronavirus has shown us a social solidarity that I thought I would not see in my lifetime. To put it bluntly, Coronavirus has pretty much eliminated the quite British obsession of small talk, and given me opportune moments to think.

Whilst my extrovert colleagues want to have that picnic in the park, I’m quite happy to sit in the garden. There lies another privilege. Simultaneously, I seldom feel the need to go out. Where I miss my cinema trips, I remember Netflix, Amazon Prime, Britbox and Disney+. Sure they’re not IMAX but they’ll do. I miss the pub but there’s the supermarket with all sorts of choices of IPA to choose from. Indeed, I have found solace in having my access stripped right back. The freedom to choose afforded to me because I work and live in a “developed country” (I use this term loosely).

For those of us that live in Britain, Coronavirus has swiftly shown that we live in a first-world country with a third-world healthcare system and levels of poverty – highly-skilled medical professionals in a perilously underfunded NHS systematically cut for the last ten years by the Tories.

Unlike University, I can mute social media for a couple of hours, and do some reading. I hate that I am so comfortable, whilst others are not. I often think about international students shafted by visa issues, and rough sleepers who don’t have the privilege of thinking about self-isolation. What about those having to self-isolate in tower blocks like Grenfell? What if we were to have another tragedy like Grenfell during a public health crisis? I hate how Coronavirus has exposed underlying inequalities, and how after this, these systems of power will likely carry on like it’s business as usual.

I don’t feel defeated or bored but the other inequalities in society do make me worry. Having been a victim of racism ten times over, both by individuals and institutions, I know that racism is its own disease and it won’t simply go on holiday because we’re in a pandemic. I know increasing police powers will disproportionately impact people from Black backgrounds, especially in working-class communities, but as Black people (pre-Coronavirus) at a rate of nine times more likely to be stopped and searched than a White person in Northamptonshire is bad enough, isn’t it?

This solitude has pushed me creatively with my poetry and own blogs. Take Eric Arthur Blair, or George Orwell as he was known; when he was sick with TB, he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. The book we now lord about today is essentially a first draft. Rushed. A last bout before death. In my isolation, I’m excited for the number of dystopian texts that will come out of Coronavirus, particularly political narratives on how Britain and America reacted. I’m looking forward to artistic expression and if the British public will hold the Government to account. One could argue their thoughtlessness, and support of genocide (herd immunity) is a state crime.

Whilst it is easy to blame the Chinese government, our own government have a lot to answer for and metaphorically speaking, someone (or quite a few people) need to hang.

A good friend and confidant has implored me to write a book as a project. Being naturally inward in my personality, I could do it. Though, I have my reservations. Perhaps I could write a work of genius that goes on to define a generation. Nonetheless, I observe that during lockdowns around the world, there will be both introverts and extroverts applying their minds to art and creativity. Writing books. Painting pictures. Discovering theories, like Isaac Newton did when he was “confined” to his estate during the Plague in 1665.

One day the curve will flatten: we will see each other again at the rising of the sun, folks say we must make use of this time; however, this is unprecedented, so it is also perfectly okay to be at peace with your loved ones, cherish those moments, and do absolutely nothing of consequence at all.

What’s in the future for criminology?

This year marks 20 years that we have been offering criminology at the University of Northampton and understandably it has made us reflect and consider the direction of the discipline. In general, criminology has always been a broad theoretical discipline that allows people to engage in various ways to talk about crime. Since the early days when Garofalo coined the term criminology (still open to debate!) there have been 106 years of different interpretations of the term.

Originally criminology focused on philosophical ideas around personal responsibility and free will. Western societies at the time were rapidly evolving into something new that unsettled its citizens. Urbanisation meant that people felt out of place in a society where industrialisation had made the pace of life fast and the demands even greater. These societies engaged in a relentless global competition that in the 20th century led into two wars. The biggest regret for criminology at the time, was/is that most criminologists did not identify the inherent criminality in war and the destruction they imbued, including genocide.

In the ashes of war in the 20th century, criminology became more aware that criminality goes beyond individual responsibility. Social movements identified that not all citizens are equal with half the population seeking suffrage and social rights. It was at the time the influence of sociology that challenged the legitimacy of justice and the importance of human rights. In pure criminological terms, a woman who throws a brick at a window for the sake of rights is a crime, but one that is arguably provoked by a society that legitimises inequality and exclusion. Under that gaze what can be regarded as the highest crime?

Criminologists do not always agree on the parameters of their discipline and there is not always consensus about the nature of the discipline itself. There are those who see criminology as a social science, looking at the bigger picture of crime and those who see it as a humanity, a looser collective of areas that explore crime in different guises. Neither of these perspectives are more important than the other, but they demonstrate the interesting position criminology rests in. The lack of rigidity allows for new areas of exploration to become part of it, like victimology did in the 1960s onwards, to the more scientific forensic and cyber types of criminology that emerged in the new millennium.

In the last 20 years at Northampton we have managed to take onboard these big, small, individual and collective responses to crime into the curriculum. Our reflections on the nature of criminology as balancing different perspectives providing a multi-disciplinary approach to answering (or attempting to, at least) what crime is and what criminology is all about. One thing for certain, criminology can reflect and expand on issues in a multiplicity of ways. For example, at the beginning of 21st terrorism emerged as a global crime following 9/11. This event prompted some of the current criminological debates.

So, what is the future of criminology? Current discourses are moving the discipline in new ways. The environment and the need for its protection has emerge as a new criminological direction. The movement of people and the criminalisation of refugees and other migrants is another. Trans rights is another civil rights issue to consider. There are also more and more calls for moving the debates more globally, away from a purely Westernised perspective. Deconstructing what is crime, by accommodating transnational ideas and including more colleagues from non-westernised criminological traditions, seem likely to be burning issues that we shall be discussing in the next decade. Whatever the future hold there is never a dull moment with criminology.

20 years of Criminology

It was at the start of a new millennium that people worried about what the so-called millennium will do to our lives. The fear was that the bug will usher a new dark age where technology will be lost. Whilst the impending Armageddon never happened, the University College Northampton, as the University of Northampton was called then, was preparing to welcome the first cohort of Criminology students.

The first cohort of students joined us in September 2000 and since then 20 years of cohorts have joined since. During these years we have seen the rise of University fees, the expansion of the internet and google search and of course the emergence of social media. The original award was focused on sociolegal aspects, predominantly the sociology of deviance, whilst in the years since the changes demonstrate the departmental and the disciplinary changes that have happened.

Early on, as criminology was beginning to find its voice institutionally, the team developed two rules that have since defined the focus of the discipline. The first is that the subject will be taught in a multi-disciplinary approach, widely inclusive of all the main disciplines involved in the study of crime; so alongside sociology, you will find psychology, law, history, philosophy to name but a few. The impetus was to present these disciplines on an equal footing and providing opportunity to those joining the course, to discover their own voice in criminology. The second rule was to give the students the opportunity to explore contentious topics and draw their own perspective. Since the first year of running it, these rules have become the bedrock of UoN Criminology.

The course since the early years has grown and gone through all those developmental stages, childhood, adolescence and now eventually we have reached adulthood. During these stages, we managed to forge a distinctiveness of what criminology looks like; introducing for example a research placement to allow the students to explore the theory in practice. In later years we created courses that reflect Criminology in the 21st Century always relating to the big questions and forever arming learners with the skills to ask the impossible questions.

Through all these years students join with an interest in studying crime and by the time they leave us, to move onto the next chapter of their lives, they have become hard core criminologists. This is always something that we consider one of the course’s greatest contribution to the local community.

In an ordinary day, like any other day in the local court one may see an usher, next to a probation officer, next to a police officer, next to a drugs rehabilitation officer, all of them our graduates making up the local criminal justice system. A demonstration of the reach and the importance of the university as an institution and the services it provides to the local community. More recently we developed a module that we teach in prison comprised by university and prison students. This is a clear sign of the maturity and the journey we have done so far…

As the 21st century entered, twin towers fell, bus and tube trains exploded, consequent wars were made, riots in the capital, the banking crisis, the austerity, bridge attacks, Brexit, extinction rebellion, buildings burning, planes coming down, forest fires and #metoo, and we just barely cover 20 years. These and many more events keep criminological discourse relevant, increase the profile of the subject and most importantly further the conversation we are having in our society as to where we are heading.

As I raise my glass to salute the first 20 years of Criminology at the University of Northampton, I am confident that the next 20 years will be even more exciting. For those who have been with us so far a massive thank you, for those to come we are looking forward to discussing some of the many issues with you. We are passionate about criminology and we want you to infect you with our passion.

As they say in prison, the first 20 years are difficult the rest you just glide through…

Is unconscious bias a many-headed monster?

When I was fourteen, I was stopped and searched in broad daylight. I was wearing my immaculate (private) school uniform – tie, blazer, shoes… the works. The idea I went to private school shouldn’t matter, but with that label comes an element of “social class.” But racial profiling doesn’t see class. And I remember being one of those students who was very proud of his uniform. And in cricket matches, we were all dressed well. I remember there being a school pride to adhere to and when we played away, we were representing the school and its reputation that had taken years to build. And within those walls of these private schools, there was a house pride.

Yet when I was stopped, it smeared a dark mark against the pride I had. I was a child. Innocent. If it can happen to me – as a child – unthreatening – it can really happen to anyone and there’s nothing they can to stop it. Here I saw unconscious bias rear its ugly head, like a hydra – a many-headed monster (you have to admire the Greeks, you’re never stuck for a metaphor!)

If we’re to talk about unconscious bias, we must say that it only sees the surface level. It doesn’t see my BA Creative Writing nor would it see that I work at a university. But unconscious bias does see Black men in hoodies as “trouble” and it labels Black women expressing themselves as “angry.”

Unconscious bias forces people of colour to censor their dress code – to not wear Nike or Adidas in public out of fear that it increases your chances of being racially profiled. Unconscious bias pushes Black and Asians to code-switch. If a White person speaks slang, it’s cool. When we do it, it’s ghetto. That’s how I grew up and when I speak well, I’ve had responses such as “What good English you speak.” Doomed if you do, doomed if you don’t.

How you speak, what you wear – all these things are scrutinised more when you don’t have White Privilege. And being educated doesn’t shield non-White people (British people of colour included) from racist and xenophobic attacks, as author Reni Eddo-Lodge says in her book:

“Children of immigrants are often assured by well-meaning parents that educational access to the middle classes can absolve them from racism. We are told to work hard, go to a good university, and get a good job.”

The police can stop and question you at any time. The search comes into play, depending on the scenario. But when I was growing up, my parents gave me The Talk – on how Black people can get hassled by police. For me, I remember my parents sitting me down at ten years old. That at some point, you could be stopped and searched at any time – from aimlessly standing on a street corner, to playing in the park. Because you are Black, you are self-analysing your every move. Every footstep, every breath.

And to be stopped and searched is to have your dignity discarded in minutes. When it happened, the officer called me Boy – like Boy was my name – hello Mr Jim Crow – like he was an overseer and I was a slave – hands blistering in cotton fields – in the thick of southern summertime heat. Call me Boy. Call me Thug. No, Call me Target. No, slave. Yes master, no master, whatever you say master. This was not Mississippi, Selma or Spanish Town – this was Northamptonshire in the 2000s and my name is Tré.

Yes, Northamptonshire. And here in 2019, the statistics are damning. Depending on which Black background you look at, you are between six and thirteen times more likely to be stop and searched if you are Black than if you are White (British). And reading these statistics is an indication of conversations we need to be having – that there is a difference between a Black encounter with the police and a White encounter. And should we be discussing the relationship between White Privilege and unconscious bias?

Are these two things an overspill of colonialism? Are they tied up in race politics and how we think about race?

Whilst these statistics are for Northamptonshire, it wouldn’t be controversial to say that stop and search is a universal narrative for Black people in Europe and the Americas. Whether we’re talking about being stopped by police on the street or being pressed for papers in 1780s Georgia. Just to live out your existence; for many its tiring – same story, different era.

You are between six and thirteen times more likely to be stopped if you are Black than if you are White (British) – but you know… let’s give Northamptonshire police tasers and see what happens. Ahem.

Bibliography

Eddo-Lodge, Reni. Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018. Print