Home » Articles posted by Tré Ventour-Griffiths (Page 7)

Author Archives: Tré Ventour-Griffiths

We cannot allow 'Windrush Lessons Learned' to be buried by CORONAVIRUS

When my grandparents and great-grandparents came to this country between 1958 and 1961, they came here under the Nationality Act (1948) as British citizens. It’s by some miracle that my grandparents were not sucked into the Windrush Scandal, members of a generation that saved Britain by filling in its labour shortages after the War. However, we cannot measure immigration simply in gross domestic product [GDP]. There is a human case to be made for immigration, including the Windrush Generation, who have contributed more to this country than just labour, including to the social history too. That the Windrush Scandal is as much a slight on the Windrush (1948 – 1973) as it is to their descendants, including Black British people that see themselves as much British as they are West Indian.

These descendants of slaves were now being sent back to the places their ancestors toiled, whom the British kidnapped from the African continent against their will. That my ancestors came to be in the Caribbean at the end of a sword.

(Legacies of British Slave-ownership, UCL)

In 2018, MP David Lammy addressed the House on what became known as the Windrush Scandal; on why and how Black British citizens, members of this Windrush Generation were being detained and deported, denied their pensions, healthcare and losing their jobs – many of whom had been in this country since they were young children. Wendy Williams’ Windrush Lessons Learned depicts issues that go way beyond the Scandal.

In the Home Office, Lessons Learned shows a department not fit for purpose after institutional failures within government as well as a lack of understanding of Britain’s colonial history. Like in higher education, it showed an ignorance towards race issues that run parallel to the definition of institutional racism in The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry (1999).

After reading the report (somewhat), it feels that this is another tickbox exercise. Whilst the report does talk about the victims of institutional violence at the hands of government, it leads me to believe that the recommendations will remain as such, recommendations. That whilst students are challenging higher education to decolonise, the same must be done for government. The sincerity of Priti Patel’s apology is flimsy at best and most of the Windrush victims have still yet to be compensated properly.

People have died at the hands of the Conservative government’s hostile environment and this document comes at a time where Britain is in the thick of the worst health pandemic in a generation. To release this now when everyone is preoccupied is a testament to how the government feels about the victims. The fact that this document cannot be debated in parliament properly and scrutinised because of COVID-19. The Home Office have ticked their boxes and the victims will be no better off in the end.

Whilst the government implementing future policies to prevent things like this happening in the future would be a good thing, policies can be just policies in the same vain that recommendations can simply sit as recommendations.

If nobody is there to enforce policies; if we have politicians advocating for social cleansing; if we have eugenicist MPs making decisions; if we use terms like “herd immunity” but in reality that is a genocidal ideology… what hope is there for the Windrush Generation, whom also make up part of the population the government is willing to throw under the bus to fight coronavirus? Have lessons really being learned when Boris and company are willing to play colonialism again with its current population?

This Conservative government, particularly its promotion of eugenicist views, and Priti Patel’s tenure as Home Secretary have shown that they can no longer be a leader on human rights. The review shows a government that does not care about you unless you are a White British, with English as your first language, in other words depicting an image of quintessential “Englishness.” Splitting children from the families is not just the work of Uncle Sam, nor does deportation simply hurt the deportees.

This crisis should make us challenge what Britishness looks like and that we need to be careful who we call immigrants because the Black Man (and Woman) have been on these shores longer than the White Man (and Woman) – the Angle, the Saxon, the Jute, the Norman… longer than what denotes Englishness in the national conscience. Yet, indigenousness has been stamped on whiteness, but foreigner – interloper – immigrant – follows blackness / brownness, which in my opinion is much ado with the lapses of historical knowledge of British history in wider society.

However, wasn’t it Africans, or as they were, “The Moors”, who stood watch on Hadrian’s Wall for nearly 350 years?

Wendy Williams wants to press reset on the Home Office, changing a toxic working culture into a positive less defensive department with a new mission statement, a department that doesn’t treat criticism as a crime. She pushes for a department that gives whistleblowers protection. Diversity should be celebrated, not revered and a workforce to undergo training on Britain’s colonial history, migration and how Black Britons came to be here. In short, Williams wants to Decolonise the Home Office. Good.

The report stops short of calling the Home Office institutionally racist. Yet, the treatment of the Windrush Generation cannot be argued to be anything but. An inquiry needs to be led into why the Home Office have repeatedly discriminated against British communities from Black, Asian and other marginalised ethnic backgrounds. The report tells us that the Windrush Scandal was no accident. It’s just another example of how institutions get away with murder (literally), in the tint of Grenfell and Hillsborough, victims still long for justice and these structures continue to give lip service.

Priti Patel’s apology is offensive. I take it with a grain of salt. For someone who is actively a racism denier, I cannot take anything she says seriously. The apology is to make people feel at ease, not a declaration of empathy from a feeling of guilt. Skin folk ain’t kin folk; she is a collaborator, one of the many people of colour recruited to hold up White Power. She is a bigot and no better than Mogg, Cummings, and the prime minister himself.

Deeds not words; if they wants to show they care, dismantle those hostile environment policies and initiate a root-and-branch independent investigation into racism in the Home Office – until that day arrives , words are just words.

10 Things I Want to Say to Jane Austen

I

Why are you the go-to of all the women writers in history?

II

It’s so hard to cut through the whiteness of your novels. The ongoing enduring whiteness pontificating, reflected in almost all English literary canon. Not impressed.

III

Your books have no heroes or villains that look like me, despite you living in a time where you shared these British streets and roads with the Black Georgians.

IV

Thank God for Andrew Davies’ re-imagining of your unfinished Sanditon. I loved Miss Lambe! #BlackExcellence

V

George Wickham is a wasteman.

VI

Seeing Black people portrayed as actual human beings in a period drama [Sanditon] put butterflies in my stomach. Any time I saw them, I was smiling for a week. With their natural hair as well… truths universally acknowledged and all that #fightme #BlackistheNewWhite

VII

When you see these characters, you remember every detail. You recall it as memory, as a a vivid as a ballroom dance – corsets, violins and the flesh Mother Africa.

VIII

Why couldn’t you have characters like Rhoda Schwartz or Sam from Vanity Fair by Thackeray? #ohshityoudeadthen

IX

If you were around today, you’d be unstoppable on Twitter with your idealised femininity and blinding whiteness. You’d be what they call an influencer #wokeAF #edgelord

X

Badly Done, Jane.

Why do HEIs task diversity leads with solving systemic issues?

“While it is of utmost importance that universities reflect the demographic diversity of the societies they are supposed to serve, the question of demographic diversity falls short of addressing the question of decolonisation.”

(Icaza and Vázquez, 2018: 115).

When equality, diversity, inclusion work is left to a few good eggs in our universities, there is a problem. Hiring EDI leads will not make your institution less racist, sexist, ableist, homophobic or transphobic. Equity must be part of how a company hires and makes decisions, and that goes to to the very top of any establishment. From healthcare to policing and education, public and private bodies claim equality, diversity and inclusion is a priority. However, there is a gap between what institutions say, and do.

Diversity officers, equality leads, and roles with “BME” and “BAME” in their titles are blue plasters for what is essentially a tumour. Whilst I recognise these roles need to exist, EDI and race equity should be in the main objectives and KPIs of all universities. Decolonisation needs to run hand-in-hand with diversity work, and whilst universities give lip service to EDI while simultaneously not engaging in decolonial projects, what you’re telling the victims of colonisation is you don’t belong here.

Colonisation, and then its flip, decolonisation, is systemic and far-reaching. To hire an individual (singular) in these roles, often on a part-time basis to tackle systemic problems is both short-sighted and cruel. There is no quick-fix to say, institutional racism, and it’s everyone’s responsibility.

Having attended conferences ostensibly focused on racism, it is evident another profound challenge to higher education is a reluctance from institutions to talk about race – and to implement race equity as a separate division to generic EDI practice. Under race, we have: whiteness, White Privilege and (race-specific) unconscious bias, as well as identity politics impacting the life experiences of people of colour. What the African-American cultural theorist W. E. B DuBois (1903: 2) called “double consciousness,” and more recently with Afua Hirsch (2018) in Brit(ish).

Universities need to support student campaigns for race equity and diversity, including student union initiatives around decolonisation (and blacktivism) in response to national (and global) narratives, as political activism is one of the movements pushing for a more equal and fair society.

Consistently, Britain’s national response to race issues has swayed from varying degrees of reluctance to negligence and this is no more evident than in the education sector. Britain’s response to discussing its colonial past is what Shashi Tharoor called “historical amnesia” (Independent) and “today’s student movements are confronting universities with their colonial histories […] of segregation […] and the recognition of the universities’ own participation in the modern/colonial order” (Icaza and Vásquez, 2018: 122).

HEIs need to support campaigns, including those around decolonising education (and blacktivism) regardless of their source. Icaza and Vásquez discuss decoloniality as a conduit to seeing “the dynamics of power differences, social exclusion and discrimination” in relation to inequality under the umbrella of race, gender, and socioeconomic deprivation (2018: 113). Whilst their research centres on Amsterdam, contemporary Britain, is also built in the ruins of empire.When White, able-bodied heterosexual male is the default in a heteronormative society, it is safe to presume the same occurs in HE. After all, universities as with all British institutions, are part of society and thus cannot escape the same colonising imperatives.

Elite universities, such as Oxford, have been scrutinised for their part in British colonial history. The Academy was built to exclude people who were not White, rich, male, able-bodied and straight, ensuring that minorities often find themselves scaling the walls into The University.

Student equality, or lack of, can be seen reflected in those teaching them on a day-to-day basis. To feel equal in the classroom, one focal point of conversation is the lack of role models – the deficit of professors in HE to be like, from varied diasporic African and Asian backgrounds.

In the Equality in higher education: statistical report 2018, Advance HE stated only 85 Black professors work at British universities (in relation to over 10,000 White). This statistic is an indictment on the lack of visibility at the very top of academia, and representation needs to extend further than race to also include disability, sexuality and religion. It is about seeing your story in those that have gone through it before, to show the next generation of potential leaders and academics it is possible.

Whilst efforts to make universities more inclusive have been implemented through initiatives like decolonising the curriculum this is a drop in the ocean in terms of diversifying the workforce, including senior management teams (Icaza and Vásquez, 2018: 115). To reach the fullest potential of diversity in HE it is essential to have as many nonnormative voices as possible in the decision-making processes. In including them, we can then more openly critique what knowledge is being produced, how it is being produced and what’s being created. How it is implemented directly impacts student equality and how they feel included in their university community:

“The implications of this whiteness and Eurocentrism go beyond history. This state of affairs mediates our whole education experiences considerably, so much so that attempting to study anything outside of the white and Eurocentric requires going the extra mile.”

Ore, 2019: 56

For race equity, especially in a student body as culturally diverse as at Northampton, it is important to consider whether the continuing use of homogeneous groups for minorities, such as BAME [Black Asian Minority Ethnic] inculcates equality or creates further division. Certainly such homogenisation inherently excludes discourses of intersectionality so necessary in ensuring equity. When universities enrol these students, it is imperative to consider if there are ample, appropriate support systems in place – from race equity to working class, sexuality and disability.

Across the sector, the dropout rate of specifically Black students is high, and one would think there would be support prevention systems to reduce the number of drop outs. At UK universities, Black students are 50% more likely to drop out than their Asian colleagues and one in ten Black students drop out, in comparison to 6.9% of all students – according to the University Partnership Programme, Social Market Foundations (Adegoke, 2019: 32-33).

Goldsmith’s Dr Nicola Rollock, for instance, believes not enough is done to investigate the cause and believes there’s a fear of talking about race in the sector:

“My concern is that these issues aren’t look at in any fundamental way: when they are, all black ethnic groups are amalgamated into one mass, and they shouldn’t be. The data doesn’t speak to distinct differences. And there’s also a fear of talking about race. If they’re talking about black and minority ethnic students, race needs to be a fundamental part of the conversation, but I would argue that as a society, and […] within education policy, race is a taboo subject” (Rollock, 2019, quoted in Adegoke, 2019: 34).

For a university as culturally diverse as Northampton (as far as students are concerned), is it right to put people into homogeneous groups, like BAME? Is there equity in grouping this way? Why are students not born into White Privilege amalgamated into one mass? Why is there a fear of talking about race in classroom but also in wider society? What if they were lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, as well as from the African or Asian continents?

Do HEIs have ample support systems in place – from race, gender to sexuality and disability? Moreover, universities often think it is enough to have more Black people in the building. Emotional labour is not something higher education institutions think about (Adegoke, 2019: 33).

What providers can do is engage with national reports, including the Race Equality Charter (REC) – but also 2017’s Lammy Review, and the 1999 Macpherson Report (both focused on the criminal justice system but no less relevant to universities) – and research into LGBTQ+ experiences in higher education, as shown in Education Beyond the Straight and Narrow by the National Union for Students [NUS].

Where universities see equality, diversity and inclusion work as a legal requirement under the Equality Act (2010), important and vital discussions around ethics and moral duty need to happen as well. Where HEIs often think about the money, there is a human case to be made for students!

When EDI is seen as an add-on to general practice, it can often be viewed as a “tick-box exercise.” It can frequently have an image of transitioning or adaptation, often describing “their missions by drawing on the languages of diversity as well as equality” (Ahmed, 2018: 333). Diversity should be the default setting but hiring people with BME, BAME, diversity, equality or inclusion in their title is simply a blue plaster for what is a far-reaching nasty tumour. To do diversity work, you must do decolonial work.

So, really, higher education institutions need to be thinking about how the emotional labour of equality and diversity work impacts their employees, especially women of colour.

Referencing

Acciari, L (2014). ‘Education Beyond the Straight and Narrow,’ nus.org, [online]. Available from: https://www.nus.org.uk/global/lgbt-research.pdf [Last accessed 30 December 2019]

Adegoke, Y and Uviebinené, E. (2019). Slay in Your Lane. London: 4th Estate.

Advance HE (2018). ‘Equality in higher education: statistical report 2018,’ ecu.ac.uk, [online]. Available from: https://www.ecu.ac.uk/publications/equality-higher-education-statistical-report-2018/ [Last accessed 30 December 2019]

Ahmed, S. (2018). Rocking the Boat: Women of Colour as Diversity Workers. In: Arday, J., Mirza, S. (eds). Dismantling Race in Higher Education: Racism, Whiteness and Decolonising the Academy. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 331 –348.

Bhopal, Kalwant (2018), ‘The Persistence of White Privilege in Higher Education: Isn’t it Time for Radical Change?,’ Social Sciences Birmingham, [online]. Available from: https://blog.bham.ac.uk/socialsciencesbirmingham/2018/05/24/the-persistence-of-white-privilege-in-highereducation-isnt-it-time-for-radical-change/ [Last accessed 30 December 2019]

Broomfield, Matt (2017) Britons suffer ‘historical amnesia’ over atrocities of their former empire, says author. Independent [online]. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/shashi-tharoorbritain-india-suffer-historical-amnesia-over-atrocities-of-their-former-empire-says-a7612086.html [Last accessed: 31 December 2019]

Bulman, May (2017) Black students 50% more likely to drop out of university, new figures reveal. Independent [online]. Available from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/black-students-drop-outuniversity-figures-a7847731.html [Last Accessed: 31st December]

DuBois, W. E. B. (1994). The Souls of Black Folk. Dover Edition. New York: Dover Publications. Inc

Equality Act 2010. London: TSO.

Fanon, F. (1967). Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

Hirsch, A (2018). Brit(ish). London: Vintage.

Home Office. (1999). The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. (Chairperson: William Macpherson). London: TSO.

Icaza, R., Vásquez, R. (2018). Diversity or Decolonisation? In: Bhambra, G. K., Gerbrial, D., Nişancioğlu, K. (eds). Decolonising the University. London: Pluto Press, pp. 108 – 128.

Kwakye, C and Ogunbiyi, O. (2019). Taking Up Space. London: Merky Books.

Lawton, Georgina (2018). Why do black students quit university more often than their white peers? The Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2018/jan/17/why-do-blackstudents-quit-university-more-often-than-white-peers [Last accessed: December 31 2019]

Lodge-Eddo, R. (2017). Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. London: Bloomsbury.

Ministry of Justice (2017). The Lammy Review. (Chairperson: David Lammy MP). London: TSO.

Social Market Foundation (2017) SMF and the UPP Foundation to investigate continuation rates in higher education in London. smf.co.uk [online]. Available from: http://www.smf.co.uk/smf-upp-foundationinvestigate-continuation-rates-higher-education-london/ [Last Accessed: 31 December 2019]

Social Market Foundation with University Partnership Programme (2017). ‘On course for success? Student retention at university,’ smf.co.uk [online]. Available from: http://www.smf.co.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2017/07/UPP-final-report.pdf [Last accessed: 31 December 2019]

If universities are serious about decolonisation, why do they continue with BAME?

One thing I’ve noticed in my term at the Student Union but working with university departments and staff, and going to other universities, is how many different terms there is to describe people who do not happen to be born into the comfort of White Privilege. At the University of Northampton, this demographic of students are the majority, so why refer to them as ethnic minorities? We are also the global majority. However, the term “ethnic minority” is only in reference to when take into account the colonial borders that divide us. And in my role at the Union, I had no say in the naming of this role, since it was before my time.

Yet, it is a trend at universities that we have White senior leaderships speaking for what I will refer into this post as the global majority. This very European paternalism in the tint of Out of Africa, Passage to India, and Boris Johnson reciting the lines to Kipling’s Mandalay in Burma! In the public and private sector, we have many acronyms and initialisms and seldom are they properly thought out. i.e BAME / BME. Not only are these terms not widely understood by those they are about (i.e students), they also homogenise identities that don’t happen to be White Anglo-European.

“BAME” [Black, Asian, Minority, Ethnic] and “BME” [Black and Minority Ethnic] are commonly used by public bodies, including the education sector, policing and the health service when referring to the global majority. These are not household terms and you don’t know unless you know.

People of Irish heritage in the Traveller communities are also supposedly included within the acronym too; not including them in the overall term is astounding, as they are some of the most marginalised groups in the country.

With the term “BME” in my job title, I admit it is extremely ironic that I disagree with it. I do not see myself ethnically as BAME or BME, and don’t particularly like it when staff describe students in this way, or even members of staff. What ever happened to individuality? I am a very proud British man of Grenadian and Jamaican descent. In this homogenisation, higher education institutions are disregarding individuals’ cultural heritage. It’s really unacceptable, and at universities, it has often been used as term interchangeably for Black students. And even Black, is not a homogenous. Race is nuanced, and identity politics, nuanced, further still.

Furthermore, “non-White” is problematic, still showing that we only exist as an extension of whiteness. Moreover, the term “people of colour”, it’s not a homogeneous group; skin folk ain’t kin folk and diversity doesn’t equal representation

Do we say non-Black when referring to White people? No, as “to be white is to be human; to be white is universal; I know this because I am not” (Eddo-Lodge, 2017). The term BAME / BME disregards geography and cultural heritage, the loaded histories of colonialism and the fact that my country, the country I was born and raised, colonised and enslaved my grandparents’ country. It ignores customs, traditions and language and that “anyone who isn’t white, all us brown-skinned immigrants from Far Far Away, we get lumped together and put in a drawer” (Boakye, 2019)

Whilst higher education institutions often give lip service to decolonial work, they continue to preach diversity and inclusion with terms like BAME, as “the words and terms we use to describe ourselves remain central to the ways we relate to our bodies. Certainly, if we want to set about work of decolonization we need to consider language” (Dabiri, 2019). Dabiri goes onto discuss the disparity between “cornrowing” (US English) and “canerowing” (Caribbean and British English) hair as a sad overhang of slavery. It could be argued that acronyms like BAME are a new brand of colonisation, keeping these Black and brown people in their place.

Universities know that they need to challenge the histories from which they were built. Just, are they a bit reluctant to do so? Yes. Is British traditionalism often standing in the way? Yes. We are living in the ruins of empire, and institutional racism is an overhang of that. And if academics and non-academics are using terminology that’s offensive and that people don’t understand, is it fit for purpose? Knowing what is appropriate language in discussions on race is the first step in this conversation.

If universities are serious about decolonisation, they need to look at more than just adding diverse authors to curricula!

Referencing

Boakye, J. (2019). Black, Listed. London: Dialogue Books.

Dabiri, E. (2019). Don’t Touch My Hair. London: Allen Lane.

Eddo-Lodge, R. (2017). Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. London: Bloomsbury.

Please Note

Any questions, email me at tre.ventour@northampton.ac.uk

I am a man and a brother: Black dignity in schools of White thought

Mom says “You have to work twice as hard for half of as much.” She means the odds are stacked against you if you aren’t a White, straight man. Even White women have to play the game. It’s episodes of Marvel’s Luke Cage like ‘Soliloquy of Chaos’ and ‘If it Ain’t Rough’, ‘It Ain’t Right. ‘It was Moment of Truth’ and ‘Manifest’. Or episodes of Jessica Jones like ‘AKA Sole Survivor’, ‘AKA I Want Your Cray Cray’, ‘AKA 1000 Cuts’. Oh, and ‘AKA Pray for My Patsy’. I could take some punches back then. Man, Jessica did too.

Mom and Dad talked about their grandparents but they also talked of slavery — Sam Sharp, Toussaint L’Ouverture, Nanny and the Maroons. They talked about Rosa Parks, Martin, Malcolm and Medger. They talked about people that lived life always on the offence. Back then I didn’t know enough about these people. Not slavery, America’s Civil Rights or the Windrush Generation. Stories that have been told and retold time and time again.

And in these stories there were Black martyrs but also Black villains. There were victims and guardians, like in Jordan Peele’s Get Out and the black in Black Panther. Yet, by the time I heard these stories, the narrative of Black insurrection against White power was set in stone. We speak of it always, as if it’s all we are — just people that don’t know how to smile.

But what of the Black middle-class against the Black working-class? It’s The Real Housewives of Atlanta staring into the faces of Top Boy, School Daze, Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk. And even there, division runs riot. The dark ones, the light ones — is it Naomi Campbell, Reni Eddo-Lodge and Akala or is it Viola Davis, David Harewood and Idris Elba? Or Lupita sticking it to Grazia on Twitter?

It doesn’t matter. I relate to all of them. I wander through our British cities. I relate to them in their own apartheid, the retelling of stories about race and racism in Britain, as most Black people I know have tales of punishment and pain.

Sometimes it’s about the subtleties in the workplace and at others, it’s racial violence, in an epilogue of Brixton ablaze and Enoch Powell. And the retelling of stories between people of colour is meditation. It’s inner peace that protects us, our souls at least. I was raised to talk. To tell stories.

As a Black person, I follow a set of unwritten codes (when talking to White people). Don’t walk too fast, don’t raise your voice… passion can be mistaken for anger. To be anti-White supremacy can be judged as anti-White or anti-Britain. To want to talk about colonialism can be seen as Black people just being bitter. And this is the dilemma of coming from immigrants from colonised countries, living in nations that did the colonising to begin with.

My cultural identity is in-part British, but it also swims in curry goat, calypso and reggae anthems. It’s in the stories of parties in my grandparents’ front room and grown folks liming to Candy at every. It’s cricket whites, Saturday rugby and match tea. And it’s my grandfather go-karting down the hills of St. George’s. These are the stories my parents carried, growing up in the late 80s early-90s but also in-part the memories my grandparents carried, ferried from the Grenada and Jamaica.

My cultural identity is macaroni cheese as a side dish, not a main course (blasphemy!). It’s curry chicken, rice and pigeon (or gungo peas) and veg in the Flora butter container. It’s plastic on the furniture and cups, glasses and plates that are just for show. But it is also church on Sunday’s, Catholic, something left behind in Grenada by the British. Something that became part of my grandparents, as they were taught to be British too — in all ways.

I grew up in the noughties, Northampton, educated at private schools around the shire. Prior to 2010, I was the only Black person at said schools and lived a boyhood that only acknowledged my existence in order to fetishize it — from comments about my skin colour to wandering white hands in vicinity of my afro hair. I had more of it back then.

I grew up quicker than what was natural. I saw thirteen-year-old White girls smuggle vodka cocktails into school in sports bottles. Imagine that! They called their parents unrepeatable names. I was around spoilt restless rich kids that had everything and didn’t appreciate its value. I was around people whose diction and vocabulary sounded like episodes of The Crown — Wolverton Splash, Scientia Potentia Est, and Paterfamilias, living it up like Prince Philip (Matt Smith) and Princess Margaret (Vanessa Kirby).

I recall thinking if I treated any of my family like that, I’d have been knocked so hard I’d be staring at my ancestors.

I was apprehensive about inviting friends home, people who had it all, with their many acres of land… judging our terraced house in town or my grandparents’ on a housing estate outside of Northampton. That anxiety stayed with me for most of a decade. It had the ability to expose the class divide between us… differences that didn’t go beyond the surface in class — the musical accents of my mother’s parents in the landscape of fried plantain, dumplings, and fish cakes laced in Scotch Bonnet pepper.

Explaining the nuances of growing up in a non-White British household is exhausting. It’s something that holds people of colour together but it also creates a double consciousness, sometimes triple, in terms of identity. “People of colour” aren’t a homogeneous group but some things we share.

And I’m British though. Mate. Innit. Can’t you tell?

There was a plurality in my existence, that one friend remarked on. She said “You’re lucky to be different and English is boring.” I had calypso in my walk but the Queen’s sceptre in my voice and sugarcane in my bones. And this identity crises, even at ten, made me feel three times my age (at least).

Like Lin Manuel Miranda says:

“I’m only nineteen but my mind is older”

My bitterness towards British private school culture now, looking back on my life, is just how traditional it was. I recall a recent conversation with a friend about cricket matches (a game that I love) but only now analysing how it was a tool of colonising. It got me thinking about my teachers and how they waltzed around corridors in capes, caps and gowns.

The houses, the brotherhoods, the fellowships and the sports matches and tournaments — it was all a bit Victorian. One school I went to, on its plaque, states Since 1595. Where were my family in 1595? Likely in the hulls of slave ships or on the lands of West Africa, oblivious to what was coming.

The schools I went to, many families reeked of old money, whose ancestors may have had interests in slave plantations or distant ancestor cousins that were officers in India or Burma. They could see I didn’t look like them but when someone said “But you’re not properly Black,” what they meant was, I wasn’t living on a council estate near Grenfell Tower. To be Black was to be poor… on drugs… suffering… a victim. Thief, slave, comedian… a caricature. Is this a truth universally acknowledged?

Safe to say, I was somewhat offended; and this revealed the crazy super-rich White fear towards poor Black people. Is this also another colonial trait, passed down through the centuries? This came from the mouths of people that swore by Rudyard Kipling and could probably recite the lines to Mandalay word perfect. I knew this wasn’t representative of White Culture but these were the people that we have to keep an eye on, the super-rich White racists. Men like Nigel Farage, who Russell Brand called “a poundshop Enoch Powell.” That made me chuckle but “we gotta watch him,” — as Brand puts.

What’s unique is that I see people like Farage and Mogg as products of the education system that made me.

But I came from estates and small houses where shoes were left at the door and where there was plastic on the furniture and monochrome photographs of my grandparents not long after they arrived in the UK. Times where, and still do, aunties and uncles and friends pass in and out of our houses. My grandparents’ front room / dining room is the shrine. It’s the Holy Grail and once upon a time, you could come without calling ahead.

Grandma tells me about how her mother, (my great-grandmother) would prepare soup every Saturday. Aunties, uncles, cousins, my uncle’s friends — everyone would turn up for a bowl. Black people, White people — and this was in the time of Britain’s No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs – there was still community in those small rooms of Bostock Avenue and she cooked extra.

In 2004, I we wore this ugly shamrock green blazer. They were Old England like Agatha Christie and Enid Blyton novels. It was coastal wrecks, horse-riding, and Summer Rig (an open-neck shirt in the summer). Why it was called Summer Rig is beyond me. Summer Rig was the most normal thing about schooling. It was the thing that placed that school in the land of the living, the land of society and civilisation, the land of real people of flesh and bone. Summer Rig was a cashpoint machine and a Mars bar. It was Pizza Hut, late brunch, Brits in Benidorm and Hyde Park Corner.

As a teenager, my relationship with myself centred around Britishness. My teenage years is when I was politicised. Thanks Auntie Luisa! I began to see myself as British first, and Black second and now I see myself as equally both. But my pet peeve is “You don’t look British” — since Britishness has been whitewashed. Britishness is not a pigment. I would argue it’s an ideology, a state of mind, more to do with identity than anything else. I’ve had “nice for a Black boy” — I’ve had “nigger” and “Go back to the trees you came from” — and “Has your dad been to prison?”

That last one was straight up cold! But it is in-part thanks to our racist media, or what Chimimanda Ngozi Adichie, in her TED Talk calls “The Danger of the Single Story.”

Belonging, to me, is a psychological process. It can be about race and class. But my own narrative was more about finding people who share like-interests. And I have spent many years trying to find those people, doing my best trying not to comply with the needs of the rest of society. I have even relegated myself to tick boxes. Will you accept me if I don’t talk about arts or politics? And instead, talk about gossip media and things I don’t care about? That if I perched on the end of the bench and remained invisible, that if I became like Harry, the boy under the stairs, will you accept me?

And aspiring to the culture of the super-rich of my youth, I had neglected the other parts of myself. It required me to sever the links to calypso, steel drums and supporting the West Indies cricket team even though they’re shit! Haha!

Look at the child I could have been if I didn’t scour the Earth for validation. It was being told Christopher Columbus accidentally discovered the Americas and the West Indies looking for India, by a White teacher despite the Arawak, Carib and Amerindian peoples living there before he arrived.

It’s that nothing exists until the European discovers it. And that my heritage is forever being whitesplained to me by White people that claim to know it better than I do…

Through having my existence contested, I learned how to smile, at the titles of those episodes like footnotes to the past. I smile at them like how my school had coined a term for an open-necked shirt. “Summer Rig” , capitalised, hilarious. That my experience was valid because it’s mine, sticking it to The Man. It meant growing up in a multiverse of childhoods.

My first coming-of-age was listening to the stories of my ancestors; the second coming-of-age was writing my own.

Daredevil taught me forgiveness

Until just before starting university I held anger for a certain member of my family. Throughout my life, this person and I had always been at odds and when I was around fifteen years old, I decided to cut this person loose. I did not speak to them again for nearly three years, much to the pain of my relatives.

In the April of 2015, the maiden season of Daredevil premiered on Netflix. Based on the Marvel Comics by Stan Lee and Bill Everett, it follows Matthew Murdoch (Charlie Cox), a blind lawyer by day and a costumed vigilante by night. With the theme of forgiveness running through season one, he is also a Catholic, whilst he beats bad people to within an inch of their lives!

Watching Matt in pits of Hell’s Kitchen showed me the darkness I held in my heart. You can forgive but never ever forget. The weight we hold as human beings is ear-splitting. In Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, the characters are burdened with abstract things, including grief and guilt. We are only as human as we allow ourselves to be. In the film Just Mercy, in its final moments, Michael B. Jordan’s Bryan Stevenson states “we all need grace, we all need mercy.” The film also states 1 in 9 death row inmates are wrongfully convicted, and 165 have been exonerated since 1973.

What if Bryan Stevenson hadn’t shown mercy or grace to those committed to death row? Despite being imprisoned, they are still human beings, as Fyodor Dostoyevsky puts it:

“A society should be judged not by how it treats its outstanding citizens but by how it treats its criminals. The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons. If he has a conscience he will suffer for his mistake. That will be his punishment-as well as the prison.”

How human beings hold on to things can be a mental block to stepping forward or progression. In Disney’s Lion King, Rafiki says “Oh yes, the past can hurt. But you can either run from it, or learn from it.” And that stone in our stomachs hurts more when we hold on to stuff – for example me avoiding a single person for three years, and your world can shrink exponentially. Living a life looking over your shoulder is mentally draining.

But once you forgive, new roads can open; and in that moment, there is no past or future, just you in the present moment and an open road to the rest of your life.

The only business we have with the past is how we can learn from it. And watching Daredevil all those years ago is in-part responsible for the mild-mannered human being I am now. Murdoch seeing it as his Catholic duty to protect Hell’s Kitchen from those who would see it harm, tied with his mentor Father Lantom (Peter McRobbie) make for an excellent partnership.

Episode one starts with Matt in a confession booth with Father Lantom, and their conversations appear every so often throughout this show’s three-season run. “Nothing shines up a halo faster than death Matthew. But funerals are for the living… and revising history… only dilutes the lessons we should learn from it” says Lantom, and this will always ring true, so long as we humans continues to disregard history and make the same mistakes.

At eighteen, when you think you know everything and you really know nothing, I found Daredevil. Its exploration of forgiveness, mercy and grace in the tint of political violence, corruption, immorality and populist media. Its maiden season showed me how to forgive because its protagonist had every reason not to. This theme of mercy followed with Jessica Jones, Luke Cage and Iron First, as well The Punisher. All these characters loved and lost, and were betrayed, lives written in violence like mine had been.

And yet, these characters and this world saw looking with your eyes makes you blind, as there are other ways to see.

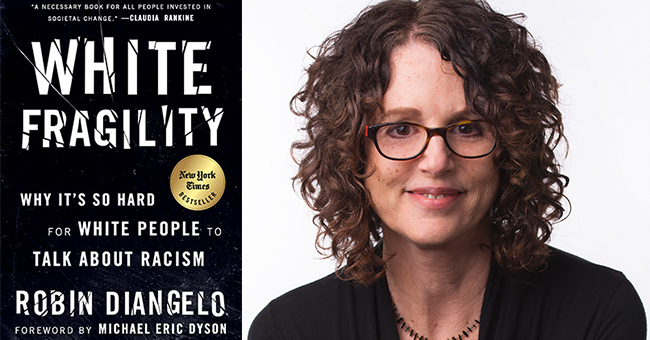

“When white women cry, Black men get hurt” – On ‘White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo

Once upon a time, if you spoke to British-born and raised White people they would have told you that everybody in this country was equal. Yet, Britain’s wealth and to a degree, identity, comes from slavery, empire and stolen land. Why Britain calls itself great comes from the toil and torture of enslaved Africans’ labour on plantations in America and the West Indies.

“Social justice warrior bullshit” is a term I have come across when speaking to White Anglo-Europeans online, foolishly engaging in online debates on race and racism. The fact that many of these trolls can’t seem to understand the barriers that face marginalised communities, and the more communities you fit into, the worst it can be. And the fact that Boris Johnson’s cabinet is the most diverse a cabinet has ever been is not progress. Diversity does not equal representation; and the Priti Patels of this world, who inhabit whiteness and use it to pull the ladder up from other localised disparities in terms of race. i.e increased powers in Section 60.

Reading White Fragility by sociologist Dr. Robin DiAngelo for the FBL Book Club (but open to all) – all the instances of White people not being able to talk about race mentioned in the text, I have seen at one point in my life or another. The classic is “I was raised to treat everyone equally” or “I don’t see colour”, and “I don’t care if you’re pink, purple, polka-dotted” and so forth.

One of the worst and most potent forms of White fragility is White people that think they understand racism because they have mixed-race children or relatives. The instinctive defensiveness is at every level of society; from the White working class that don’t feel “privileged” because they use food banks, universal credit or the benefits system to the I-have-a-Black-friend-community-so-I-can’t-be-complicit-in-White-supremacist structures sorts.

In her book, DiAngelo breaks whiteness down into layman’s terms. She deconstructs whiteness, White fragility and Privilege. How society is constructed is for the benefit of Whites. They are the default, so it’s White and the Rest; from the history we learn in schools to “flesh-coloured” plasters which fit the hue of Caucasians. Due to societal design, this also means they have a deficit of “racial stamina” to engage in this discourse without implementing their racial triggers. People of colour are the global majority but colonial borders still dissect us down into “ethnic minorities.”

Whilst this book is about North America, we need to stop thinking about racism as something only “bad people” do, as DiAngelo says in her book. Racism isn’t only the tool of the far right. It’s also the tool of seemingly good institutions; from policing to higher education and The Academy. We need to be looking at the Enoch Powells of this world, and not just the little man.

Robin DiAngelo’s words will pick at the skin of White people’s fragility and their lack of racial stamina to have these conversations. The White people that manage to get through this book to the end will undergo some humility (I hope), analysing all the times they’ve been treated better than their non-White colleagues in exact same situations. She is intentionally provoking discomfort to be critical of the sensitivity White people show when you tell them they are part of society’s institutional racism. And that well-meaning White folks aren’t as liberal and democratic as they often think they are.

In light of Brexit and the ongoing Windrush Crisis #Jamaica50, I am not sure we can say racism in this country is nuanced (anymore). The Tory government’s obsession with stop and search as a way to combat County Lines and knife crime… you cannot arrest your way out of this, nor can you continue to stop Black people at a disproportionate rate to White people, and expect a community with shaky faith in the police to support you.

Rich White people are the biggest smokers of marijuana I know; I can say that because I went to private school, but on what planet has whiteness ever been linked to criminality?

“This book is centred in the white western colonial context, and in that context white people hold institutional power.” In this quote, we need to understand that racism is more than individuals calling each other names, it’s a system of power. In the UK, it privileges whiteness, economically and socially. All people have racial bias, but only with White people in Europe and North America is that bias backed by institutional power.

It is not the job of people of colour to explain racism to White people. When a White woman cries (they’re also complicit in white supremacy), Black men get hurt. Racism is the problem of White people. They created it and the responsibility to dismantle those systems lies with the White masses.

People that look like me are there to support, but racism is trauma. Is it really ethical to expect people of colour to take on this burden? What White people need to ask themselves, and in the words of the late James Baldwin, “why it was necessary to have a nigger in the first place because I’m not a nigger, I’m a man, but if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need it.”

And perhaps in the reading and knowledge-gathering at FBL’s Book Club, in how whiteness operates (insidious and pervasive), united we can attempt to push back against the racial inequalities at work in the University on a day-to-day.

In Meghan, we must study the Black History of the British elite

Since Meghan Markle and Harry stepped back, the British media have talked about whether their treatment of Meghan Markle has been racist. A discussion has which has certainly produced its own irony and racism. The Royal Family is a historically White institution; however, in light of this, I think it needs to be acknowledged that Meghan Markle is not the first non-White member, but is part of a longer, subtler history of Black / biracial aristocracy in Britain.

When Meghan joined, it was lorded progress. Yet, is diversity progress if non-normative figures are being sent into already hostile environments? Is Britain a racist country? “Definitely, 100%” said Stormzy. Meghan coming from a country that is overtly racist in the tint of Jim Crow Laws, ICE and ALEC, to a country that’s more subtle… this brand of racism from the UK media was almost colonial, simply without the violence. From comments on her “exotic DNA” to descriptions of her being “(almost) straight outta Compton”, as well as comparing her newborn son to a chimpanzee.

But Meghan wasn’t the first Black or biracial person to gain a pass into the British elite. German princess (Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz), who then became Queen of England on marrying King George III in 1761. Historian Mario de Valdes y Cocom thinks she was of the direct line from a Black Portuguese royal family, Alfonso III and his mistress, Ourana, a Moor.

In the BBC docuseries Black and British and the book of the same name, historian David Olusoga talks about a slave turned bare-knuckle boxer by the name of Bill Richmond. In Richmond Unchained, historian and Richmond’s biographer Luke Williams discusses Richmond’s pioneering achievements in boxing, winning 17 of 19 professional fights but also being a member of English aristocracy, an invitee to the Coronation of George IV.

What’s more, however, Bill was a member of eighteenth-century Britain and went on “to take Georgian Britain” by storm, says Olusoga. Originally from Staten Island, he came to this country as a young man, possibly a teenager. Born into slavery and somehow finding himself on the bloody battlefields in America’s War for Independence. Surviving the war, he made his way to Britain as a servant for Hugh Percy, Duke of Northumberland.

Whilst we had Bill Richmond in the thick of Georgian Britain, in the halls of Kenwood House lived a girl by the name of Dido Elizabeth Belle. Born to a slave, and Rear Admiral Sir John Lindsay, she lived the life of an heiress in London. Essentially, “too Black” for the social scene of Georgian Britain but “too elite” to live with the servants. Living in the late 1700s, she would have been witness to some of the landmark slave trade cases, including “The Zong” which was ruled on by her uncle, Lord Chief Justice Mansfield.

The slave ship Zong left Africa with 470 slaves. Slaves were not seen as people. They were material objects to be touched, poked and prodded at any White person’s choosing. Often raped by the slave masters, as shown with Patsy (Lupita Nyong’o) in 12 Years a Slave and Hilde (Kerry Washington) in Django Unchained, they were property, not people.

As with the Zong, many captains took more than ships could handle to ensure maximum profits. The Zong was overloaded. Many got sick and died from disease and malnutrition. Captain Collingwood is reported to have jettisoned some of the cargo in order to save the ship and provide the ship owners with insurance money. In total one hundred and thirty-three slaves were thrown overboard (chained together) for the seamen to try to claim back on the insurance, since slaves weren’t people, but property.

Though the film Belle is depicted as fiction, the Zong Case is not. The massacre and the court trial happened. Dido was real. Her love interest John Davinier was real. Lord Mansfield was real. Kenwood House still stands in London. The Zong was one of the many benchmark cases of the Slave Trade. Director Amma Asante puts these atrocities into a format that everyone can understand, not just people that understand legal jargon.

Not only were there Black Georgians in Britain, there were Black Victorians as well. But we’ll have more in that later.

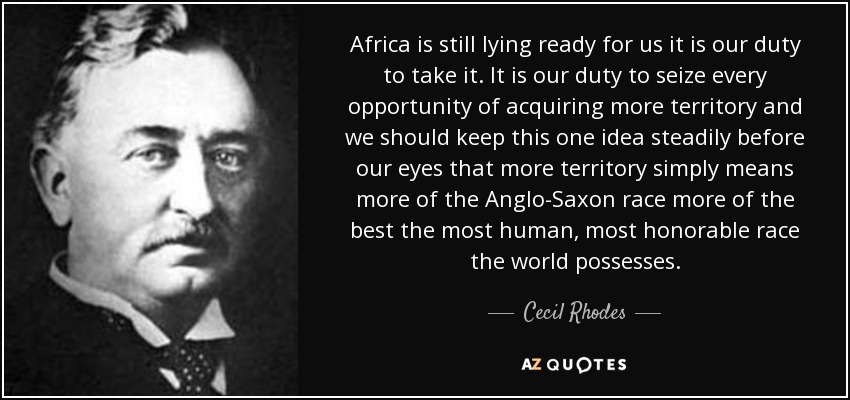

One of history’s most “important” businessmen (in my opinion) is not a household name but should be, His name was Cecil Rhodes: businessman, colonialist, and White Supremacist – believing in the superiority of Whites over everyone else. And he is in-part at least responsible for the apartheid regime in southern Africa, building its foundations in the 19th century.

Cecil Rhodes wanted to build a railway line from Cape Town in South Africa through Botswana and up to Cairo, Egypt

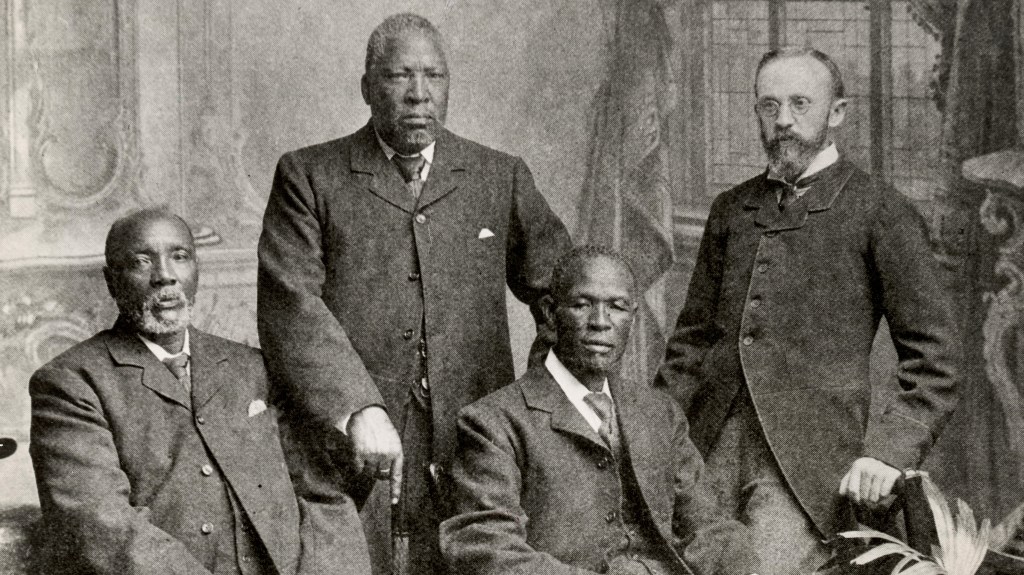

In the late 19th century, the Bechuanaland Protectorate (modern-day Botswana) was under threat of being forced to join what was then British South Africa Company under Cecil Rhodes. The “merger”, so to speak, would mean that the country would have no control of its own governance and would have to do everything Rhodes and the South Africa Company said.

Looking at the threat this would bring to the their people, in 1895 the three chiefs (Kharma, Sebele and Batheon) went to the heart of Empire, to parlay with Queen Victoria. This soulless landgrabbing happened throughout Africa and Rhodes was instrumental in what became ‘The Scramble for Africa’, where European powers divided Africa among them. Exploiting it for its resources, the locals suffered in the next stage of colonisation.

King Kharma and the other chiefs knew that Cecil Rhodes’ railway was a pretext for colonisation. This was a protectorate – claimed by Britain by ruled by local leaders.

Constantly being fobbed off by the colonial secretary, they decided it was time to meet the British people. Running a propaganda campaign to rally people to their cause, they then got their meeting playing Rhodes, the colonial secretary and Queen Victoria off against each other with tact.

Unlike the other nations, this country’s deal was kind of unique. Most colonised countries entered into colonialism at the end of a gun. Under some sort of threat. These Black men came to the heart of Empire showing British aristocracy that these colonial racist stereotypes of Africa and Africans were falsehoods. They came to England, defeating Rhodes at his own game, contradicting his own views of Africa and Africans.

What this story says to me is:

1) It contradicts the racial thinking of the time – Black people to be stupid and savage. Shows us to be intelligent and with values.

2) That these kings had come to the heart of Empire, outwitting the seemingly “superior race”, Rhodes’ had been outmaneuvered.

3) They saw there were differing opinions in Britain, they knew that the British Empire was bureaucratic.

Queen Victoria’s goddaughter / protegé was a called Sarah Forbes Bonetta. A number of events involving a one Captain Forbes, his ship the Bonetta and King Gezo of the Dahomey saw Sarah (Aina) pass into the care of Queen Victoria. First living with Forbes and his wife, Sarah then lived with Victoria and Albert at Windsor Castle before marrying a Sierra Leonean called James Davies, having a daughter, who they named Victoria after the Queen.

It’s strange to think she would have walked many of the streets Black Britons walk today, just 150 years ago. That brief word on Sarah is a snapshot but she lived a remarkable life, returning to Africa to raise a family.

Watching the ITV adaptation of Thackeray’s Vanity Fair and then starting the book of the same name, we are introduced to a Bajan heiress called Rhoda Schwartz. Despite it being fiction, this inspiration for Thackeray to write this character must have come from somewhere. How many Dido Belles have been lost to history? And what of the Black African Tudors that inhabited the courts of both Henry VII and Henry VIII? What of the Black and brown people in Tudor England, irrespective of wealth, class or rank?

From John Blanke “[…] depicted with dark skin and wearing a turban […]” (Kaufmann, 2017, p7) – to Katherine of Aragon’s lady of the bed chamber who Olusoga says was “a North African Moor called Catalina” – to Prince Jaquoah, “christened John, after John Davies” (Kaufmann, 2017, p176) – to the African Roman general Septimus Severus, Britain’s Black History goes back centuries, including those today we’d say inhabit White spaces.

Despite this history being a lot of blanks and hypotheses, it’s sad that their words are almost lost to us looking back. No biographies. Simply moments in time. Nonetheless, the tide is turning against the naysayers.

And British history is not just White. It can’t only be White. We have always been multiracial and Meghan wasn’t the first, nor will she be the last, as the future is mixed-race.

Works of Note

Bidisha (2017). Tudor, English and black – and not a slave in sight. Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/29/tudor-english-black-not-slave-in-sight-miranda-kaufmann-history [Accessed 28 January 2020].

Brown, DeNeen L. (2018). Meghan Markle, Queen Charlotte and the wedding of Britain’s first mixed-race royal. Washington Post [online]. Available from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/05/15/meghan-markle-queen-charlotte-and-the-wedding-of-britains-first-mixed-race-royal/ [Accessed 22 January 2020].

Clarke, S. (2019). British Presenter Fired After Posting Chimp Picture With Royal Baby Tweet. Variety [online]. Available from: https://variety.com/2019/tv/news/royal-baby-chimp-tweet-bbc-danny-baker-fired-prince-harry-meghan-markle-1203209699/ [Accessed 31st January 2020].

de Valdes y Cocom, M. (N/A). The Blurred Racial Lines of Famous Families. PBS Frontline [online]. Available from: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/secret/famous/royalfamily.html [Accessed 28 January 2020].

Goodfellow, M. (2020). Yes, the UK media’s coverage of Meghan Markle really is racist. Vox [online]. Available from: https://www.vox.com/platform/amp/first-person/2020/1/17/21070351/meghan-markle-prince-harry-leaving-royal-family-uk-racism [Accessed 27 January 2020].

Jeffries, S. (2009). Was this Britain’s first black queen? Guardian [online]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/mar/12/race-monarchy [Accessed from January 28 2020].

Johnson, R (2016). RACHEL JOHNSON: Sorry Harry, but your beautiful bolter has failed my Mum Test. Daily Mail [online]. Available from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-3909362/RACHEL-JOHNSON-Sorry-Harry-beautiful-bolter-failed-Mum-Test.html [Accessed January 26 2020].

Kaufmann, Miranda. (2017). Black Tudors: The Untold Story. London: Oneworld.

Myers Dean, W. (1999). At Her Majesty’s Request: An African Princess in Victorian England. New York: Scholastic Inc.

Olusoga, D. (2017). Black and British: A Forgotten History. London: Pan Macmillan.

Sawyer, P. (2017). Poignant note from Queen Charlotte to dead son’s nanny throws light on the sadness of George III. The Telegraph [online]. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/01/28/poignant-note-queen-charlotte-dead-sons-nanny-throws-light-sadness/ [Accessed January 20 2020].

Stezano, M (2017/18). The 19th-Century Black Sports Superstar You’ve Never Heard Of. History [online]. Available from: https://www.history.com/news/the-18th-century-black-sports-superstar-youve-never-heard-of [Accessed January 28 2020].

Styles, R. (2020). EXCLUSIVE: Harry’s girl is (almost) straight outta Compton: Gang-scarred home of her mother revealed – so will he be dropping by for tea? Daily Mail [online]. Available from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3896180/Prince-Harry-s-girlfriend-actress-Meghan-Markles.html [Accessed January 24 2020].

Thackeray Makepeace, W. (1848). Vanity Fair. London: Macmillan.

Van der Kiste, J. (2018). Queen Victoria’s African Princess. Devon: A&F

Walk-Morris, T (2017). Five Things to Know About Queen Charlotte. Smithsonian [online]. Available from: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smartnews-arts-culture/5-things-you-didnt-know-about-queen-charlotte-180967373/ [Accessed 28 January 2020].

Williams, L. (2015). Richmond Unchained. London: Amberley Publishing.

Small island, smaller minds: it takes a village

“In times of crisis, the wise build bridges while the foolish build barriers. We must find a way to look after one another, as if we were one single tribe.” – King T’Challa, Black Panther

If you are White British, racism is not a narrative you would be familiar with, as far as your daily existence is concerned. Whilst racism has always been a day in the life for people of colour, there was a spike in hate crime in 2016 with the Brexit vote. Brexit was triggered on January 31 in the same way it began, in the tint of racism and violence. And that does not always mean physical pain on another. Violence can be verbal abuse, whether that’s direct from the horse’s mouth in terms like “Paki” and “nigger” , or on a note in a Norwich tower block.

On January 31, or Brexit Day, CBBC posted a video from its Horrible Histories TV show on Twitter. British comedian Nish Kumar preludes the clip with an introduction. What was meant to be a child-friendly look at British things, flag-waving Brexiteers turned into something else entirely. They don’t take to being told that tea, cotton and sugar aren’t British things, but products of a very British means of production called colonisation.

In 2018, we began to feel the quakes of the Windrush crisis, which is still happening today. When members of the Windrush Generation were / are being deported under then prime minister Theresa May’s hostile environment policy, Amber Rudd simply fell on her sword. Despite this scandal being buried by “other news”, this hysteria simply echoes that of when they first arrived, well-depicted in Pathé film reels.

In Andrea Levy’s Small Island, this is Britain at its bones. Britain as I know it. Little Britain. This text is about deception; and the biggest ruse is that Britain is a tolerant place and all are welcome. This was just after the Second World War. However, the stories of the working class is at its core, irrespective of skin colour. It has often been said that Britain is the least racist society in Europe, but this is only really if you happen to be born into the calm of being affluent, White and British. And the people publicising these opinions are from this same demographic, those born into privilege.

Brexit won’t only make us poorer economically, it’ll make us poorer spiritually. Smaller. Brittler. Littler. Alone. Isolated. No longer a nation others looked to, like in the postwar years – now little Britain drunk in jingoism and nationalism. As Nigel Farage waves his miniature union jacks in Brussels, I see bodybags. “Get Brexit Done” was the phrase; yes, Brexit is done and Britain with it. I feel tremors in Scotland and calls for independence will echo, as the Act of the Union (1707) will be undone.

In the years to come, will we still be Britain? Or will we go back to being England? Little old England in the vice of America. Pals with real British problems like institutional racism, austerity and auctioning off people’s health to American businessmen. A hopelessness, sledgehammered like Jeremy’s Labour by billionaire-owned media. 14m people currently live in poverty and it will only get worse, a Red Scare and Depression at dawn.

In this winter of discontent, we will see how art runs tandem with activism. The next ten years will do wonders for arts. Some of the greatest art came at times of hardship and oppression, from the Slave Trade to the Vietnam War. Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator will be a solace of sorts for me. His final speech at the end of that film is a call to humanity to find their humanity. “One does not have to be a Jew to be anti-Nazi” says Chaplin in his biography. One does not have to be Black to be anti-racism, or a woman to be a feminist or pro-choice, or gay or trans to be pro-LGBT rights.

Forty-seven years of membership put to bed because a portion of the country wanted to be independent. Independent from whom? A country with a history of colonisation and paternalism, who celebrate with the Commonwealth Games and say The Empire is no more. Whilst the Third Reich harked back to the Golden Age of the Roman Empire, Britain harks back to its nostalgia for Slavery and Suez, colonialism raised at half-mast.

Whilst many think The Empire to be a good thing, I picture images of my ancestors hanging from trees in the Caribbean. I think about pilgrims and preachers pontificating the word of God whilst raping Black women slaves throwing them down a hole. I think about how stop and search began way back in colonial times, and: Partition, Boer Concentration Camps, Opium Wars, Easter Risings, and the genocide of the indigenous American peoples.

In the mid-twentieth century, author James Baldwin spent time in Paris, fleeing the violent Jim Crow America. When the Brexit vote went through, I was in Hyderabad, India. Another former-British colony. Say Churchill in India and you’d lose a hand. That’s hyperbole, but he is not loved there. And in India, I felt more welcome than when I came home, told to go home the day after the vote. My cultural bond for Britain thawed, my patience with it.

Whiteness walks into a bar and waves his flag. If you are not rich, you are closer to the poverty line than owning a Lambo. If you could not afford rent if you lost your job, you have no business voting Conservative or cheering come our exit from the EU. Race, gender, sexuality, disability… what unites us all is class but these characteristics make those issues ten times worse.

To say I am nervous about Brexit would be an understatement. To the working class and people of colour that voted against the futures of their children and grandchildren by voting leave, and Tory, (in the last election), I am speechless. Whilst racism has always been part of the British way of life, I never used to look over my shoulder walking down Northampton streets.

But Hell is here and devils walks amongst us; a long winter has come, and we are a long way from dawn.

“BAFTA stands for ‘Black actors fuck off to America'” – Gina Yashere

Performing Arts has been part of my life for as long as I can remember, and arts in general is something I’m passionate about, more specifically: literature, theatre and film / television. However, the recent awards scandal with BAFTA is really just one more example of how institutional violence is something Britain refuses to come to terms with. Whether we’re talking the education sector, or policing (Macpherson 1999), criminal justice (Lammy 2017), or in government (Windrush Crisis), or Britain’s film and television industry.

There’s twelve and half years between me and my brother. Yet, ever since he was born he has shown an aptitude for the arts and great promise in both stage and screen, having done work with Screen Northants and Royal & Derngate, as well as with the Royal Shakespeare Company (The RSC).

He really is very good, but how the UK treats Black actors is atrocious. I know from discussions that he wants to be a serious actor and I wonder if he will have to fight the same racism and implicit bias that David Oyelowo and Idris Elba did. When will Black British actors stop having to prove themselves abroad before they are taken seriously in their own country?

“BAFTA stands for ‘Black actors fuck off to America'” joked comedian Gina Yashere in docuseries Black is the New Black

It’s funny because it’s true. And Britain’s close-minded attitudes towards race and diversity does not help the cause. Over the years, Black British actors, and even Black and brown Brits from other non-UK backgrounds have gone to America in hoards and made it. Whilst America is not famous for its racial harmony, it is at least thirty years ahead when it comes to race. And when it comes to diversity within acting and the performing arts industry, they are better off. If Ashton decided he wanted to jump ship and move to Los Angeles, or NYC (for theatre), I would help him pack!

We are losing talent because of Britain’s inability to change: Nathalie Emmanuel, Freeman Agyeman, Dev Patel, John Boyega, Riz Ahmed, Henry Golding, Gemma Chan, Daniel Kaluuya and Gugu Mbatha-Raw are just a handful of our great actors that followed the likes of Idris Elba, David Oyelowo, and Naomi Harris to the United States, a country that we criticise for its racism. But what of racism at home? Is Britain racist? “Definitely, 100%” said Stormzy. And I would argue his misquote was also true.

Idris Elba made it as Stringer Bell in The Wire before the BBC picked him up for Luther and David Oyelowo has been in a number of high profile Hollywood films, including Last King of Scotland and Selma. Don’t misunderstand me, America is not perfect but at least it doesn’t put a blue plaster on a tumour and call it progress. Our diversity, the thing we boast about is leaving, meanwhile BAFTA celebrated its seventh consecutive year of no women in the Best Directors race, let alone nods to women of colour.

Black Americans make 13% of the US population (est. 48.4m), but Black Britons only make up 3% of the UK population (est. 1.9m), so I guess this shows why there’s more visibility for Black actors in the United States.

However, I’m by no means saying America is a utopia, I just believe America is better put-together where diversity is concerned. Hamilton, one of the biggest musicals ever is a global phenomenon made up of almost entirely Black and brown actors, as will be the new adaptation of In the Heights directed by American director Jon. M Chu (Crazy Rich Asians), with songs written by Lin Manuel-Miranda, the mastermind behind Hamilton.

And America’s many sub-genres; from Spike Lee creating the Blaxploitation genre from the mid-80s to the world of Tyler Perry with Madea, and “Black” comedies like Girls’ Trip and Little, Black cinema is massive in the States. Whilst I don’t believe you can allot race to film and call it a genre, I do believe you can make films about Black lives and celebrate it. Whilst there is Black cinema in the UK, it’s a drop in the ocean and not mainstream.

My father named me for Tre from the classic 1991 film Boyz n the Hood, out of this film the world was shown a plethora of Black characters, including the mild-mannered Tre, but also his father played by an early career Laurence Fishburne. Black-led Rom-Coms like Girls’ Trip, most recently but even historically, such as Love and Basketball or even something more serious like Juice, or Poetic Justice, with musician-actor Janet Jackson.

If my brother at seventeen or eighteen years old decided to try his luck in Los Angeles or New York, I wouldn’t blame him. Black British actors are making waves in America. Black Britain has faced criticism from the likes of Samuel. L Jackson, where he suggested Jordan Peele’s Get Out would have been better with a Black American lead. Yet, what both countries share is Black actors fighting for roles whilst their White colleagues (i.e Cumberbatch, Streep, Blunt, Fassbender) don’t have to, nor are their White colleagues under the same criticism from their peers and the establishment.

In the essay collection, The Good Immigrant, in his essay ‘Airports and Auditions’, actor-poet Riz Ahmed states “the reality of Britain is vibrant multiculturalism, but the myth we export is an all-white world of lords and ladies.” The period drama genre for example has been under scrutiny for being too white. The Britain we sell overseas is Jane Austen novels, The Crown and Middlemarch. It’s the stuff in canon literature, not Hollyoaks or our close to two thousand-year history of Black people in the British Isles.

The Britain we sell overseas is not the Britain my brother is growing up in. My generation, the Harry Potter Generation; we grew up with Hogwarts Tamagochis and Beyblade. I grew up with Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh. And even in Harry Potter, in this diverse Britain we celebrate, the lack of Black characters or characters who weren’t White is blinding. And even the Dean Thomases and Cho Changs of that world have few lines between them.

And Ashton is growing up with more knowledge (and pride) around being a Black Briton, in the tint of great influences, incl. Stormzy, Afua Hirsch, Santan Dave, David Olusoga, and Reni Eddo-Lodge, all of whom speak truth to the power.

I don’t want him to feel low, but you must wonder if it was designed against people like him from the start? If #DecoloniseHE in the education sector is anything to go by, the answer is yes. Will he find roles for him, or will he be one of those Black British actors that effs off to America? Will he have to do what Noel Clarke (Kidulthood) did and write, direct and produce his own films because Britain’s film industry does not cater for its diverse talent?

And that is a sad state of affairs indeed. Tyler Perry being the first Black American to own a film production studio is a testament to what is possible in America. It’s not uncommon to see a Black professor in an American university. There are only 85 Black British professors in UK universities. It’s not rare to see Black lawyers or Black teachers in the US but there’s an over-representation of White British teachers in UK secondary schools and in HE.

As a writer in Northamptonshire, a county wrapped in classism, you also have to think about race’s impact on class. To enjoy theatre, but only on occasion seeing people and stories that reflect Britain’s diversity. Whilst my vocation is not reliant on looks, the struggle for Black actors is really a struggle. It was never meant to be easy. To live in a Britain that pushes images of us that can only succeed in entertainment and sports, but seem nonexistent when it comes to discussing Black intellect and political ideas.

And it’s really a solemn thought that this happy boy might one day be forced to go to America because in British style, like all our structures, it caters for the few, not the many.

Works of Note

Adegoke, Y and Uviebinené, E. (2019). Slay in Your Lane. London: 4th Estate

Advance HE (2018). ‘Equality in higher education: statistical report 2018,’ ecu.ac.uk, [online]. Available from: https://www.ecu.ac.uk/publications/equality-higher-education-statistical-report-2018/ [Last accessed 30 December 2019]

Ahmed, S. (2018). Rocking the Boat: Women of Colour as Diversity Workers. In: Arday, J., Mirza, S. (eds). Dismantling Race in Higher Education: Racism, Whiteness and Decolonising the Academy. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 331 –348

Home Office. (1999). The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry. (Chairperson: William Macpherson). London: TSO

Ministry of Justice (2017). The Lammy Review. (Chairperson: David Lammy MP). London: TSO