Home » Articles posted by Sallek Yaks Musa

Author Archives: Sallek Yaks Musa

Leading with Integrity: Standing Firm Against the Echo Chamber

Sallek Yaks Musa

Truth hurts. Few appreciate it, and even fewer defend it when it threatens comfort or convention. My understanding of this reality came through personal experience, an early lesson in leadership that continues to shape how I view authority and the dangerous allure of sycophancy.

Two decades ago, my journey into education began in an unusual way. For five years, my father had spoken passionately about his dream to establish a nursery, primary, and secondary school that would help transform the state of education in our city. In 2004, we finally decided to bring that dream to life. What followed was both the beginning of my passion for education and my first encounter with the complexity of leading people and institutions.

The process of establishing the school was neither smooth nor simple. I remember every detail – the struggle to develop infrastructure that met required standards and equip it, the endless paperwork, the defence of proposals before career bureaucrats, and the scrutiny of regulatory inspections. Each stage tested our patience and resolve, yet the experience became invaluable. It offered me lessons no textbook could teach and laid the solid foundation of my leadership philosophy.

By the time we received approval to open in September 2005, I led over a hundred interviews to staff the school. That period sharpened my ability to read people and situations intuitively, a skill I have trusted ever since. The school went on to succeed beyond expectation: self-sustaining, thriving, and impacting tens of thousands of young lives. Yet, behind this success lay one central principle – truth.

My commitment to truth shaped the school’s ethos. Every decision, from recruitment to remuneration, from board meetings to relationships with parents and staff, was guided by sincerity. My academic training would later frame this conviction in philosophical terms. With leadership, I align with Auguste Comte’s positivist epistemology, rooted in the belief that truth is objective, concrete, and independent of social interpretation. This, I discovered, is easier preached than practised.

In practice, truth is disruptive. It offends vanity, challenges comfort, and exposes deception. My insistence on it often placed me in direct opposition to others on the Board, including my father. He later confided that while my defiance was difficult to bear, it forced him to confront realities he had overlooked. I further learned that the defender of truth often stands alone. My father eventually recognised what I had resisted all along: the quiet but corrosive power of flattery.

Sycophancy, though rarely discussed openly, remains one of the greatest dangers to leadership. It thrives where authority is unquestioned, and dissent discouraged. Flattery seduces leaders into believing they are infallible. It builds an echo chamber that filters information, reinforcing biases and creating an illusion of competence. Over time, this isolation from reality becomes costly as decisions are made on false premises, honest critics are sidelined, and mediocrity is rewarded over merit. But this is not a modern affliction.

The 16th-century political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli, in The Prince, warned rulers of this very danger. He cautioned that the wise Prince must deliberately surround himself with people courageous enough to speak the truth, for flatterers ‘take away the liberty of judgment.’ Centuries later, the philosopher Hannah Arendt would echo this concern, arguing that the loss of truth in public life leads to moral decay and political collapse. The persistence of these warnings shows how deeply entrenched sycophancy remains in systems of power.

The psychology behind flattery is deceptively simple. It feeds the ego, providing comfort that masquerades as respect and support. Leaders, craving affirmation, often mistake it for loyalty. But as Daniel Kahneman and other cognitive theorists have shown, human judgment is easily distorted by bias and praise. Flattery, therefore, becomes not merely a social nicety but a psychological trap, one that blinds decision-makers to inconvenient truths.

For those newly stepping into student’s course representative roles, these lessons carry special relevance. Academic leadership is often less about authority and more about stewardship, the quiet work of creating conditions where ideas can flourish, student’s voices are heard, and students can contribute honestly. Resist the temptation to surround yourself with agreeable voices. Encourage critique, invite dissent, and create a culture where questioning is not perceived as confrontation but as commitment to excellence. The strength of representation lies not in the leader’s popularity but in their willingness to confront complexity, admit limits, and make decisions grounded in truth rather than convenience.

As the once “baby school” turned twenty this year, its anniversary passed in my absence. My father’s message of appreciation reached me nonetheless, and his words reminded me why truth, though often costly, remains indispensable to authentic leadership. He wrote:

Remember, son, true leadership lies in listening attentively, sieving facts from noise, embracing unpopular voices, acting on truth, and valuing others above yourself.

That reflection closed a circle that began two decades ago. It reminded me that leadership rooted in truth is not about being right but about being realistic. It is about creating space where honesty thrives, even when it unsettles.

Flattery may offer short-term peace, but truth builds long-term strength and relationships. The leader who welcomes honesty, however uncomfortable, not only guards against failure but also nurtures a culture of integrity that outlives their term.

Twenty years after that first bold step into education, leading teams and managing academic programmes in education, I remain convinced that truth is not a luxury in leadership – it is its lifeline. Legacies are not defined by applause or position, but by the integrity to lead with sincerity, listen without fear, and act with unwavering commitment to what is right. People are ultimately remembered not for simply opposing flattery, but for the truth they championed and the courage they demonstrated to stand firm in their convictions when it mattered most.

Uncertainties…

Sallek Yaks Musa

Who could have imagined that, after finishing in the top three, James Cleverly – a frontrunner with considerable support – would be eliminated from the Conservative Party’s leadership race? Or that a global pandemic would emerge, profoundly impacting the course of human history? Indeed, one constant in our ever-changing world is the element of uncertainty.

Image credit: Getty images

The COVID-19 pandemic, which emerged in late 2019, serves as a stark reminder of our world’s interconnectedness and the fragility of its systems. When the virus first appeared, few could have foreseen its devastating global impact. In a matter of months, it had spread across continents, paralyzing economies, overwhelming healthcare systems, and transforming daily life for billions. The following 18 months were marked by unprecedented global disruption. Lockdowns, travel restrictions, and social distancing became the new norms, forcing us to rethink how we live, work, and interact.

The economic fallout was equally staggering. Supply chains crumbled, unemployment surged, and entire industries teetered on the brink of collapse. Education was upended as schools and universities hastily shifted online, exposing the limitations of existing digital infrastructure. Yet, amid the chaos, communities displayed remarkable resilience and adaptability, demonstrating the need for flexibility in the face of uncertainty.

Beyond health crises, the ongoing climate and environmental emergencies continue to fuel global instability. Floods, droughts, erratic weather patterns, and hurricanes such as Helene and Milton not only disrupt daily life but also serve as reminders that, despite advances in meteorology, no amount of preparedness can fully shield us from the overwhelming forces of nature.

For millions, however, uncertainty isn’t just a concept; it’s a constant reality. The freedom to choose, the right to live peacefully, and the ability to build a future are luxuries for those living under the perpetual threat of violence and conflict. Whether in the Middle East, Ukraine, or regions of Africa, where state and non-state actors perpetuate violence, people are forced to live day by day, confronted with life-threatening uncertainties.

On a more optimistic note, some argue that uncertainty fosters innovation, creativity, and opportunity. However, for those facing existential crises, innovation is a distant luxury. While uncertainty may present opportunities for some, for others, it can be a path to destruction. Life often leaves little room for choice, but when faced with uncertainty, we must make decisions – some minor, others, life-altering. Nonetheless, I am encouraged that while we may not control the future, we must navigate it as best we can, and lead our lives with the thought and awareness that, no one knows tomorrow.

Embracing Technology in Education: Prof. Ejikeme’s Enduring Influence

Sallek Yaks Musa, PhD, FHEA

When I heard about the sudden demise of one of my professors, I was once again reminded of the briefness and vanity of life —a topic the professor would often highlight during his lectures. Last Saturday, Prof. Gray Goziem Ejikeme was laid to rest amidst tributes, sadness, and gratitude for his life and impact. He was not only an academic and scholar but also a father and leader whose work profoundly influenced many.

I have read numerous tributes to Prof. Ejikeme, each recognizing his passion, dedication, and relentless pursuit of excellence, exemplified by his progression in academia. From lecturer to numerous administrative roles, including Head of Department, Faculty Dean, Deputy Vice Chancellor, and Acting Vice Chancellor, his career was marked by significant achievements. This blog is a personal reflection on Prof. Ejikeme’s life and my encounters with him, first as his student and later as an academic colleague when I joined the University of Jos as a lecturer.

Across social media, in our graduating class group, and on other platforms, I have seen many tributes recognizing Prof. Ejikeme as a professional lecturer who motivated and encouraged students. During my undergraduate studies, in a context where students had limited voice compared to the ‘West,’ I once received a ‘D’ grade in a social psychology module led by Prof. Dissatisfied, I mustered the courage to meet him and discuss my case. The complaint was treated fairly, and the error rectified, reflecting his willingness to support students even when it wasn’t the norm. Although the grade didn’t change to what I initially hoped for, it improved significantly, teaching me the importance of listening to and supporting learners.

Prof. Ejikeme’s classes were always engaging and encouraging. His feedback and responses to students were exemplary, a sentiment echoed in numerous tributes from his students. One tribute by Salamat Abu stood out to me: “Rest well, Sir. My supervisor extraordinaire. His comment on my first draft of chapter one boosts my morale whenever I feel inadequate.”

My interaction with Prof. Ejikeme significantly shaped my teaching philosophy to be student-centered and supportive. Reflecting on his demise, I reaffirmed my commitment to being the kind of lecturer and supervisor who is approachable and supportive, both within and beyond the classroom and university environment.

Prof. Ejikeme made teaching enjoyable and was never shy about embracing technology in learning. At a time when smartphones were becoming more prevalent, he encouraged students to invest in laptops and the internet for educational purposes. Unlike other lecturers who found laptop use during lectures distracting, he actively promoted it, believing in its potential to enhance learning. His forward-thinking approach greatly benefited me and many others.

Building on Prof. Ejikeme’s vision, today’s educators can leverage advancements in technology, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), to further enhance educational experiences. AI can personalize learning by adapting to each student’s pace and style, providing tailored feedback and resources. It can also automate administrative tasks, allowing educators to focus more on teaching and student interaction. For instance, AI-driven tools can analyse student performance data to identify learning gaps, recommend personalized learning paths, and predict future performance, helping educators intervene proactively.

Moreover, AI can support academics in research by automating data analysis, generating insights from large datasets, and even assisting in literature reviews by quickly identifying relevant papers. By embracing AI, academics can not only improve their teaching practices but also enhance their research capabilities, ultimately contributing to a more efficient and effective educational environment.

Prof. Ejikeme’s willingness to embrace new technologies was ahead of his time, and it set a precedent for leveraging innovative tools to support and improve learning outcomes. His legacy continues as we incorporate AI and other advanced technologies into education, following his example of using technology to create a more engaging and supportive learning experience.

Over the past six months, I have dedicated significant time to reflecting on my teaching practices, positionality, and the influence of my role as an academic on learners. Prof. Ejikeme introduced me to several behavioural theories in social psychology, including role theory. I find role theory particularly crucial in developing into a supportive academic. To succeed, one must balance and ensure compatible role performance. For me, the golden rule is to ensure that our personal skills, privileges, dispositions, experiences from previous roles, motivations, and external factors do not undermine or negatively impact our role or overshadow our decisions.

So long, Professor GG Ejikeme. Your legacy lives on in the countless lives you touched.

Disclaimer: AI may have been used in this blog.

Teaching, Learning, and Some Grey Areas: A Personal Reflection

Sallek Yaks Musa

Trigger warning: sections of this blog may contain text edited/generated by machine learning AI.

Growing up in a farming community, I gained extensive knowledge of agricultural practices and actively participated in farming processes. However, this expertise did not translate into my performance in Agricultural Science during senior high school. Despite excelling in other subjects and consistently ranking among the top 3 students in my class, I struggled with Agricultural Science exams, much to the surprise of my parents.

I remembered my difficulties with Agricultural Science while reflecting on the UK Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF) for teaching and supporting learning in higher education. This reflection occurred shortly after a student asked me about the minimum qualifications needed to become a lecturer in higher education (HE). Unlike in lower educational levels, a specific teaching certification is not typically required in HE. However, most lecturing positions require a postgraduate certification or higher as a standard. Additionally, professional memberships are crucial and widely recognized as necessary to ensure lecturers are endorsed, guided, and certified by reputable professional bodies.

Reputable professional organizations typically establish entry criteria, often through summative tests or exams, to assess the suitability and competency of potential members. In the UK, Advanced HE stands as one of the widely acknowledged professional bodies.

Advanced HE offers four levels of professional recognition: associate, fellow, senior, and principal fellows. Applicants must evidence proficiency and comprehension across three pivotal competency areas: areas of activity, core knowledge, and professional values, as outlined in the UKPSF Dimensions of the Framework. Among others, these competency areas emphasize the importance of prioritising the enhancement of the quality of education, evaluating assessment strategies, and recognizing and supporting diverse learners throughout their educational journey.

It was not until the third term of my first year in senior high school that I began to understand why I struggled with Agricultural Science. Conversations with classmates who consistently excelled in the subject shed light on our collective challenge, which I realized extended beyond just myself to include our teacher. With this teacher, there was little room for innovation, self-expression, or independent thinking. Instead, success seemed contingent upon memorization of the teacher’s exact notes/words and regurgitating them verbatim. Unfortunately, cramming and memorization were skills I lacked, no matter how hard I tried. Hence, I could not meet the teachers’ marking standard.

The truth of this became glaringly apparent when our teacher went on honeymoon leave after marrying the love of his life just weeks before our exams. The junior class Agricultural Science teacher took over, and for the first time, I found success in the subject, achieving a strong merit. Unsurprising, even the school principal acknowledged this achievement this time around when I was called for my handshake in recognition of my top 3 performance.

In our school, the last day of each term was always eventful. An assembly brought together students and teachers to bid farewell to the term, recognize the top performers in each class with a handshake with the principal, and perhaps offer encouragement to those who struggled academically. This tradition took on a more solemn tone on the final day of the school year when the names of students unable to progress to the next class were announced to the entire assembly. This is a memory I hope I can revisit another day, with deeper reflection.

My pursuit of Advanced HE professional membership stirred memories of my struggles with Agricultural Science as a student, highlighting how our approach to teaching and assessment can profoundly impact learners. In my own experience, failure in Agricultural Science was not due to a lack of understanding but rather an inability to reproduce the teacher’s preferred wording, which was considered the sole measure of knowledge. Since then, I have been committed to self-evaluating my teaching and assessment practices, a journey that began when I started teaching in primary and secondary levels back in September 2005, and eventually progressed to HE.

A recent blog by Dr. Paul Famosaya, questioning whose standards we adhere to, served as a timely reminder of the importance of continuous reflection beyond just teaching and assessment. It further reinforced my commitment to adopting evidence-based standards, constantly refining them to be more inclusive, and customizing them to cater to the unique needs of my learners and their learning conditions.

The Advanced HE UKPSF offers educators a valuable resource for self-assessing their own teaching and assessment methods. Personally, I have found the fellowship assessment tasks at the University of Northampton particularly beneficial, as they provide a structured framework for reflection and self-assessment. I appreciate how they spur us as educators to acknowledge the impact of our actions on others when evaluating our teaching and assessment practices. Certainly, identifying areas for improvement while considering the diverse needs of learners is crucial. In my own self-evaluation process, I often find the following strategies helpful:

- Aligning teaching and assessment with learning objectives: Here, I evaluate whether my teaching methods and assessment tasks align with the module’s intended learning outcomes. For example, when teaching Accounting in senior secondary school, I assess if the difficulty level of the assessment tasks matches or exceeds the examples I have covered in class. This approach has informed my teaching and assessment strategies across various modules, including research, statistics, data analysis, and currently research at my primary institution, as well as during my tenure as a visiting lecturer at another institution.

- Relatability and approachability: An educator’s approachability and relatability play a significant role in students’ willingness to seek clarification on assessment tasks, request feedback on their work, and discuss their performance. This also extends to their engagement in class. When students feel comfortable approaching their educator with questions or concerns, they are more likely to perceive assessments as fair and supportive. Reflecting on how well you connect with students is essential, as it can enhance learning experiences, making them more engaging and meaningful. Students are more inclined to actively participate in class discussions, seek feedback, and engage with course materials when they view the educator as accessible and empathetic. If students leave a class, a one-on-one meeting, or a feedback session feeling worse off due to inappropriate word choices or communication style, word may spread, leading to fewer attendees in future sessions. Therefore, fostering an environment of approachability and understanding is crucial for promoting a positive and supportive learning atmosphere.

- Enhancing student engagement: Prior to joining the UK HE system, I had not focused much on student engagement. In my previous teaching experiences elsewhere, learners were consistently active, and sessions were lively. However, upon encountering a different reality in the UK HE environment, I have become proactive in seeking out strategies, platforms, and illustrations that resonate with students. This proactive approach aims to enhance engagement and facilitate the learning process.

- Technological integration: Incorporating technology into teaching and assessment greatly enhances the learning process. While various technologies present their unique challenges, the potential benefits and skills acquired from utilizing these tools are invaluable for employability. However, there is a concern regarding learners’ overreliance on technological aids such as AI, referencing managers, discussion boards, and other online tools, which may lead to the erosion of certain cognitive skills. It is essential to question whether technological skills are imperative for the modern workplace. Therefore, one must evaluate whether technology improves the learning experience, streamlines assessment processes, and fosters opportunities for innovation. If it does in the same way that the changing nature of work favours these new skills, then educators and universities must not shy away from preparing and equipping learners with this new reality lest learners are graduated unprepared due to an attempt to be the vanguard of the past.

- Clarity of instruction and organisation: Evaluate whether students comprehend expectations and the clarity of instructions. Drawing from my experience in the not-for-profit sector, I have learned the effectiveness of setting objectives that are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound). Emphasizing SMART learning outcomes is crucial in teaching and learning. However, where learning outcomes are broad, ambiguous, or subject to individual interpretation, educators must ensure that assessment marking criteria are clearly articulated and made clear to learners. This clarification should be provided in assessment briefs, support sessions, and during class contacts. Reflecting on this ensures that students understand what is expected of them and prevents educators from inadvertently setting them up for failure. It becomes apparent that assessment criteria lacking validity and reliability hinder the accurate measurement of student understanding and skills, even if same has been consistently used over time. Therefore, continuous reflection and refinement are essential to improve the effectiveness of assessment practices. Afterall, reflection should be a mindset, and not just a technique, or curriculum element.

- Feedback mechanisms: The effectiveness of feedback provided to students is always important. Reflecting on whether feedback is constructive and actionable could help to foster learning and improvement, irrespective of how short or lengthy the feedback comments are. Anyone who has passed through the rigour of research doctoral supervision would appreciate the role of feedback in all forms on learner progression or decision to drop out.

- Inclusivity and diversity: In a diverse educational setting, it is imperative to engage in continuous reflection to ensure that teaching and assessment practices are inclusive and responsive to the varied backgrounds, learning peculiarities, and abilities of learners. Educators hold a significant position that can either facilitate or hinder the progress of certain learners. In cases where barriers are inadvertently created, unconscious bias and discrimination may arise. Therefore, ongoing reflection and proactive measures are essential to mitigate these risks and create an environment where all students can thrive.

- Ethical considerations: Teaching and assessment practices carry ethical responsibilities. Fundamentally, educators must prioritize fairness, transparency, and integrity in all assessment procedures, setting aside personal biases and sentiments towards any individual, cohort, or group of students. It is equally important to consider how one’s position and instructional choices influence students’ well-being and academic growth. Striving for ethical conduct in teaching and assessment ensures a supportive and equitable learning environment for all students.

End.

I’m not Black; my Friends and I are Brown, not Black

I recently began the process of preparing my child for the imminent transition to a new school situated in a diverse community. Despite being born into a similarly diverse environment, his early educational exposure occurred in an ethnically varied setting. Venturing into this new chapter within a racially diverse community has sparked a keen interest in him.

My child soon articulated a perspective that challenged conventional racial labels. He asserted that he and his friend Lucien are not accurately described as ‘black,’ rather he believes they are ‘brown.’ He went further to contest the classification of a lady on TV, who was singing the song “Ocean” by Hillsong, as ‘white.’ According to him, his skin is not black like the trousers he was wearing, and the lady is not white like the paper on my lap. This succinct but profound statement held more critical significance than numerous conversations I’ve encountered in my over five years of post-PhD lecturing.

The task at hand, guiding an under seven-year-old questioning the conventional colour-based categorisation, proved challenging. How do I convince an under seven-year-old that his knowledge of colours should be limited to abstract things and that persons with brown toned skin are ‘black’ while those with fair or light toned skinned are ‘white’? I found myself unprepared to initiate this complex conversation, but his persistent curiosity and incessant ‘why prompts’ compelled me to seek creative ways to address the matter. Even as I attempted to distract myself with a routine evening shower and dinner, my mind continued to grapple with the implications of our conversation.

Post-dinner, my attempt to engage in my usual political news catch-up led me to a YouTube vlog by Adeola titled ‘How I Almost Died!’ where she shared her pregnancy challenges. One statement she made struck a chord: ‘if you are a black woman and you are having a baby in America, please always advocate for yourself, don’t ever keep quiet, whatever you are feeling, keep saying it until they do something about it’ (18:39). This sentiment echoed similar experiences of tennis star Serena Williams, who faced negligence during childbirth in 2017.

The experiences of these popular ‘black’ women not only reminds me that the concept ‘black’ and ‘white’ are not only symbolic, but a tool for domination and oppression, and disadvantaging the one against the other. Drawing inspiration from Jay-Z’s ‘the story of O.J’, the song drew attention to the experiences of race, success, and the complexities of navigating the world as a ‘black’ individual. In the song, two themes stood out for me, the collective vulnerability to prejudice and the apparent bias in the criminal justice system towards ‘black’ people. In the UK, both proportional underrepresentation in staff number and proportional overrepresentation of minoritized groups in the criminal justice system and the consequences therefrom is still topical.

Jay-Z’s nuanced understanding of ‘black’ identity rejects simplistic narratives while emphasising its multifaceted nature. The verse, “O.J. ‘like I’m not black, I’m O.J.’ Okay” underscores the challenges even successful ‘black’ individuals face within racial systems. As criminologists, we recognize the reflection of these issues in daily experiences, prompting continuous self-reflexivity regarding our values, power positions, and how our scholarly practice addresses or perpetuates these concerns. Ultimately, the question persists: Can a post-racially biassed world or systems truly exist?

Journeys Through Time: From British Empire’s Transportation Punishment to Contemporary Immigration Challenges

On November 29, 2023, our level 5 criminology students embarked on a visit to the National Museum of Justice in Nottingham. The trip had multiple objectives, including providing students with an out-of-classroom understanding of archives, immersing them in the crime and justice model in Britain from the 1840s to the 1940s, exposing them to rich historical records, deepening their understanding of archival research materials, and offering them first-hand experience on the treatment and conditions of suspected and convicted individuals in the past.

The museum, a vital historical site, not only facilitates reflection on the history of crime and justice in Britain but also offers an opportunity to ponder the trends and trajectory of changes since 1614.

Among the myriad opportunities for learning and research, transportation stood out for me. This form of punishment, prevalent in the British Empire from the 17th to the mid-19th centuries, forcibly removed convicted individuals from Britain to penal colonies, primarily in North America and later in Australia. This severe punishment involved separating convicts from their families and homeland, subjecting them to harsh and unfamiliar environments. Notably, individuals as young as nine were sent to America in 1614, with sentences ranging from 7 to 14 years or life. In addition to its punitive aspect, transportation provided forced cheap labour for the British government in exploited colonies, contributing to the expansion of the British Empire.

The deplorable conditions during transportation, its impact on the history of Australia and other colonies, and its role in the development of a unique convict society underscore its harsh and brutal nature. Despite its significant role, transportation was gradually abolished in the mid-19th century due to growing unpopularity and expense.

The historical context of transportation as a punitive measure serves as a backdrop for understanding current immigration and eviction plans in the UK, particularly concerning refugees and asylum seekers arriving in small boats. Though transportation was phased out in the mid-19th century, the echoes of forcibly moving individuals can be juxtaposed with contemporary immigration policies.

The British Empire’s transportation punishment, involving forced removal to distant penal colonies, parallels the challenges faced by today’s refugees and asylum seekers. While historical transportation was driven by criminality, current immigration plans involve vulnerable populations seeking refuge and safety, raising uncertainties about the safety they can find in Rwanda.

Examining the deplorable conditions of transportation provides a lens to scrutinize the humanitarian aspects of current immigration policies, emphasizing the toll on human life, challenges during migration, and impacts on indigenous populations.

Both transportation and the Rwanda plan share a common objective of removing unwanted individuals from British society, albeit for different reasons. Transportation aimed to punish criminals, while the Rwanda plan intends to deter dangerous journeys across the English Channel.

However, both policies face criticism from human rights groups, asserting their cruelty and violation of international law. Despite this, steps to implement the Rwanda plan are underway, indicating a willingness to sacrifice the well-being of vulnerable individuals for political expediency. The parallels between transportation and the Rwanda plan serve as a stark reminder of the dark side of British history, with asylum seekers and refugees sent to Rwanda facing the prospect of indefinite detention and potential persecution upon return to their countries of origin.

While transportation was abolished in the mid-19th century, exploring its historical significance encourages reflection on the complexities of modern immigration and eviction plans. This analysis highlights how punitive measures, whether historical or contemporary, shape societies, impact individuals, and contribute to a nation’s broader narrative.

Saluting Our Sisters: A Reflection on the Living Ghost of the Past

Sarah Baartman. Image source: https://shorturl.at/avLO4

In the 20th century, many groups of people who had been overpowered, subdued, and suppressed by imperialist expansionist movements under arbitrary boundaries began challenging their subjugation. These emancipation struggles resulted in the emergence of quasi-independent, self-governed African nation-states. However, avaricious socio-economic opportunists were aided into political leadership and have continued to perpetuate imperial interests while crippling their own emerging nations. Decades later, it has become clear that these ‘new states’ have become shackled under the grips of strong and powerful men who lead a backward and dysfunctional system with the majority of people impoverished while they enervate justice and political institutions.

Prior to this, the numerous nation states now recognised as African states had developed their distinct social, political, and economic systems which emerged from and reflected their distinctive norms and cultural values. Barring communal disputes and conflicts, robust inter-communal associations, interaction, and commerce subsisted amongst the nations, and paced socio-economic developments were occurring until external incursions under different guises began. Notably, the tripartite monsters of transatlantic slave trade, pillage of natural resources, and colonisation which not only lasted for centuries, disrupted the steady pace and development of these nations. It destroyed all existing social fabric and capital of the people, and forcefully installed a religious, socio-political, and economic systems that are alien to the people.

Ironically, while the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism were perpetuated under the guise of a “civilizing mission,” it took over three centuries for the “civilised” to realise that these abhorrent incursions were far from being civilising, and that they themselves required the civilisation they purported to be administering. However, while one might imagine that this awareness would lead to remorse and guilt-tripped sincere repentance for the pillage, pain, and atrocities, the abolition and relinquishing of political power to natives, the following events symbolized the contrary. Neo-colonialism was born, and international systems and conglomerates have continued the pillage on different fronts as aided by the greedy political class. Thus, it is unsurprising that yet again, strong, and powerful men are revolting against and deposing the self-perpetuating, avaricious socio-economic opportunists who wield political power against the interests of their nations in series of military coup d’état.

It is clear that the legacy of exploitation and subjugation has brought about a new set of challenges. Leaders entrusted with the responsibility of fostering prosperity in their nations often succumbed to personal gain, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation reminiscent of the imperialist era. This grim reality creates a stark contrast: while the majority of citizens are trapped in poverty, a powerful minority wields disproportionate influence, eroding the foundations of justice, economic prosperity, and political stability. As a result, for the vulnerable, seeking safety, economic freedom, and escaping from dysfunctional systems through deadly and illegal migration to other parts of the world becomes the only viable option. However, unbeknownst to many, the lands they risk everything to reach are grappling with their own challenges, including issues of acceptance and association with once labelled ‘uncivilized’ peoples.

Black History Month sheds light on these challenges faced by the black community and other marginalized ethnic groups globally. This year, the theme ‘Saluting our Sisters’ invites us to reflect on the contributions of Black women to society and the challenges they continue to face. It is also important to reflect deeply on how we consciously or unconsciously perpetuate rather than disprove, discourage, and distance ourselves from sustaining and growing the living ghost of the past. As Chimamanda urges, perhaps considering a feminist perspective in our actions, practices, and behaviour can be a powerful step toward recognizing and acknowledging how we perpetuate these problems. Dear Sister, I admire and salute you for your resilience and tenacity in making the world a better place.

Unravelling the Niger Coup: Shifting Dynamics, Colonial Legacies, and Geopolitical Implications

On July 26, the National Council for Safeguarding the Homeland (CNSP) staged a bloodless coup d’état in Niger, ousting the civilian elected government. This is the sixth successful military intervention in Africa since August 2020, and the fifth in the Sahel region. Of the six core Sahelian countries, only Mauritania has a civilian government. In 2019, it marked its first successful civilian transition of power since the 2008 military intervention, which saw the junta transitioning to power in 2009 as the civilian president.

Military intervention in politics is not a new phenomenon in Africa. Over 90% of African countries have experienced military interventions in politics with over 200 successful and failed coups since 1960 – 1, (the year of independence). To date, the motivation of these interventions revolves around insecurity, wasteful and poor management of state resources, corruption, and poor and weak social governance. Sadly, the current situation in many African countries shows these indicators are in no short supply, hence the adoption of coup proofing measures to overcome supposed coup traps.

The literature evidences adopting ethnic coup proofing dynamics and colonial military practices and decolonisation as possible coup-proofing measures. However, the recent waves of coups in the Sahel defer this logic, and are tilting towards severing ties with the living-past neocolonial presence and domination. The Nigerien coup orchestrated by the CNSP has sent shockwaves throughout the region and internationally over this reason. Before the coup, Mali and France had a diplomatic row. The Malian junta demanded that France and its Western allies withdraw their troops from Mali immediately. These troops were part of Operation Barkhane and Taskforce Takuba. A wave of anti-French sentiments and protests resulted over the eroding credibility of France and accusation of been an occupying force. Mohamed Bazoum, the deposed Nigerien president, accepted the withdrawn French troops and its Western allies in Niger. This was frowned at by the Nigerien military, and as evidenced by the bloodless coup, similar anti-French sentiments resulted in Bazoum’s deposition.

The ousting of President Bazoum resulted in numerous reactions, including a decision by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), of which Niger is a member and is currently chaired by Nigerian President Bola Ahmed Tinubu. ECOWAS demanded the release and reinstatement of President Bazoum, imposed economic sanctions, and threatened military intervention with a one-week ultimatum. Some argued that the military intervention is unlikely, and some member states pledged support to the junta. At the end of the ultimatum, ECOWAS activated the deployment of its regional standby force but it remains unclear when it will intervene and what the rules of engagement will be. Nonetheless, the junta considers any such act as an aggression, and in addition to closing its airspace, it is understood to have sought support from Wagner, the Russian mercenary.

Amongst the citizenry, while some oppose the military intervention, there is popular support for both the intervention and the military with thousands rallying support for the junta. On 6 August, about 30,000 supporters filled the Niamey stadium chanting and applauding the military junta as they parade the crowd-filled stadium. Anti-French sentiments including a protest that led to an attack on the French embassy in Niger followed the declaration of the coup action. In the civil-military relations literature, when a military assumes high political roles yet has high support from society over such actions, it is considered as a popular praetorian military (Sarigil, 2011, p.268). While this is not a professional military attribute (Musa and Heinecken, 2022), it is nonetheless supported by the citizenry.

In my doctoral thesis, I argued that in situations where the population is discontent and dissatisfied with the policies of the political leadership, a civil-military relations crisis could result. I argued that “as citizens are aware that the military is neither predatory nor self-serving, they are happy trusting and supporting the military to restore political stability in the state. It is possible that in situations where political instability becomes intense, large sections of the citizenry could encourage the military to intervene in politics” (Musa, 2018, p.71). The recent waves of military intervention in Africa, together with anti-colonial sentiments evidences this, and further supports my argument on the role of the citizenry in civil-military relations. For many Nigeriens including Maïkol Zodi who leads an anti-foreign troops movement in Niger, the coup symbolises the political independence and stability that Francophone Africa has long desired.

Thus, as the events continue to unfold, I would like to end this blog with some questions that I have been thinking about as I try to make sense of this rather complex military intervention. The intervention is affecting international relations and has the potential to destabilise the current power balance between the major powers. It could also lead to a military conflict in Africa, which would be a disaster for the continent.

- How have recent coups in the Sahel region signalled a shift away from colonial legacies, and how are these sentiments reshaping political dynamics?

- What is the significance of the diplomatic tensions between Mali and France, and how might they have influenced the ousting of President Bazoum and the reactions to it?

- Given the surge in military interventions in politics across the Sahel region, how does this trend reflect evolving dynamics within the affected countries, and does this has the potential to spur similar interventions in other African States?

- What lessons can be drawn from Mauritania’s successful transition from military to civilian rule in 2019, and how might these insights contribute to diplomatic discussions around possible transition to civilian rule in Niger?

- Are the decisions of ECOWAS influenced by external pressures, how effective is ECOWAS’s approach to addressing coups within member states, and how does the Niger coup test the regional organization’s capacity for conflict resolution?

- To what extent do insecurity, mismanagement of resources, corruption, and poor governance collectively contribute to the susceptibility of African nations to military interventions?

- How can African governments strike a balance between improving the quality of life and coup-proofing measures, and which is most effective for preventing or mitigating the risk of military interventions?

- What are the potential ramifications of the coup on the geopolitical landscape, especially in terms of altering power dynamics among major players?

- What are the implications of the coup for regional stability, and how might it contribute to the potential outbreak of conflict and could it destabilize ongoing counterterrorism efforts and impact cooperation among countries in addressing common security threats?

- Why do widespread demonstrations of support for the junta underscore the sentiments of political independence and stability that resonate across Francophone Africa?

- Given the complexities of the situation, what measures can be taken to ensure long-term stability, governance improvement, and democratic progress in Niger?

- Ultimately, is the western midwifed democracy in Africa serving its purpose, and given the poor living conditions of the vast populace in African countries as measured against all indices, can these democracies serve Africans?

Navigating these questions is essential for comprehending the implications of the coup and the potential outcomes for Niger and its neighbours. In an era where regional stability and international relations are at stake, a nuanced understanding of these multifaceted issues is imperative for shaping informed responses and sustainable solutions.

References

Musa, S.Y. (2018) Military Internal Security Operations in Plateau State, North Central Nigeria: Ameliorating or Exacerbating Insecurity? PhD, Stellenbosch University. Available from: https://scholar.sun.ac.za/handle/10019.1/104931. [Accessed 7 March 2019].

Musa, S.Y., Heinecken, L. (2022) The Effect of Military (Un)Professionalism on Civil-Military Relations and Security in Nigeria. African Security Review. 31(2), 157–173.

Sarigil, Z. (2011) Civil-Military Relations Beyond Dichotomy: With Special Reference to Turkey. Turkish Studies. 12(2), 265–278.

Is Criminology Up to Speed with AI Yet?

On Tuesday, 20th June 2023, the Black Criminology Network (BCN) together with some Criminology colleagues were awarded the Culture, Heritage, and Environment Changemaker of the Year Award 2023. The University of Northampton Changemaker Awards is an event showcasing, recognising, and celebrating some of the key success and achievements of staff, students, graduates, and community initiatives.

For this award, the BCN, and the team held webinars with a diverse audience from across the UK and beyond to mark the Black History Month. The webinars focused on issues around the ‘criminalisation of young Black males, the adultification of Black girls, and the role of the British Empire in the marking of Queen Elizabeth’s Jubilee.’. BCN was commended for ‘creating a rare and much needed learning community that allows people to engage in conversations, share perspectives, and contextualise experiences.’ I congratulate the team!

The award of the BCN and Criminology colleagues reflects the effort and endeavour of Criminologists to better society. Although Criminology is considered a young discipline, the field and the criminal justice system has always demonstrated the capacity to make sense of criminogenic issues in society and theorise about the future of crime and its administration/management. Radical changes in crime administration and control have not only altered the pattern of some crime, but criminality and human behaviour under different situations and conditions. Little strides such as the installation and use of fingerprints, DNA banks, and CCTV cameras has significantly transformed the discussion about crime and crime control and administration.

Criminologist have never been shy of reviewing, critiquing, recommending changes, and adapting to the ever changing and dynamic nature of crime and society. One of such changes has been the now widely available artificial intelligence (AI) tools. In my last blog, I highlighted the morality of using AI by both academics and students in the education sector. This is no longer a topic of debate, as both academics and students now use AI in more ways than not, be it in reading, writing, and formatting, referencing, research, or data analysis. Advance use of various types of AI has been ongoing, and academics are only waking up to the reality of language models such as Bing AI, Chat GPT, Google Bard. For me, the debate should now be on tailoring artificial intelligence into the curriculum, examining current uses, and advancing knowledge and understanding of usage trends.

For CriminologistS, teaching, research, and scholarship on the current advances and application of AI in criminal justice administration should be prioritised. Key introductory criminological texts including some in press are yet to dedicate a chapter or more to emerging technologies, particularly, AI led policing and justice administration. Nonetheless, the use of AI powered tools, particularly algorithms to aid decision making by the police, parole, and in the courts is rather soaring, even if biased and not fool-proof. Research also seeks to achieve real-world application for AI supported ‘facial analysis for real-time profiling’ and usage such as for interviews at Airport entry points as an advanced polygraph. In 2022, AI led advances in the University of Chicago predicted with 90% accuracy, the occurrence of crime in eight cities in the US. Interestingly, the scholars involved noted a systemic bias in crime enforcement, an issue quite common in the UK.

The use of AI and algorithms in criminal justice is a complex and controversial issue. There are many potential benefits to using AI, such as the ability to better predict crime, identify potential offenders, and make more informed decisions about sentencing. However, there are also concerns about the potential for AI to be biased or unfair, and to perpetuate systemic racism in the criminal justice system. It is important to carefully consider the ethical implications of using AI in criminal justice. Any AI-powered system must be transparent and accountable, and it must be designed to avoid bias. It is also important to ensure that AI is used in a way that does not disproportionately harm marginalized communities. The use of AI in criminal justice is still in its early stages, but it has the potential to revolutionize the way we think about crime and justice. With careful planning and implementation, AI can be used to make the criminal justice system fairer and more effective.

AI has the potential to revolutionize the field of criminology, and criminologists need to be at the forefront of this revolution. Criminologists need to be prepared to use AI to better understand crime, to develop new crime prevention strategies, and to make more informed decisions about criminal justice. Efforts should be made to examine the current uses of AI in the field, address biases and limitations, and advance knowledge and understanding of usage trends. By integrating AI into the curriculum and fostering a critical understanding of its implications, Criminologists can better equip themselves and future generations with the necessary tools to navigate the complex landscape of crime and justice. This, in turn, will enable them to contribute to the development of ethical and effective AI-powered solutions for crime control and administration.

The Moral Dilemma of Using Artificial Intelligence

Background

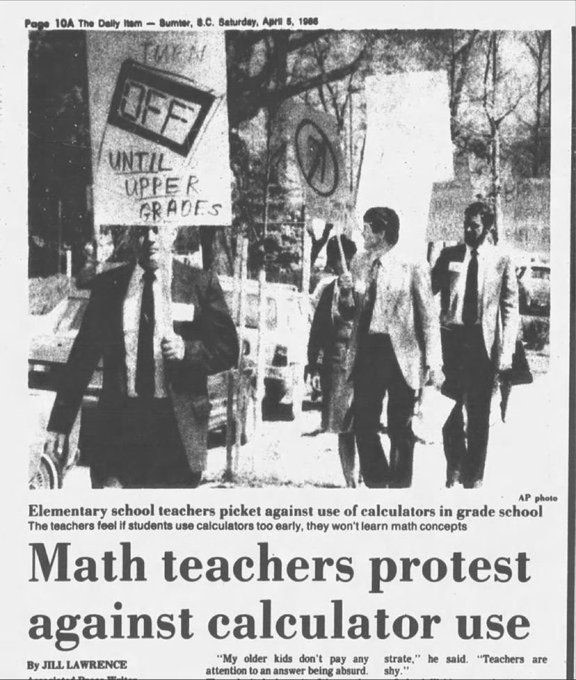

Many academics, students, and industry practitioners alike are currently faced with the moral dilemma of whether to use or apply artificial intelligence (AI) to different aspects of their work and assessments. However, this is not the first-time humans are faced with such a moral dilemma, particularly in academia. Between 2003 and 2005 when I wrote at least 3 entrance examinations administered by the Joint Admission Matriculation Board Examination for university admission seekers in Nigeria, the use of electronic or scientific calculators were prohibited. Few years afterwards, the same exam board that prohibited my generation from using calculators for our accounting and mathematics exams started providing the same scientific calculators to students registered for the same exam. Understandably, AI is significantly different from scientific calculators, but similar rhetoric and condemnation resulted from the introduction of calculators in schools, same as the emergence of Google with its search capabilities.

For the most part, ChatGPT, the free OpenAi model publicly released in November 2022 drew public attention to the use and capability of AI and is often considered as the breakthrough of AI. However, prior to this, humans have long embraced and used certain aspects of AI to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, problem-solving, and decision-making. Many academics not only use reference managers, but also encourage students to do so. We also use and teach students how to use the numerous computer-aided data analysis software for statistical and qualitative data analysis given the potential and capability of these software to replicate tasks that would ordinarily take us longer to accomplish. These are but few examples of some of the AI tools we use, while many others exist.

Types and examples of AI

There are several types of AI, including machine learning, natural language processing, expert systems, robotics, and computer vision. Machine learning is the commonly used type of AI. It involves training algorithms to learn from data and improve their performance over time, typical examples include Google Bard which performs similar tasks as ChatGPT. Natural language processing allows machines to understand and interpret human language, while expert systems are designed to replicate the decision-making capabilities of human experts. Robotics involves the development of machines that can perform physical tasks, and computer vision focuses on enabling machines to interpret and analyse visual information. Other common examples of AI include virtual personal assistants like Siri and Alexa, self-driving cars, and facial recognition software. With the wide array of AI tools, it is obvious that AI can be applied in different fields of human endeavour.

Application of AI

AI is currently being used in various institutions of society, including healthcare, finance, education, transportation, and the military. In healthcare, AI is being used to develop personalized treatment plans, predict disease outbreaks, improve medical image analysis, and carebots consultations is a near possibility. In finance, AI is being used for fraud detection, risk management, and algorithmic trading. In transportation, self-driving cars and drones are being developed and currently tested using AI, while in the military, AI is being used for autonomous weapons systems and intelligence gathering. In education, AI is being used for personalized learning, student assessment, referencing, and teacher training through the help of numerous AI tools. I recently responded to reviewer feedback on a book chapter and in doing so, I noticed my reference list which was not spotted by my reviewers was not appropriately aligned with the examples provided from the publisher. It would take me 2 hours to format the list despite already having the complete information of sources I cited. Interestingly, I did not spend half of this time on the reference list of my doctoral thesis because I used a reference manager.

Benefits of AI

Clearly, AI has many potential benefits. It has the potential to improve efficiency and accuracy in various industries, leading to cost savings and improved outcomes. AI can also provide personalized experiences for users, such as in the case of virtual assistants and personalized learning platforms. More so, where properly applied, it would not only improve productivity and save time, but result in increased efficiency. Researchers would appreciate the ability to make sense of bulky data using clicks and programmed controls in graphical, visual, or even coded formats. In healthcare, AI can improve diagnosis and treatment, leading to better patient outcomes. In addition, AI can be used for environmental monitoring and conservation efforts. The benefits from the use and application of AI across human endeavours are legion and I would be understating the significance if I attempt to elaborate further.

Shortcomings of AI, Concerns, and Reactions

Nonetheless, AI evokes certain concerns. New York City education department reportedly blocked ChatGPT on school devices and networks, and in respond to a tweet on this, Elon Musk replied, ‘it’s a new world. Goodbye homework.’ Musk’s reply reflects the array of reactions and responses emanating from the understanding of society with the capability of AI tools. And without a doubt, machine learning AI tools such as ChatGPT and Google Bard can be used to generate essay contents, likewise content for academic work. I imagine students have already began taking advantage of the capabilities of these tools, including others capable of summarising articles. Some Tweeps who regularly tweet about the capability and how to use AI tools have experienced astronomical growth in the number of their followers and engagement with such tweets over the past few months.

Without a doubt, academics have reasons to be concerned, particularly because AI undermines learning and scholarship by offering easy alternatives to reading, learning, and engaging with course materials. Students could generate essays with AI and gain unfair advantage over non-users and although the machine learning models do generate false, bias, and discriminatory results, they could over time generate the capability to overcome these. Claims have also been made that automation using AI has the potential to result in job losses for academics and other professionals, but beyond this, concerns over data safety and regulation are rife.

AI Regulation

Some tech leaders including Elon Musk recently signed a statement urging that further development of AI beyond the capability of ChatGPT 4 should be halted until adequate regulations are put in place as it portends profound risks to society. The Turnitin plagiarism software provider which acclaims itself as ‘the leading provider of academic integrity solutions’ introduced and integrated the Turnitin’s AI writing detection tool for their service users. Universities and other users may likely adopt this to discourage students from using AI for assessments. However, the practicability of this enforcement is still challenging as issues around real-world false-positive report rates have been observed. An alternative approach adopted by some publishers including Taylor & Francis, Sage, and Elsevier is that authors declare the use of AI in their work with justification. Italy recently blocked ChatGPT over privacy concerns prompting the significance of AI regulation.

Conclusion

AI has the potential to improve efficiency and accuracy in various industries, leading to cost savings and improved outcomes, however, it is important to be aware of the potential risks associated with the technology. While AI has significant benefits, such as improved efficiency and accuracy, it also has drawbacks that must be considered. Academics must find ways to balance the benefits and drawbacks of AI to ensure that learning and scholarship are not undermined. It is important to recognize that AI is not a substitute for reading, learning, and engaging with course materials, and it should be used as a tool to augment human intelligence rather than replace it. Equally, it is also important to ensure that AI is used in a responsible and ethical manner. By carefully considering the pros and cons of AI, we can ensure that it is used to its full potential while minimizing the risks.

PS. Some parts of this blog were edited/generated by AI.