Home » Articles posted by liammiles1

Author Archives: liammiles1

Will Keir Starmer’s plans to abolish NHS England, help to save the NHS?

In a land-mark event, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer has unveiled plans to abolish NHS England, to bring the NHS back into government control. Starmer justifies much of this change with streamlining operations and enhancing efficiency within the NHS, that in recent years has faced a backlash following long queues and an over-stretched staff pool. Moreover, this is part of Starmer’s plan to limit the power of control from bureaucratic systems.

NHS England was established in 2013 and has taken control and responsibility of the NHS’s daily operational priorities. Primarily, NHS England is invested in allocating regional funds to local health care systems and ensuring the smooth delivery of health care across the NHS. However, concerns, particularly in Parliament have been raised in relation to the merging of NHS England and the Department’s of Health and Social care that is alleged by critics to have brought inefficient services and an increase of administrative costs.

Considering this background, the plans to abolish NHS England, for Starmer come under two core priorities. The first is enhancing democratic accountability. This is to ensure that the expenditures of the NHS are contained within government control, thus it is alleged that this will improve efficiency and suitable allocation of spending. The second is to reduce the number of redundancies. This is backed by the idea that by streamlining essential services will allow for more money to be allocated to fund new Doctors and Nurses, who of course work on the front line.

This plan by Starmer has been met with mixed reviews. As some may say that it is necessary to bring the NHS under government control, to eliminate the risks of inefficient services. However, some may also question if taking the NHS under government control may necessarily result in stability and harmony. What must remain true to the core of this change is the high-quality delivery of health care to patients of the NHS. The answer to the effectiveness of this policy will ostensibly be made visible in due course. As readers in criminology, this policy change should be of interest to all of us… This policy will shape much of our public access to healthcare, thus contributing to ideas on health inequalities. From a social harm perspective, this policy is of interest, as we witness how modes of power and control play a huge role in instrumentally shaping people’s lives.

I am interested to hear any views on this proposal- feel free to email me and we can discuss more!

Britain’s new relationship with America…Some thoughts

Within the coming weeks, Keir Starmer is due to meet Donald Trump and in doing so has offered an interesting view into the complexities of managing diplomacy in the modern age. Whilst the UK and US work collaboratively through bi-lateral trade agreements, and national security collaborations, the change in power structures within the UK and USA marks significant ideological difference that can arguably present a myriad of implications for both countries and for those countries who are implicated by these relations between Britain and America. In this blog, I will outline some of the factors that ought to be considered as we fast-approach this new age of international relations.

It can be understood that Starmer meeting Trump, despite some ideological difference is rooted in a pragmatic diplomacy approach and for what some might say is for the greater good. In an age of continual risk and uncertainty, allyship across nations has seldom been more necessary nor consolidated. On addressing issues including climate change, national security, trade agreements within a post-Brexit adversity, the relationship between America and Britain I sense is being foregrounded by Starmer’s Labour Government.

Moreover, I consider that Starmer should tread carefully and not appear globally as though he is too strongly aligned with Trump’s policies, especially on foreign policy. This mistake was once made by Tony Blair, following the New Beginnings movement after 9/11. It is essential that whilst we maintain good relations with America, this does not come at a cost to our own sovereignty and influence on global issues. I see here an opportunity for Starmer to re-build Britain’s place on the global stage. Despite this as what some strategists might call a ‘bigger picture’, it goes without saying that Starmer may face backlash from his peers based on his willingness to enter a liaison with Trump’s Government. For many inside and outside of the Labour Party, the politics of Trump are considered dangerous, regressive, and ideologically dumbfounded. I happen to agree with much of these sentiments, and I think there is a risk for Starmer… that will later develop into a dilemma. This dilemma will be between appeasing the party majority and those who hold traditional Labour values in place of moving further into the clutches of the far right, emboldened by neoliberalism. It is no secret however that the Labour party has entered a dangerous liaison with neoliberalism and has alienated many traditional Labour voters and has offered no real political alternative.

Considering this, I sense an apprehension is in the air regarding Starmer’s relationship building with America and Donald Trump, that some might argue might be more counter-productive than good. Starmer must demonstrate political pragmatism and arguably the impact of this government and the governments to come will weigh on these relations… Albeit time will tell in determining how these future relations are mapped out.

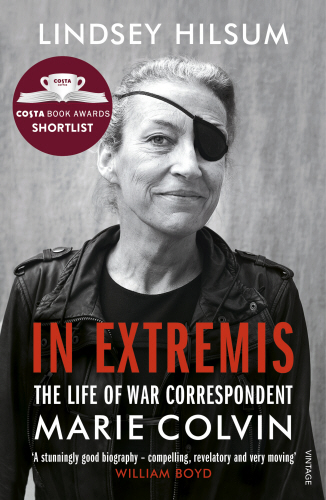

A review of In-Extremis: The Life of War Correspondent Marie Colvin

Recently, I picked up a book on the biography of Marie Colvin, a war correspondent who was assassinated in Syria, 2012. Usually, I refrain from reading biographies, as I consider many to be superficial accounts of people’s experiences that are typically removed from wider social issues serving no purpose besides enabling what Zizek would call a fetishist disavowal. It is the biographies of sports players and singers, found on the top shelves of Waterstones and Asda that spring to mind. In-Extremis, however, was different. I consider this book to be a very poignant and captivating biography of war correspondent Marie Colvin, authored by fellow journalist Lindsey Hilsum. The book narrates Marie’s life before her assassination. Her early years, career ventures, intimate relationships, friendships, and relationships with drugs and alcohol were all discussed. So too were the accounts of Marie’s fearless reporting from some of the world’s most dangerous conflict zones, including Sri-Lanka, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria. Hilsum wrote on the events both before Marie’s exhilarating career and during the peak of her war correspondence to illustrate the complexities in her life. This reflected on Marie’s insatiability of desire to tell the truth and capture the voices of those who are absent from the ‘script’. So too, reporting on the emotions behind war and conflict in addition to the consistent acts of personal sacrifice made in the name of Justice for the disenfranchised and the voiceless.

Across the first few chapters, Hilsum wrote on the personal life of Marie- particularly her traits of bravery, resilience, persistence, and an undying quest for the truth. Hilsum further delved into the complexities of Marie’s personality and life philosophies. A regular smoker, drinker and partygoer with a captivating personality that drew people in were core to who Marie was according to Hilsum. However, the psychological toils of war reporting became clear, particularly as later in the book, the effects of Marie’s PTSD and trauma began to present itself, particularly after Marie lost eyesight in her left eye after being shot in Sri-Lanka. The eye-patch worn by Marie to me symbolised the way she carried the burdens of her profession and personal vulnerabilities, particularly between maintaining her family life and navigating her occupational hazards.

In writing this biography, Hilsum not only mapped the life of one genuinely awesome and inspiring woman, but also highlighted the importance of reporting and capturing the voices of the casualties of war. Much of her work, I felt resonated with my own. As an academic researcher, it is my job to research on real-life issues and to seek the truth. I resonated with Marie’s quest for the truth and strongly aligned myself to her principles on capturing the lived experiences of those impacted by war, conflict, and social justice issues. These people, I consider are more qualified to discuss these issues than those of us who sit in the ivory towers of institutions (me included!).

Moreover, I considered how I can be more like Marie and how I can embed her philosophies more so into my own research… whether that’s through researching with communities on the cost-of-living crisis or disseminating my research to students, fellow academics, policymakers, and practitioners. I feel inspired and moving forward, I seek to embody the life and spirit of Marie and thousands of other journalists and academics who work tirelessly to research on and understand the truth to bring forward the narratives of those who are left behind and discarded by society in its mainstream.

Labour’s Winter Fuel Allowance Cut: Austerity 2.0 and the need for De-commodification?

Last week, the Government voted as an overwhelming majority to scrap the winter fuel allowance. This has been met with fierce backlash from critics, particularly Labour MP Zara Sultana who stated her removal of taking part in ‘Austerity 2.0’. Meanwhile, in Prime Minister Questions, Kier Starmer defended the decision by referring to the ’22-billion-pound black hole’ that was left by the former Conservative Government (See Amos, 2024). This policy decision will mean that pensioners and vulnerable social groups across the UK will face a loss of financial support to pay for the ever-rising energy costs, particularly over the coming winter months. The health implications and fears onto those who will be affected were reported widely by critics. For example, Labour MP Rosie Duffield represented her constituents, some of whom were cancer patients who were severely worried about keeping warm this coming winter and relied on the winter fuel allowance as a reliable source of financial support (Lavelle, 2024).

This latest move initiated by Starmer’s Labour Government is primarily justified through the need for temporary acts of austerity, to balance the books and reduce the national debt and deficit which according to Starmer’s speech at the latest Prime Minister’s Questions now sits at over twenty billion.

A fundamental question here is not of the need for action to reduce the national deficit…. rather the question is- who should foot the bill? Latest figures show that within the same time as when the country scraps the winter fuel allowance, According to Race and Jack (2024), major energy companies such as British Gas announced its profits for 2023 has increased ten-fold to £750 million with the profits forecast to soar higher at the end of this year. There are calls by some politicians, including Zara Sultana to introduce a windfall tax that will put a cap on the gross profits gained by energy companies and large-scale businesses, through which these taxes can be put into public infrastructure, services, and spending. A common counterargument here however is how these businesses and corporations will remove themselves from the UK and situate themselves in alternative global markets, that through globalisation and free-market economy principles has become easier.

The scrapping of the winter fuel allowance demonstrates how under economic crisis, it is communities who foot the bill and suffer the consequences of government failure to protect public infrastructure and avoid generating a deficit and national debt. This policy also represents a balancing act between keeping corporations and businesses active players in the free-market economy versus protecting the countries most vulnerable and providing sufficient public infrastructure and utilities. Perhaps there is an alternative way between preserving the markets and re-orienting their purpose back to a public good…

Capitalist markets are led by profiteering… however, through the process of de-commodification, these markets are brought back under state(s) control and are re-oriented to serve a greater public good and social need (Soron & Laxer, 2006; Hilary, 2013). De-commodification turns the modes of production and consumption towards serving a greater public need. Whilst there is profit opportunities for those on the supply side, this is met with serving a greater public need. Essentially, de-commodification removes acts of disempowerment and the dependency of people from the markets and restores the power, much of which is placed back into state control. Perhaps, the model of de-commodification might not work in all contexts, particularly when one considers the intensification of globalisation and geopolitical insecurity, however there should be discussions on de-commodification…. As otherwise, the markets will continue to over-rule the state and communities will continue to pay the price…

References

Amos, O (2024) Starmer and Sunak clash on winter fuel payments at PMQs. BBC News. 11th September. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/live/c303gm7qz3pt {Accessed 13th September 2024}.

Hilary, J (2013) The Poverty of Capitalism: Economic Meltdown and the struggle for what comes next. London: Pluto Press.

Lavelle, D (2024) Winter fuel pay decision ‘brutal’ and could lead to deaths, says Labour MP. The Guardian, 7th September. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/politics/article/2024/sep/07/winter-fuel-pay-decision-brutal-labour-mp-rosie-duffield {Accessed 13th September 2024}.

Race, M., and Jack, S (2024) British Gas sees profits increase ten-fold. BBC News. 15th February. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-68303647#:~:text=British%20Gas%20has%20announced%20its,of%20Russia’s%20invasion%20of%20Ukraine {Accessed 13th September 2024}.

Soron, D., and Laxer, G (2006) De-commodifying Public Life. Peterborough: Broadview Press.

‘A de-construction of the term ‘Cost of Living Crisis’ in recognition of globalism’

The term ‘Cost of Living Crisis’ gets thrown around a lot within everyday discussion, often with little reference to what it means to live under a Cost-of-Living Crisis and how such a crisis is constituted and compares with crises globally. In this blog, I will unpack these questions.

The 2008 Global Financial Crash served as a moment of rupture caused and exacerbated by a series of mini events that unfolded on the world stage…. This partly led to the rise in an annual deficit impacting national growth and debt recovery. Then we entered 2010 when the Coalition Government led by David Cameron and Nick Clegg in the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties implemented a Big Society Agenda, underpinned by an anti-statist ideology and Austerity politics. The legacies of austerity have extensively been highlighted in my own research as communities faced severed cutbacks to social infrastructure and resources, many of whom utilised these resources as a lifeline. Moving forward to the present day in 2024, austerity continues to be alive and well and the national debt has continued to rise…. Events including the Corona Virus Pandemic that started in 2019, Brexit and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have amongst other events served as precipitators to an already existing economic downturn. The rise of interest rates and inflation have been partly led by disruptions to global supply chains, particularly essential and often taken for granted food resources such as wheat and grains. So too has political instability hindering opportunities to invest and grow the local economy contributed towards this economic downturn.

As inflation and interest rates rose, so too did the average cost of living in terms of expenditure and disposable income for both the Working and Middle-Classes. At this point, one can begin to see the emergence of the cost-of-living crisis as being constituted as an issue affecting social class.

The cost-of-living crisis is inherently a term deployed by the Middle Classes as some faced an increase of interest rates on their mortgages in addition to rising costs in the supermarkets. These are valid concerns and the reality and hardship produced under these conditions is not being contested. However, we must not lose sight of the fact that economic downturn and the reality of poverty is nothing new for many working-class communities, who have suffered from disinvestment and austerity, long before the term Cost of Living Crisis came into being.

Equally, we can understand the Cost-of-Living Crisis as being a construction led by Western states, as part of a wider Global North. The separation between the Global North and Global South is bound by geography, but economic growth and its globally recognised position as an emerged or emerging economy. Note that such constructions within themselves are applied by the Global North. Similarly, the Cost-of-Living Crisis is nothing new for these states. The reality of living below a breadline is faced by many of these countries in the Global South and should be understood as a wider systemic and global issue that members of the International Community have a moral obligation to address.

So, when applying terms such as the Cost-of-Living Crisis under every-day discussion, it is necessary to contemplate the historicisms behind such an experience and how life under poverty and hardship is experienced globally and indeed across our own communities. This will enable us to think more critically about this term Cost of Living Crisis, which as it is widely used, faces threat of oversight as to the prevalence and effects of global and local inequalities.

Meet the Team: Liam Miles, Lecturer in Criminology

Hello!

I am Liam Miles, a lecturer in criminology and I am delighted to be joining the teaching team here at Northampton. I am nearing the end of my PhD journey that I completed at Birmingham City University that explored how young people who live in Birmingham are affected by the Cost-of-Living Crisis. I conducted an ethnographic study and spent extensive time at two Birmingham based youth centres. As such, my research interests are diverse and broad. I hold research experience and aspirations in areas of youth and youth crime, cost of living and wider political economy. This is infused with criminological and social theory and qualitative research methods. I am always happy to have a coffee and a chat with any student and colleague who wishes to discuss such topics.

Alongside my PhD, I have completed two solo publications. The first is a journal article in the Sage Journal of Consumer Culture that explored how violent crime that occurs on British University Campuses can be explained through the lens of the Deviant Leisure perspective. An emerging theoretical framework, the Deviant Leisure perspective explores how social harms are perpetuated under the logics and entrenchment of free-market globalised capitalism and neoliberalism. As such, a fundamental source of culpability towards crime, violence and social harm more broadly is located within the logics of neoliberal capitalism under which a consumer culture has arisen and re-cultivated human subjectivity towards what is commonly discussed in the literature as a narcissistic and competitive individualism. My second publication was in an edited book titled Action on Poverty in the UK: Towards Sustainable Development. My chapter is titled ‘Communities of Rupture, Insecurity, and Risk: Inevitable and Necessary for Meaningful Political Change?’. My chapter explored how socio-political and economic moments of rupture to the status quo are necessary for the summoning of political activism; lobbying and subsequent change.

It is my intention to maintain a presence in the publishing field and to work collaboratively with colleagues to address issues of criminal and social justice as they present themselves. Through this, my focus is on a lens of political economy and historical materialism through which to make sense of local and global events as they unfold. I welcome conversation and collaboration with colleagues who are interested in these areas.

Equally, I am committed to expanding my knowledge basis and learning about the vital work undertaken by colleagues across a breadth of subject areas, where it is hoped we can learn from one another.

I am thoroughly looking forward to meeting everyone and getting to learn more!