Family life in Tenerife versus the UK

I have recently been on a family holiday with our toddler to Tenerife. We began the journey by getting to an airport in the UK. Whilst there the security checks were done for families alongside everyone else. Toddlers were required to get out of their prams, to have their shoes taken off and could not hold onto their toys. The security seemed relatively tight as my hands were swabbed, my toddler was searched with a security stick and the small volume of water that he was allowed was also swabbed.

Whilst arriving and departing via the airport in Tenerife the security allocated a separate quieter section of space for families, this seemed far more relaxed, staff were smiling and dared to say ‘hola’ and ‘hello’. There were no additional checks and a toddler cup of water was allowed. Some staff were also making a deliberate attempt to identify the names of babies, toddlers and children from boarding passes or passports to be able to greet them by their names with waves and smiles.

Whilst on holiday I could be forgiven for thinking that we were royalty whilst pushing a pram and toddler around the streets. As pedestrians always had the right of way, whenever there is a road to cross, the cars must stop due to zebra-like crossings marking on the ground. There are also plenty of playgrounds and toilets and plenty of opportunity for play outdoors in sea and sand.

Whilst at home in Birmingham (UK) there are far less zebra crossings and on quite a few occasions cars have failed to stop at zebra crossings whilst I have been waiting with a pram and toddler. Baby and toddler swimming pools also seem to be difficult to access due to locations and restrictions on pool opening time frames. There are parks but I have never seen a park within a shopping centre like I did in Tenerife. Despite the UK becoming quite cold in the winter, the ability to access free indoor play during winter time also seems to be a privilege, rather than a given. Whilst there are some fabulous playgroups and library sessions for babies and toddlers, sometimes establishments promoting themselves as ‘family friendly’ places do not always feel friendly to toddlers at all. This is especially the case if toddlers are required to adhere to adult informal rules, such as not touching things or making loud noise. As some how toddlers trying to explore their world are labelled by some as ‘terrible’ at ‘two’ (see below poem by Holly McNish).

Whilst I have no idea about the education system in Tenerife, these experiences did leave me reflecting on the provision of mainstream education for babies, toddlers and children in the UK. In comparison to countries such as Finland, some mainstream UK education settings are often critiqued for limiting play, time spent in the outdoors, creativity and freedom to think (Dorling and Koljonen, 2020). The popularity of European influenced Montessori nurseries and Forest Schools in the UK seem to indicate that some parents do want something different for children. Whilst on mention of difference, UK mainstream educational approaches to difference seem to be about an assimilation type of inclusivity and diversity, rather than celebrating and learning from the variety of UK cultures. For instance, it seems “marvelous” that if attending mainstream schools in the UK some Romany gypsies are required to fit the restrictive and disciplinarian like school mould, i.e., of shutting up and sitting down (see Good English by Tawona Sithole) or sitting straight and not talking (see Julia Donaldson’s children’s book: The Snail and the Whale). Yet there is little (if any) acknowledgment of how some Romany have an educating culture of fostering independence, voice, freedom and creativity through plenty of outdoor play, roaming around and human interaction is a huge positive. Dorling and Koljonen (2020) state that investment in children and family support is incredibly beneficial for society, as well as families. The reflection above left me thinking that more or something different could be done.

Reference:

Dorling, D and Koljonen, A. (2020) Finntopia : What We Can Learn from the World’s Happiest Country. Newcastle upon Tyne: Agenda Publishing.

Britain’s new relationship with America…Some thoughts

Within the coming weeks, Keir Starmer is due to meet Donald Trump and in doing so has offered an interesting view into the complexities of managing diplomacy in the modern age. Whilst the UK and US work collaboratively through bi-lateral trade agreements, and national security collaborations, the change in power structures within the UK and USA marks significant ideological difference that can arguably present a myriad of implications for both countries and for those countries who are implicated by these relations between Britain and America. In this blog, I will outline some of the factors that ought to be considered as we fast-approach this new age of international relations.

It can be understood that Starmer meeting Trump, despite some ideological difference is rooted in a pragmatic diplomacy approach and for what some might say is for the greater good. In an age of continual risk and uncertainty, allyship across nations has seldom been more necessary nor consolidated. On addressing issues including climate change, national security, trade agreements within a post-Brexit adversity, the relationship between America and Britain I sense is being foregrounded by Starmer’s Labour Government.

Moreover, I consider that Starmer should tread carefully and not appear globally as though he is too strongly aligned with Trump’s policies, especially on foreign policy. This mistake was once made by Tony Blair, following the New Beginnings movement after 9/11. It is essential that whilst we maintain good relations with America, this does not come at a cost to our own sovereignty and influence on global issues. I see here an opportunity for Starmer to re-build Britain’s place on the global stage. Despite this as what some strategists might call a ‘bigger picture’, it goes without saying that Starmer may face backlash from his peers based on his willingness to enter a liaison with Trump’s Government. For many inside and outside of the Labour Party, the politics of Trump are considered dangerous, regressive, and ideologically dumbfounded. I happen to agree with much of these sentiments, and I think there is a risk for Starmer… that will later develop into a dilemma. This dilemma will be between appeasing the party majority and those who hold traditional Labour values in place of moving further into the clutches of the far right, emboldened by neoliberalism. It is no secret however that the Labour party has entered a dangerous liaison with neoliberalism and has alienated many traditional Labour voters and has offered no real political alternative.

Considering this, I sense an apprehension is in the air regarding Starmer’s relationship building with America and Donald Trump, that some might argue might be more counter-productive than good. Starmer must demonstrate political pragmatism and arguably the impact of this government and the governments to come will weigh on these relations… Albeit time will tell in determining how these future relations are mapped out.

What makes a good or bad society?: X

As part of preparing for University, new students were encouraged to engage in a number of different activities. For CRI1009 Imagining Crime, students were invited to contribute a blog on the above topic. These blog entries mark the first piece of degree level writing that students engaged with as they started reading for their BA (Hons) Criminology. With the students’ agreement these thought provoking blogs have been brought together in a series which we will release over the next few weeks.

A society can be defined as a certain number of people living together within a community, of which, all of humanity contribute toward in various ways. Therefore, to accurately determine whether the very society we live in is plainly good or bad is practically impossible. This is due to the sheer number of factors that intertwine to breed what we know as a society, such as beliefs, language, social norms and various other elements. Having said this, it is possible to determine what makes a society better, for example equality for all that present equal chance and opportunity for every human, regardless of age, gender or race of which can be evidenced in the world we live in today. Examples of this include the Equality Act of 2010, that required public bodies to prove how their chosen policies have affected people with protected characteristics. This provides evidence that suggests the society we live within is indeed good, as this alludes to the idea that all who contain protected characteristics are catered for as their needs may require, ideally removing any feeling of prejudice or hardship for those with protected characteristics.

However, there are components that make a society worse, such as prejudices, these can be based on people’s race, gender, age, etc. Prejudice can be described as someone obtaining a preconceived opinion that is not based on reason, reality or even from an opinion that is often harmful and negative. This can derive from harmful stereotypes or even family upbringing, meaning natural tensions and aggression appear within society, of which, appear within our very own. Despite actions taken to combat such, it is indisputable to argue that racism and sexism still very much plague humanity and therefore society, potentially causing the conclusion that our society is in fact bad.

Overall, the idea that our society can be plainly labelled as good or bad is vastly naïve. However, this is not to suggest that elements within our society are good, such as equality being more and more evident within our society, meaning equal opportunity and chance for humanity that is unarguably positive. On the contrary, the very fact that prejudices still plague society to this very day, highlights the worst parts of society, concluding that our society is neither good nor bad, but rather a combination of the two thus creating a complex system we know today as, our society.

25 years of Criminology

When the world was bracing for a technological winter thanks to the “millennium bug” the University of Northampton was setting up a degree in Criminology. Twenty-five years later and we are reflecting on a quarter of a century. Since then, there have been changes in the discipline, socio-economic changes and wider changes in education and academia.

The world at the beginning of the 21st century in the Western hemisphere was a hopeful one. There were financial targets that indicated a raising level of income at the time and a general feeling of a new golden age. This, of course, was just before a new international chapter with the “war on terror”. Whilst the US and its allies declared the “war on terror” decreeing the “axis of evil”, in Criminology we offered the module “Transnational Crime” talking about the challenges of international justice and victor’s law.

Early in the 21st century it became apparent that individual rights would take centre stage. The political establishment in the UK was leaving behind discussions on class and class struggles and instead focusing on the way people self-identify. This ideological process meant that more Western hemisphere countries started to introduce legal and social mechanisms of equality. In 2004 the UK voted for civil partnerships and in Criminology we were discussing group rights and the criminalisation of otherness in “Outsiders”.

During that time there was a burgeoning of academic and disciplinary reflection on the way people relate to different identities. This started out as a wider debate on uniqueness and social identities. Criminology’s first cousin Sociology has long focused on matters of race and gender in social discourse and of course, Criminology has long explored these social constructions in relation to crime, victimisation and social precipitation. As a way of exploring race and gender and age we offered modules such as “Crime: Perspectives of Race and Gender” and “Youth, Crime and the Media”. Since then we have embraced Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality and embarked on a long journey for Criminology to adopt the term and explore crime trends through an increasingly intersectional lens. Increasingly our modules have included an intersectional perspective, allowing students to consider identities more widely.

The world’s confidence fell apart when in 2008 in the US and the UK financial institutions like banks and other financial companies started collapsing. The boom years were replaced by the bust of the international markets, bringing upheaval, instability and a lot of uncertainty. Austerity became an issue that concerned the world of Criminology. In previous times of financial uncertainty crime spiked and there was an expectation that this will be the same once again. Colleagues like Stephen Box in the past explored the correlation of unemployment to crime. A view that has been contested since. Despite the statistical information about declining crime trends, colleagues like Justin Kotzé question the validity of such decline. Such debates demonstrate the importance of research methods, data and critical analysis as keys to formulating and contextualising a discipline like Criminology. The development of “Applied Criminological Research” and “Doing Research in Criminology” became modular vehicles for those studying Criminology to make the most of it.

During the recession, the reduction of social services and social support, including financial aid to economically vulnerable groups began “to bite”! Criminological discourse started conceptualising the lack of social support as a mechanism for understanding institutional and structural violence. In Criminology modules we started exploring this and other forms of violence. Increasingly we turned our focus to understanding institutional violence and our students began to explore very different forms of criminality which previously they may not have considered. Violence as a mechanism of oppression became part of our curriculum adding to the way Criminology explores social conditions as a driver for criminality and victimisation.

While the world was watching the unfolding of the “Arab Spring” in 2011, people started questioning the way we see and read and interpret news stories. Round about that time in Criminology we wanted to break the “myths on crime” and explore the way we tell crime stories. This is when we introduced “True Crimes and Other Fictions”, as a way of allowing students and staff to explore current affairs through a criminological lens.

Obviously, the way that the uprising in the Arab world took charge made the entire planet participants, whether active or passive, with everyone experiencing a global “bystander effect”. From the comfort of our homes, we observed regimes coming to an end, communities being torn apart and waves of refugees fleeing. These issues made our team to reflect further on the need to address these social conditions. Increasingly, modules became aware of the social commentary which provides up-to-date examples as mechanism for exploring Criminology.

In 2019 announcements began to filter, originally from China, about a new virus that forced people to stay home. A few months later and the entire planet went into lockdown. As the world went into isolation the Criminology team was making plans of virtual delivery and trying to find ways to allow students to conduct research online. The pandemic rendered visible the substantial inequalities present in our everyday lives, in a way that had not been seen before. It also made staff and students reflect upon their own vulnerabilities and the need to create online communities. The dissertation and placement modules also forced us to think about research outside the classroom and more importantly outside the box!

More recently, wars in Europe, the Middle East, Africa and Asia have brought to the forefront many long posed questions about peace and the state of international community. The divides between different geopolitical camps brought back memories of conflicts from the 20th century. Noting that the language used is so old, but continues to evoke familiar divisions of the past, bringing them into the future. In Criminology we continue to explore the skills required to re-imagine the world and to consider how the discipline is going to shape our understanding about crime.

It is interesting to reflect that 25 years ago the world was terrified about technology. A quarter of a century later, the world, whilst embracing the internet, is worriedly debating the emergence of AI, the ethics of using information and the difference between knowledge and communication exchanges. Social media have shifted the focus on traditional news outlets, and increasingly “fake news” is becoming a concern. Criminology as a discipline, has also changed and matured. More focus on intersectional criminological perspectives, race, gender, sexuality mean that cultural differences and social transitions are still significant perspectives in the discipline. Criminology is also exploring new challenges and social concerns that are currently emerging around people’s movements, the future of institutions and the nature of society in a global world.

Whatever the direction taken, Criminology still shines a light on complex social issues and helps to promote very important discussions that are really needed. I can be simply celebratory and raise a glass in celebration of the 25 years and in anticipation of the next 25, but I am going to be more creative and say…

To our students, you are part of a discipline that has a lot to say about the world; to our alumni you are an integral part of the history of this journey. To those who will be joining us in the future, be prepared to explore some interesting content and go on an academic journey that will challenge your perceptions and perspectives. Radical Criminology as a concept emerged post-civil rights movements at the second part of the 20th century. People in the Western hemisphere were embracing social movements trying to challenge the established views and change the world. This is when Criminology went through its adolescence and entered adulthood, setting a tone that is both clear and distinct in the Social Sciences. The embrace of being a critical friend to these institutions sitting on crime and justice, law and order has increasingly become fractious with established institutions of oppression (think of appeals to defund the police and prison abolition, both staples within criminological discourse. The rigour of the discipline has not ceased since, and these radical thoughts have led the way to new forms of critical Criminology which still permeate the disciplinary appeal. In recent discourse we have been talking about radicalisation (which despite what the media may have you believe, can often be a positive impetus for change), so here’s to 25 more years of radical criminological thinking! As a discipline, Criminology is becoming incredibly important in setting the ethical and professional boundaries of the future. And don’t forget in Criminology everyone is welcome!

What makes a good or bad society?: IX

As part of preparing for University, new students were encouraged to engage in a number of different activities. For CRI1009 Imagining Crime, students were invited to contribute a blog on the above topic. These blog entries mark the first piece of degree level writing that students engaged with as they started reading for their BA (Hons) Criminology. With the students’ agreement these thought provoking blogs have been brought together in a series which we will release over the next few weeks.

By definition, a society is a crowd of people living together in a community. So when it comes to discussing a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ society we must consider if everybody in the community follows the standard of social norms that are expected and what each community demands as the list of standardised norms may differ. In modern day British societies, it can sometimes be difficult to decide whether we live in a good or bad society. This can be difficult for reasons such as politics, law and crime. Some may decide our society is good because they believe our government is fair and they reap the benefits of those higher up whereas others may deem our society as bad because the government is unfair, and they are at a disadvantage. I would say there are 5 main qualities to a good society: Equality, freedom, empowerment, opportunity and education. Equality is an important factor for a good society as it makes sure people are treated with the same levels of respect and dignity as everyone else and that the differences they may have are celebrated and not shunned. As well as this, freedom is important as it allows people to create lives full of purpose, meaning and success and gives people the ability to flourish and thrive. Similarly, empowerment is important because it promotes both equality and freedom while reducing inequality by enabling the individuals who have been discriminated against to take charge and participate as a member of society. In addition to this, opportunity is equally as important because it enables individuals to have a fair chance to achieve their potential, whether this be achieving their dream job/career or being successful in education. Finally, education is an important characteristic to a good society because it promotes economic growth within our society, provides young people with career paths and ensures a great deal of personal development. Without these key fundamentals in a society, it can lead to high crime rates in certain categories such as antisocial behaviour, hate crime, violent crime and theft. To avoid a spike in crime rates it is essential a society works on these values. While its easy to talk about what makes a good society it is just as important to be aware of what makes a bad society. Each individual will believe it takes different characteristics to make a society bad, but in my opinion, I believe there are 5 specific qualities to a bad society. If a society contains any of the following, it can arguably be classified as a bad society: inequality, lack of justice, discrimination, poor education and cultural oppression. Not only will a society with these values be ‘bad’ but it creates an altered view on what the socially normative way of life is.

Unfortunately, in today’s society each of the crucial qualities to have a ‘good’ society can never be guaranteed. Even in modern-day society we still see each of these qualities shut down by racism, sexism and ableism. So with all of this information considered I believe there can never be a definitive answer to the question of “Do we live in a good or bad society”.

SUPREME COURT VISIT WITH MY CRIMINOLOGY SQUAD!

Author: Dr Paul Famosaya

This week, I’m excited to share my recent visit to the Supreme Court in London – a place that never fails to inspire me with its magnificent architecture and rich legal heritage. On Wednesday, I accompanied our final year criminology students along with my colleagues Jes, Liam, and our department head, Manos, on what proved to be a fascinating educational visit. For those unfamiliar with its role, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom stands at the apex of our legal system. It was established in 2009, and serves as the final court for all civil cases in the UK and criminal cases from England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. From a criminological perspective, this institution is particularly significant as it shapes the interpretation and application of criminal law through precedent-setting judgments that influence every level of our criminal justice system

7:45 AM: Made it to campus just in the nick of time to join the team. Nothing starts a Supreme Court visit quite like a dash through Abington’s morning traffic!

8:00 AM: Our coach is set to whisk us away to London!

Okay, real talk – whoever designed these coach air conditioning systems clearly has a vendetta against warm-blooded academics like me! 🥶 Here I am, all excited about the visit, and the temperature is giving me an impromptu lesson in ‘cry’ogenics. But hey, nothing can hold us down!.

Picture: Inside the coach where you can spot the perfect mix of university life – some students chatting about the visit, while others are already practising their courtroom napping skills 😴

There’s our department Head of Departmen Manos, diligently doing probably his fifth headcount 😂. Big boss is channelling his inner primary school teacher right now, armed with his attendance sheet and pen and all. And yes, there’s someone there in row 5 I think, who’s already dozed off 🤦🏽♀️ Honestly, can’t blame them, it’s criminally early!

9:05 AM The dreaded M1 traffic

Sometimes these slow moments give us the best opportunities to reflect. While we’re crawling through, my mind wanders to some of the landmark cases we’ll be discussing today. The Supreme Court’s role in shaping our most complex moral and legal debates is fascinating – take the assisted dying cases for instance. These aren’t just legal arguments; they’re profound questions about human dignity, autonomy, and the limits of state intervention in deeply personal decisions. It’s also interesting to think about how the evolution of our highest court reflects (or sometimes doesn’t reflect) the society it serves. When we discuss access to justice in our criminology lectures, we often talk about how diverse perspectives and lived experiences shape legal interpretation and decision-making. These thoughts feel particularly relevant as we approach the very institution where these crucial decisions are made.

The traffic might be testing our patience, but at least it’s giving us time to really think about these issues.

10:07 AM – Arriving London – The stark reality of London’s inequality hits you right here, just steps from Hyde Park.

Honestly, this is a scene that perfectly summarises the deep social divisions in our society – luxury cars pulling up to the Dorchester where rooms cost more per night than many people earn in a month, while just meters away, our fellow citizens are forced to make their beds on cold pavements. As a criminologist, these scenes raise critical questions about structural violence and social harms. When we discuss crime and justice in our lectures, we often talk about root causes. Here they are, laid bare on London’s streets – the direct consequences of austerity policies, inadequate mental health support, and a housing crisis that continues to push more people into precarity. But as we say in the Nigerian dictionary of life lessons – WE MOVE!! 🚀

10:31 AM Supreme Court security check time

Security check time, and LISTEN to how they’re checking our students’ water bottles! The way they’re examining those drinks is giving: Nah this looks suspicious 🤔

So there I am, breezing through security like a pro (years of academic conferences finally paying off!). Our students follow suit, all very professional and courtroom-ready. But wait for it… who’s that getting the extra-special security attention? None other than our beloved department head Manos! 😂

The security guard’s face is priceless as he looks through his bags back and forth. Jes whispers to me ‘is Manos trying to sneak in something into the supreme court?’ 😂 Maybe they mistook his collection of snacks for contraband? Or perhaps his stack of risk assessment forms looked suspicious? 😂 There he is, explaining himself, while the rest of us try (and fail) to suppress our giggles. He is a free man after all.

10: 44AM Right so first stop, – Court Room 1.

Our tour guide provided an overview of this institution, established in 2009 when it took over from the House of Lords as the UK’s highest court. The transformation from being part of the legislature to becoming a physically separate supreme court marked a crucial step in the separation of powers in the country’s legislation. There’s something powerful about standing in this room where the Justices (though they usually sit in panels of 5 or 7) make decisions. Each case mentioned had our criminology students leaning in closer, seeing how theoretical concepts from their modules materialise in this very room.

10:59 AM Moving into Court 2, the more modern one!

After exploring Courtroom 1, we moved into Court Room 2, and yep, I also saw the contrast! And apparently, our guide revealed, this is the judges’ favourite spot to dispense justice – can’t blame them, the leather chairs felt lush tbh!

Speaking of judges, give it up for our very own Joseph Buswell who absolutely nailed it when the guide asked about Supreme Court proceedings! 👏🏾 As he correctly pointed out, while we have 12 Supreme Court Justices in total, they don’t all pile in for every case. Instead, they work in panels of 3 or 5 (always keeping it odd to avoid those awkward tie situations). 👏🏾 And what makes Court Room 2 particularly significant for public access to justice the cameras and modern AV equipment which allow for those constitutional and legal debates to be broadcast to the nation. Spot that sneaky camera right at the top? Transparency level: 100% I guess!

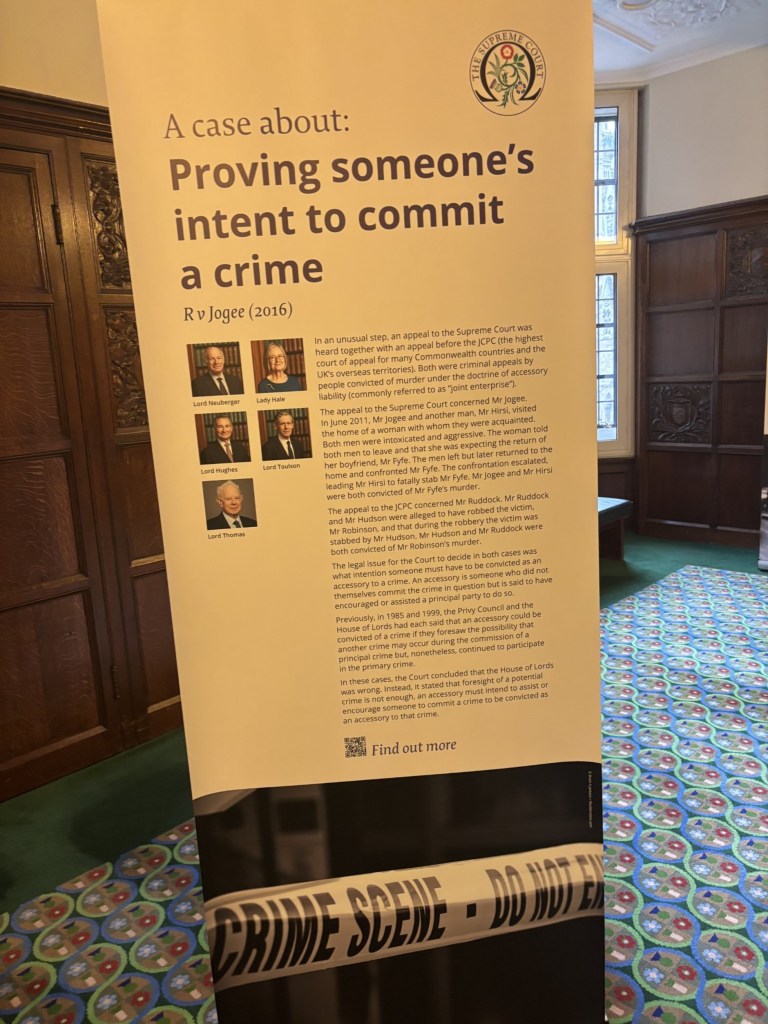

The exhibition area

The exhibition space was packed with rich historical moments from the Supreme Court’s journey. Among the displays, I found myself pausing at the wall of Justice portraits. Let’s just say it offered quite the visual commentary on our judiciary’s journey towards representation…

Beyond the portraits, the exhibition showcased crucial stories of landmark judgments that have shaped our legal landscape. Each case display reminded us how crucial diverse perspectives are in the interpretation and application of law in our multicultural society.

11: 21AM Moving into Court 3, home of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC)

The sight of those Commonwealth flags tells a powerful story about the evolution of colonial legal systems and modern voluntary jurisdiction. Our guide explained how the JCPC continues to serve as the highest court of appeal for various independent Commonwealth countries. The relationship between local courts in these jurisdictions and the JCPC raises critical questions about legal sovereignty and judicial independence and the students were particularly intrigued by how different legal systems interact within this framework – with each country maintaining its own laws and legal traditions, yet looks to London for final decisions.

Breaktime!!!!

While the group headed out in search of food, Jes and I were bringing up the rear, catching up after the holiday and literally SCREAMING about last year’s Winter Wonderland burger and hot dog prices (“£7.50 for entry too? In this Keir Starmer economy?!😱”). Anyway, half our students had scattered – some in search of sustenance, others answering the siren call of Zara (because obviously, a Supreme Court visit requires a side of retail therapy 😉).

But here’s the moment that had us STUNNED – right there on the street, who should come power-walking past but Sir Chris Whitty himself! 😱 England’s Chief Medical Officer was on a mission, absolutely zooming past us like he had an urgent SAGE meeting to get to 🏃♂️. That man moves with PURPOSE! I barely had time to nudge Jes before he’d disappeared. One second he was there, the next – gone! Clearly, those years of walking to press briefings during the pandemic have given him some serious speed-walking skills! 👀

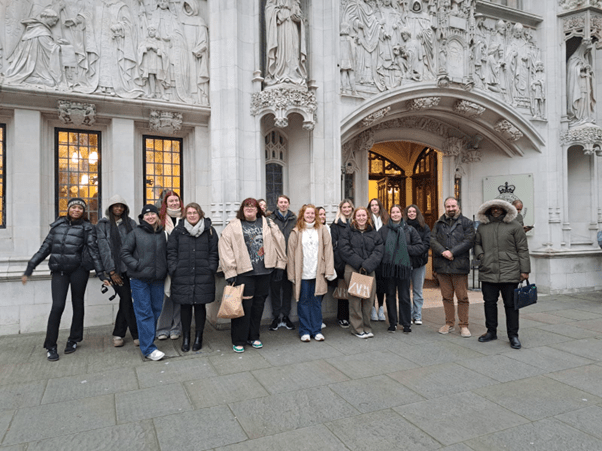

3:30 PM – Group Photo!

Looking at these final year criminology students in our group photo though! Even with that criminal early morning start (pun intended 😅), they made it through the whole Supreme Court experience! Big shout out to all of them 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾 Can you spot me? I’m the one on the far right looking like I’m ready for Arctic exploration (as Paula mentioned yesterday), not London weather! 🥶 Listen, my ancestral thermometer was not calibrated for this kind cold today o! Had to wrap up in my hoodie like I was jollof rice in banana leaves – and you know we don’t play with our jollof! 😤

4:55 PM Heading Back To NN

On the journey back to NN, while some students dozed off (can’t blame them – legal learning is exhausting!), I found myself reflecting on everything we’d learned. From the workings of the highest court in our land to the stark realities of social inequality we witnessed near Hyde Park, today brought our theoretical classroom discussions into sharp focus. Sitting here, watching London fade into the distance, I’m reminded of why these field trips are so crucial for our students’ understanding of justice, law, and society.

Listen, can we take a moment to appreciate our driver though?! Navigating that M1 traffic like a BOSS, and getting us back safe and sound! The real MVP of the day! 👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

And just like that, our Supreme Court trip comes to an end. From early morning rush to security check shenanigans, from spotting Chief Medical Officer on the streets to freezing our way through legal history – what a DAY!

To my amazing final years who made this trip extra special – y’all really showed why you’re the future of criminology! 👏🏾 Special shoutout to Manos (who can finally put down his attendance sheet 😂), Jes, and Liam for being the dream team! And to London… boyyyy, next time PLEASE turn up the heat! 🥶

As we all head our separate ways, some students were still chatting about the cases we learned about (while others were already dreaming about their beds 😴), In all, I can’t help but smile – because days like these? This is what university life is all about!

Until our next adventure… your frozen but fulfilled criminology lecturer, signing off! 🙌

What makes a good or bad society?: VIII

As part of preparing for University, new students were encouraged to engage in a number of different activities. For CRI1009 Imagining Crime, students were invited to contribute a blog on the above topic. These blog entries mark the first piece of degree level writing that students engaged with as they started reading for their BA (Hons) Criminology. With the students’ agreement these thought provoking blogs have been brought together in a series which we will release over the next few weeks.

Fundamentally, the requirements for a ‘good’ society should consist of several characteristics that contribute to a positive quality of life for all members of the community. There should be a basis in equality, fair judgment, and the ability for all people who are a part of that society to live without undue struggle or unnecessary discomfort, be it financial, emotional or physical. There are a lot of reasons why a society might be good, or bad, and fixing any one problem will not automatically allow us to call ourselves good, but any progress can be positive and may take us closer.

There are large steps towards equality that we as a society have taken in the last century, however this progress is not sustainable when there are many in positions of power who have no interest in changing the status quo. According to the European Commission, less than one in ten CEOs of major companies are women, and women are over represented in particular types of career, which is known as sectoral segregation. This leads to many viewing these sectors as overly feminine, and while this isn’t necessarily true, and shouldn’t affect how valued those careers are, careers viewed as feminine are systemically undervalued, and consistently lead to judgment for those choosing to follow those paths, leaving them underpaid and overworked. In 2021 there was still a gender pay gap of 12.7% in the European Union, with women on average earning almost 13% less than men hourly. Can a society that undervalues over half of its members truly be a good society?

In addition to this, there is a cycle of racial discrimination within this society’s judgment system. With systemic racism ingrained in society for years before legislation was introduced to prevent discrimination in terms of housing and hiring, the UK’s police force contained rampant racial bias for years, which perpetuates even today. Black people in the UK are stopped on the street up to seven times more frequently than white people. There is an undue fear within the public that black people are more dangerous, that they are more likely to commit crime, and statistics that seem to prove this correct are often taken out of context, or supplied without consideration for social factors which may cause this. There is often an aspect of moral panic, whereby the media and other agents of social control use isolated events to incite fear of a particular community, and this causes a dangerous cycle of self fulfilling prophecy, where that community appears to act as expected. After all, if an entire group of people are going to be treated badly, regardless of their actions, does it make any difference if they fulfil our expectations or not?

True equality within any society is impossible, as humans we have natural differences which prevent us from being exactly the same. If men and women participated equally in all sports, there would likely be more injuries simply from biological advantages. If everyone earned the same, and class differences did not exist, there would be no motivation or reward for going above and beyond in the search for success and improvement, and society would remain stagnant. However, we are failing in our most basic duty to protect people from unfair discrimination, and at least offer the opportunity to try for success. Many careers considered ‘too feminine’ to hold true value in society include those in education or healthcare, which are vital in ensuring the next generation can be better than we are, and in maintaining the wellbeing of current members of the community. We should be using the media to dismantle these prejudices, rather than using it to target other groups and spread fear and misinformation. These issues may persist due to a lack of awareness in the wider community, or maybe they exist due to higher powers encouraging that society remain as it is, with them benefiting at the cost of others suffering. I would prefer to assume ignorance over malice, but neither is an excuse. Until we can claim to be as equal a society as it is possible to be, respecting the contributions women offer to society and treating them with the respect they deserve, and not treating a different skin colours as a marker for antisocial behaviour, just to name a few, I cannot claim to live in a truly good society.

Criminology for all (including children and penguins)!

As a wise woman once wrote on this blog, Criminology is everywhere! a statement I wholeheartedly agree with, certainly my latest module Imagining Crime has this mantra at its heart. This Christmas, I did not watch much television, far more important things to do, including spending time with family and catching up on reading. But there was one film I could not miss! I should add a disclaimer here, I’m a huge fan of Wallace and Gromit, so it should come as no surprise, that I made sure I was sitting very comfortably for Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl. The timing of the broadcast, as well as it’s age rating (PG), clearly indicate that the film is designed for family viewing, and even the smallest members can find something to enjoy in the bright colours and funny looking characters. However, there is something far darker hidden in plain sight.

All of Aardman’s Wallace and Gromit animations contain criminological themes, think sheep rustling, serial (or should that be cereal) murder, and of course the original theft of the blue diamond and this latest outing was no different. As a team we talk a lot about Public Criminology, and for those who have never studied the discipline, there is no better place to start…. If you don’t believe me, let’s have a look at some of the criminological themes explored in the film:

Sentencing Practice

In 1993, Feathers McGraw (pictured above) was sent to prison (zoo) for life for his foiled attempt to steal the blue diamond (see The Wrong Trousers for more detail). If we consider murder carries a mandatory life sentence and theft a maximum of seven years incarceration, it looks like our penguin offender has been the victim of a serious miscarriage of justice. No wonder he looks so cross!

Policing Culture

In Vengeance Most Fowl we are reacquainted with Chief Inspector Mcintyre (see The Curse of the Were-Rabbit for more detail) and meet PC Mukherjee, one an experienced copper and the other a rookie, fresh from her training. Leaving aside the size of the police force and the diversity reflected in the team (certainly not a reflection of policing in England and Wales), there is plenty more to explore. For example, the dismissive behaviour of Mcintyre toward Mukherjee’s training. learning is not enough, she must focus on developing a “copper’s gut”. Mukherjee also needs to show reverence toward her boss and is regularly criticised for overstepping the mark, for instance by filling the station with Wallace’s inventions. There is also the underlying message that the Chief Inspector is convinced of Wallace’s guilt and therefore, evidence that points away from should be ignored. Despite this Mukherjee retains her enthusiasm for policing, stays true to her training and remains alert to all possibilities.

Prison Regime

The facility in which Feathers McGraw is incarcerated is bleak, like many of our Victorian prisons still in use (there are currently 32 in England and Wales). He has no bedding, no opportunities to engage in meaningful activities and appears to be subjected to solitary confinement. No wonder he has plenty of time and energy to focus on escape and vengeance! We hear the fear in the prison guards voice, as well as the disparaging comments directed toward the prisoner. All in all, what we see is a brutal regime designed to crush the offender. What is surprising is that Feathers McGraw still has capacity to plot and scheme after 31 years of captivity….

Mitigating Factors

Whilst Feathers McGraw may be the mastermind, from prison he is unable to do a great deal for himself. He gets round this by hacking into the robot gnome, Norbot. But what of Norbot’s free will, so beloved of Classical Criminology? Should he be held culpable for his role or does McGraw’s coercion and control, renders his part passive? Without, Norbot (and his clones), no crime could be committed, but do the mitigating factors excuse his/their behaviour? Questions like this occur within the criminal justice system on a regular basis, admittedly not involving robot gnomes, but the part played in criminality by mental illness, drug use, and the exploitation of children and other vulnerable people.

And finally:

Above are just some of the criminological themes I have identified, but there are many others, not least what appears to be Domestic Abuse, primarily coercive control, in Wallace and Gromit’s household. I also have not touched upon the implicit commentary around technology’s (including AI’s) tendency toward homogeneity. All of these will keep for classroom discussions when we get back to campus next week 🙂