Is Criminology Up to Speed with AI Yet?

On Tuesday, 20th June 2023, the Black Criminology Network (BCN) together with some Criminology colleagues were awarded the Culture, Heritage, and Environment Changemaker of the Year Award 2023. The University of Northampton Changemaker Awards is an event showcasing, recognising, and celebrating some of the key success and achievements of staff, students, graduates, and community initiatives.

For this award, the BCN, and the team held webinars with a diverse audience from across the UK and beyond to mark the Black History Month. The webinars focused on issues around the ‘criminalisation of young Black males, the adultification of Black girls, and the role of the British Empire in the marking of Queen Elizabeth’s Jubilee.’. BCN was commended for ‘creating a rare and much needed learning community that allows people to engage in conversations, share perspectives, and contextualise experiences.’ I congratulate the team!

The award of the BCN and Criminology colleagues reflects the effort and endeavour of Criminologists to better society. Although Criminology is considered a young discipline, the field and the criminal justice system has always demonstrated the capacity to make sense of criminogenic issues in society and theorise about the future of crime and its administration/management. Radical changes in crime administration and control have not only altered the pattern of some crime, but criminality and human behaviour under different situations and conditions. Little strides such as the installation and use of fingerprints, DNA banks, and CCTV cameras has significantly transformed the discussion about crime and crime control and administration.

Criminologist have never been shy of reviewing, critiquing, recommending changes, and adapting to the ever changing and dynamic nature of crime and society. One of such changes has been the now widely available artificial intelligence (AI) tools. In my last blog, I highlighted the morality of using AI by both academics and students in the education sector. This is no longer a topic of debate, as both academics and students now use AI in more ways than not, be it in reading, writing, and formatting, referencing, research, or data analysis. Advance use of various types of AI has been ongoing, and academics are only waking up to the reality of language models such as Bing AI, Chat GPT, Google Bard. For me, the debate should now be on tailoring artificial intelligence into the curriculum, examining current uses, and advancing knowledge and understanding of usage trends.

For CriminologistS, teaching, research, and scholarship on the current advances and application of AI in criminal justice administration should be prioritised. Key introductory criminological texts including some in press are yet to dedicate a chapter or more to emerging technologies, particularly, AI led policing and justice administration. Nonetheless, the use of AI powered tools, particularly algorithms to aid decision making by the police, parole, and in the courts is rather soaring, even if biased and not fool-proof. Research also seeks to achieve real-world application for AI supported ‘facial analysis for real-time profiling’ and usage such as for interviews at Airport entry points as an advanced polygraph. In 2022, AI led advances in the University of Chicago predicted with 90% accuracy, the occurrence of crime in eight cities in the US. Interestingly, the scholars involved noted a systemic bias in crime enforcement, an issue quite common in the UK.

The use of AI and algorithms in criminal justice is a complex and controversial issue. There are many potential benefits to using AI, such as the ability to better predict crime, identify potential offenders, and make more informed decisions about sentencing. However, there are also concerns about the potential for AI to be biased or unfair, and to perpetuate systemic racism in the criminal justice system. It is important to carefully consider the ethical implications of using AI in criminal justice. Any AI-powered system must be transparent and accountable, and it must be designed to avoid bias. It is also important to ensure that AI is used in a way that does not disproportionately harm marginalized communities. The use of AI in criminal justice is still in its early stages, but it has the potential to revolutionize the way we think about crime and justice. With careful planning and implementation, AI can be used to make the criminal justice system fairer and more effective.

AI has the potential to revolutionize the field of criminology, and criminologists need to be at the forefront of this revolution. Criminologists need to be prepared to use AI to better understand crime, to develop new crime prevention strategies, and to make more informed decisions about criminal justice. Efforts should be made to examine the current uses of AI in the field, address biases and limitations, and advance knowledge and understanding of usage trends. By integrating AI into the curriculum and fostering a critical understanding of its implications, Criminologists can better equip themselves and future generations with the necessary tools to navigate the complex landscape of crime and justice. This, in turn, will enable them to contribute to the development of ethical and effective AI-powered solutions for crime control and administration.

Refugee Week 2023

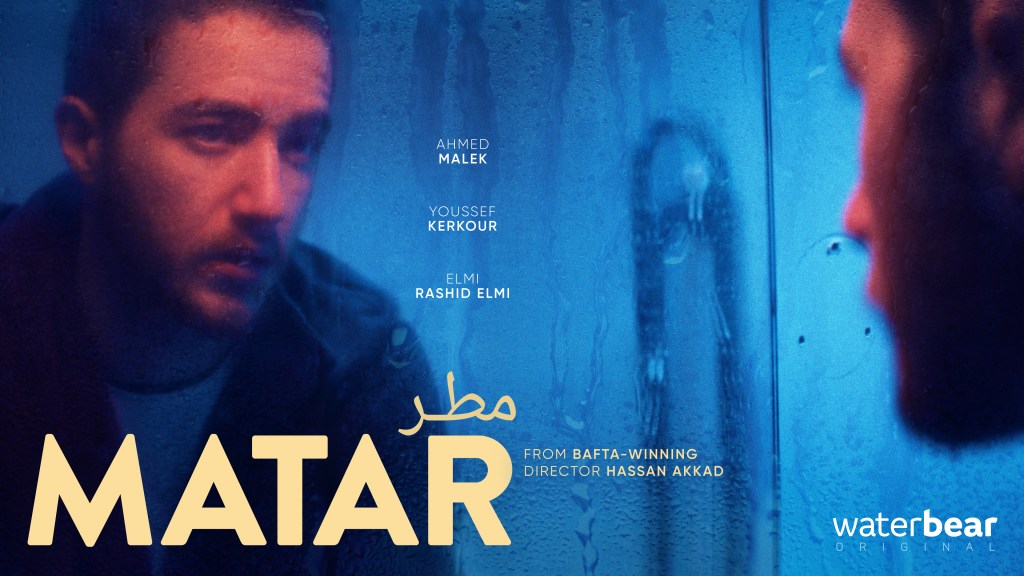

Monday 19th June commences the 2023 Refugee Week and this year’s theme is compassion, a quality we have seen little of in Fortress Europe policy and practice this year. As many of you will know, Jessica James and I founded the Northampton Freedom From Torture local supporter’s group earlier this year. Part of the reason for setting up the group was to help foster compassion towards people seeking safety in our local area. Admittedly, we’ve been pretty quiet so far (workloads, life etc. – we welcome volunteers to help organise events) but for Refugee Week we have organised a film screening of MATAR and The First Drop of Rain: Making MATAR.

MATAR is a WaterBear Original following the story of an asylum seeker in England who, when confronted with the hostile immigration system in the UK, is forced to live on the fringes of society and rely on his bike to survive.

A powerful and poignant story of resilience and perseverance, based on the lived experience of co-writer Ayman Alhussein. MATAR stars actor Ahmed Malek (The Swimmers) in the titular role, with BAFTA-nominated actor Youssef Kerkour (Home) and Elmi Rashid Elmi (The Swimmers). This docu-fiction short film is directed by BAFTA-winning Hassan Akkad and produced by Deadbeat Studios in association with Choose Love.

The event will be hosted on Wednesday 21st June 2023 from 5.30pm in the Morley Room at the University of Northampton. Tickets are free and can be booked here but we welcome donations and sponsorship for @jesjames50’s forthcoming half marathon.

In October, Jes will be running the Royal Parks Half Marathon to fundraise for Freedom From Torture. Running is one of Jes’ favourite hobbies and is enjoyed by millions across the globe as a popular pastime and fitness activity. However, running in this capacity is a privilege. For some it is forced upon them to flee harm, torture and unlawful prosecution. Freedom For Torture is a charity which is dedicated to helping, healing and protecting people who have survived torture. The half marathon is 13.1miles and has raised nearly £60million for over 1000 charity partners since 2008, and in 2023 we are aiming to contribute to this! Watch this space for more details about the upcoming fundraising activities and sponsoring Jes take on her longest run ever for survivors of torture. You can find Jes’ Just Giving page here.

Now we have the promotion out of the way, let’s talk about why compassion matters. The UK government is intent on ‘stopping the boats’, yet the policies they propose to achieve this do not include opening safe and legal routes to those seeking safety here. Instead, governments throughout much of Europe opt for deterrent measures, the results of which mean border deaths as we have seen in the tragedy off the coast of Greece this week. The omission of opening safe routes contributes to the structural violence of immigration policy and practice in Europe and means that deaths at the border are, as Shahram Khosravi argues, an acceptable consequence of border practices. There exists a gaping chasm where the compassion should be.

Meanwhile, those who do show compassion such as those volunteering to help refugees, protesters and even refugees themselves risk criminal prosecution. Sara Mardini is among a group of volunteers who faced prosecution in Greece earlier this year for a number of charges relating to their voluntary work with refugees. Although acquitted of a number of charges, some of the volunteers still face investigation for people smuggling and other offences. Meanwhile in the UK protesters are routinely arrested for protesting inhumane deportation and the Nationality and Borders Act 2022 allows maximum sentences of life imprisonment for those piloting small boats to smuggle migrants into the UK, not considering that many of these people will be refugees themselves who have paid smugglers and been forced to pilot boats, or who have agreed to pilot a boat in return for their passage. The stakes are high for acts of compassion.

As a border criminologist and activist, the refugee ‘crisis’, political, media and public responses to people seeking safety can feel overwhelming at times. It is difficult to comprehend what one person can do, yet there is power where lots of individuals stand up against injustice. Just over a year ago, I was at a protest outside an immigration removal centre on the day the first flight to Rwanda was due to take place. There were others there and at various locations around the country, and even more mobilised on social media. Campaign groups, charities and lawyers worked together to bring a court case against the UK government. While the war is ongoing, we won the battle that day and the plane was not allowed to leave.

We can all do something to spread compassion towards people seeking safety. Actions could be as simple as learning about refugees by watching a film or reading a book. It could mean sharing your thoughts in conversations and viA social media platforms. You could write to your MP and ask them to show some compassion or volunteer with a group like our Freedom From Torture local group or participate in a protest.

Maybe HE Needs Damaging: The EDI-fication of Institutional Violence

The business case for diversity initiatives, unconscious bias training, cultural sensitivity workshops, and more are some of the things that come under institutional focuses on Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, known more commonly as EDI. These are then applied to numbers of protected characteristics named in the Equality Act 2010. In addition to EDI being difficult to measure, insurgents have spoken out against it, as it seems to have taken many for fools as a phantom limb of the Anti-Racism Industrial Complex. As white people co-opt and profit from concepts and traditions of thought that Black and Brown people created and developed. For example, “identity politics” was coined in the 1970s by the Combahee River Collective to talk about their experiences of classism, lesbophobia and misogynoir. Meanwhile, the term has been co-opted by the political right in their war against equality.

As a freelancer invited into organisations to “raise awareness” on issues pertaining to racial inequality and more, I am asked to do one-time events … but never long-term interventions that shifts the scales of power and privilege. On a basic level, institutions like schools and universities can say look how much we are doing while actually not doing anything at all. Those who lose are the students and employees from historically excluded backgrounds including Black, Asian, LGBTQ+, disabled and other violently exploited groups. So, EDI then claims to want to end inequality while actually upholding it.

***

During the COVID-19 lockdowns, I read a poetry collection called Postcolonial Banter by Bradford-based spoken word poet and educator Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan. Her poem “Decentring Diversity” illustrates the issues with more Black/Brown faces in high places as somewhat being interchangable with anti-racism: “Just because they give you a seat at the table doesn’t mean they want you to speak at the table” (p81). As expected, this reaffirmed my own suspicions about the EDI agenda: simply having more Black and Brown people as managers will not solve our problems. Encouraging more Black and Brown people to inhabit these institutions to be part of the labour force, while well-intentioned, will not solve our problems when there is little want to change working conditions (i.e racism at universities).

As universities continue to exploit international students (i.e through extortionate tuition fees and precarious visas … in partnership with the Home Office), these same institutions employ EDI “initiatives” to protect these power structures. Meanwhile, Black and Brown asylum seekers drown at sea.

Having more Black and Brown faces in high places continues be a harmful tactic in EDI discourse, as we saw with their deployment in The Sewell Report. Here the UK Government – a white instituton – curated a panel of Black and Brown “experts” in their fields (but not in racism) to conduct an inquiry that told us institutional racism doesn’t exist. As the same government continues with its “anti-woke” nonchalance in its attacks on Critical Race Theory. I want to see more people that look like me in spaces I inhabit. But at what cost? As political commentator Ash Sarkar states, “I mean, this idea that all you need is brown faces in high places is just absolutely for the birds. […] That just because somebody shares some of your identity attributes, it doesn’t mean that they are going to be organising in your interests” (DDN, 2021).

Increasingly, organisations illustrate their “commitment” to Equality & Diversity by creating a diversity role within senior leadership for a Black or Brown person, only to leave this person unsupported. These staff members become tokenised and end up speaking through whiteness (as per #FloellaGate during The Coronation, and The Sewell Report). This is what happens when you project Black and Brown people into jobs within organisations, unsupported, in places that were not designed for us in the first place. Black and Brown people should certainly consider these roles if offered (and if in an emotionally healthy position to do so), but organisations need to support them. Otherwise, we are being set up to fail.

“The concept of diversity only exists if there is an assumed neutral point from which ‘others’ are ‘diverse.’ Putting aside for now the straight, male, middle-classness of that ‘neutral’ space, its dominant aspect is whiteness. Constructed by a white establishment, the idea of ‘diversity’ is neo-liberal speak. It is the new corporatized version of multiculturalism. It is about management, efficiency, box-ticking.”

Kavita Bhanot (2015)

When “diversity” is called for in organisations, it is useful to remember “diversity” is often just euphemistic language for marked difference, often Blackness and Brownness. In saying “diversity”, organisations are also telling us who institutions are designed by and who they work for. As scholar-activist Muna Abdi stated, “Diversity work is about manging the racial optics of a space. It is about bringing together people who are marked as ‘different’ into spaces that remain designed for those with power.”

In doing so, thus, some “differences” are then seen as neutral differences (i.e white; man; cisgender; ; heterosexual; neurotypical), and some are seen as Other (i.e Black; Asian; Muslim; woman; gay; neurodivergent; transgender). In giving specific groups power in a world that thrives on hierarchy and social order, historically excluded groups always lose … including racialised wo/men and people that reject all gender binaries. These groups are also some of the worse impacted by state-manufactured violence i.e how police departments treat some humans like objects to moved out of the way.

Under the “protected characteristics” named in the Equality Act 2010, in concept being victim of racism should be threaded through all of them. i.e Black women who are more likely to die in childbirth than their white counterparts. This is a very specific experience situated under “misogynoir” (Bailey, 2010), where anti-Blackness and misogyny join hands – exclusive to Black women in their position as Black women. Since 2010, the Equality Duty has largely been understood by organisations as somewhat positive:

“The general equality duty therefore requires organisations to consider how they could positively contribute to the advancement of equality and good relations. It requires equality considerations to be reflected into the design of policies and the delivery of services, including internal policies, and for these issues to be kept under review.”

Public Sector Equality Duty

Within higher education, gender equality frameworks like Athena Swann continue to privilege gender over race (Bhopal and Henderson, 2021). One must ask why? In short, some academics would say that with white experiences as the default setting (even in women’s experiences of misogyny), there is no priority for Black and Brown women to be included. So, for Black and Brown people, “progress” only tends to happen within a white supremacist system when those interests are conjoined with the goals of whiteness. In Critical Race Theory, we call this “interest convergence” (Bell, 1980). With the logic of diversity as a euphemism for Black / Brown (Bhanot, 2015), these initiatives also continue to omit the role of colour-conscious racism. This recentres white people as the “common sense” or universal worldview.

***

Often, I recieve emails from schools and others asking for EDI training; I don’t do EDI work, I do disruption work – with much of it challenging dominant power structures! EDI work in my experience has been about reform, not reparations: it has been about firefighting within institutions and managing acceptable levels of violence (i.e through resilience / “cultural sensitivity” workshops, and unconscious bias training … ugh).

In her thread about ‘unconscious bias training’, Muna Abdi also reminds us that this not something to ignore as a “tick-box exercise, it is a deliberate organisational decision and originally implemented to limit corporate risk. Furthermore, Muna tells us how it diverts attention from a needed focus on institutional and structural violence into a focus on individual violence between people.

The Equality, Diversity and Inclusion agenda has been one of the biggest traps to hit education in decades. In March, I got into a discussion with a teacher on Twitter about this. Her tweet suggested that anybody against the EDI agenda’s concepts were probematic, when in truth there is a lot wrong with EDI because it doesn’t do what it says. And in fact, in being designed around giving institutions plausible deniability and limiting corporate risk it keeps the violence going.

In late 2022, I made a complaint about a university conference. The event was situated around anti-racism in education (or so it claimed), but the event reproduced racism and whiteness in different ways. I was horrified. What struck me is how “good white people” (Sullivan, 2014) had psyologically distanced themselves from “bad supremacists.” In my complaint, it reasserted how power works and that white “anti-racists” can be some of the most racist people to challenge. As Sara Ahmed writes, “To compain at the university is to be treated as ungrateful for the benefits you have recieved from the university: the freedom to make your own interpretation, the freedom to be critical, academic freedom” (p135).

For me, EDI has been about boxticking and efficiency, using the “racial optics” of Black and Brown people for university brochures, working groups, “race equality centres” and so forth, while campus police and security continue to harrass Black students. Universities draw on the language of EDI to encourage students and staff to study/work there: “non-performativity” (Ahmed, 2018: 333). But language does not translate to transforming hostile spaces into safe ones (better yet, less hostile … in academia, safe spaces do not exist for Black and Brown staff unless we make them ourselves). Thus the brochures, and other forms of marketing are used to create the appearance without action (Ahmed and Swann, 2006).

Or as Nirmal Puwar (2004) writes,

“In policy terms, diversity has overwhelmingly come to mean the inclusion of different bodies. It is assumed that, once we have more women and racialised minorities, or other groups, represented in the hierarchies of organisations (government, civil service, judiciary, police, universities and the arts sector), especially in the élite positions of those hierarchies, then we shall have diversity. Structures and policies will become much more open when these groups enter and make a difference to organisations.”

Nirmal Puwar

Too much and often, I see organisations framing their equality ‘commitments’ as diversity strategies sidestepping the violence of patriarchy, white supremacy, ableism, and cis-heteronormativity culture. In their bums on seats approach (also centring capitalism), they fail to recognise the violence of Equality and Diversity on the people they “intend” to help. We then see term like “decolonisation” used interchangably with EDI, when in fact they are more likely opposites; EDI keeps the violence going, decolonisation roots it out – literally attacks it at the stem! Intersectionality has also been used to give EDI more credibility or kudos, of course co-opted by white institutions trying to remain relevant.

“The easy adoption of decolonizing discourse by educational advocacy and scholarship, evidenced by the increasing number of calls to “decolonize our schools,” or use “decolonizing methods,” or, “decolonize student thinking”, turns decolonization into a metaphor” (p1).

Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang

As useful as EDI may be to some, its ethos in large, conflicts with both anti-racist work and decolonisation as a practice. Frequently, EDI work within institutions avoids looking at racialisation, thus centring whiteness as sameness and avoiding systemic oppression altogether. It does the work of the corporate agenda, hence “nonperformativity” (Ahmed, 2006). In this lack of intentional work (also supported by universities), racial literacy is sidelined. The late Lani Guinier (2004) defines racial literarcy as “the capacity to decipher the durable racial grammar that structures racialized hierarchies” (p100).

The power of white supremacy illustrates that those not racialised as white are not able to bring their full authentic selves into a space. For example, in my experience at work – I am either Black or disabled – but simultaneously policed from being both. This is how whiteness maintains its power in diversity work because EDI only allows us to look at one identity position at a time. Whiteness, thus reproduces itself in spaces where it is also being interrogated (Ahmed, 2021: 158). When you question the questioning, and the thinking behind the questions, you are then placed under surveillance:

“… the [w]hite eye only, an eye that constantly has the [Black] … academic body – individual, collective, epistemological – under surveillance for any sign of trouble, any possibility of claim of racism to break the uneasy [w]hite [friendliness] of academia” (p59).

Shirley Anne Tate

Whiteness by care is still whiteness. Neoliberals would say relationships between humans are now transactional and purely economic in hope of monetary exchange. Violence by EDI is still violence. EDI keeps the violence going and is the neoliberal’s equality. It’s an empty gesture that gives institutions (like universities) plausible deniability and limits corporate risk. It is not the job of HR departments to look after employee welfare, but to limit corporate risk (i.e complaints about racism, sexual harrasssment etc etc). It just so happens the former informs the latter, and HR exists to protect reputational damage.

Indeed, EDI is full of empty promises that lumps the experiences of people whose daily lives are encompassed with being on the recieving end of extreme violence … with the same people who talk about this “journey of learning” we are all on … from a vantage point of privilege. The institutional equality agenda make me feel unsafe at work. Institutions enjoy talking up policy, but not the culture of terror that exists in the workplace. Not because of the dangerous potential of bad policymaking (though that also exists), but the dangerous potential of employees who fail upwards into unaccountable power.

“Things might appear fluid if you are going the way things are flowing. When you are not going that way, you experience the flow … [a]s a wall” – Sara Ahmed