Staff Changemaker of the Year 2022: Paula Bowles

Recently I received a nomination for a Changemaker Award, even more surprising, last night I won the Staff Changemaker of the Year Award. You can see the nomination below:

As our regular readers will now, we’ve been blogging for over five years on a variety of different and diverse topics, always with criminology at their heart. However, the pandemic changed the blog beyond recognition. Whilst our bloggers and readers were still fascinated by criminology, the worries and fears around the pandemic and lockdown, made concentration challenging for all of us. For me the turning point was David Hockney’s (2020): Do Remember They Can’t Cancel the Spring

It seemed to me that we all needed something to ease the pressure and so My Favourite Things was born. It offered every blogger the opportunity to think about things (other than the pandemic), and to reflect on what mattered to them on a personal level. Each of these entries are a snapshot of the time at which they were written and were completed by a wide range of additional reflections around the Pandemic and Me. Each of these showed the need we had for human contact, for a place to discuss, vent and escape from everyday life. The blog became a focal point for many, as illustrated by our viewing figures:

I have loved reading since childhood, it plays an important part in my mental health, my equilibrium, my identity. As I’ve noted before, my guilty pleasure lies in the crime fiction of Agatha Christie. I thought if reading works such magic for me, maybe a book club would offer space, time and companionship to other people. The only rules were the book must focus on broad elements of criminology, it needed to be fiction and no one in the club had read it before.

The first book, chosen by me, was a disastrous read, confusing narrative, one-dimensional characters and a very unlikely story. But, we took our book seriously, lots of heated discussion, particularly around whether or not it was a easy to move a dead body around (thanks to @5teveh we know that’s not possible). Lots of laughter and a complete break from everything else. After that the books became much better in content and characterisation (apart from one!).

I am not sure the above makes me a worthy winner of a Changemaker Award, but I do know that none of it was possible without my fellow readers and bloggers. So a big thank you to them and of course, our readers, without whom the blog would be a much quieter affair.

“No Police in Schools”: What Happens When Teachers Act Like Police?

As an educator, I have a conscious investment in the Education system. However, I’m also one of those people some would define as a “pracademic” (practitioner-academic) who still works within the fields he teaches about (in this context creative writing and history). Though with much of my writing having a socially scientific slant, I’m always thinking about education as a site of violence and liberation … most recently Child Q and the role of teachers possibly as police in disguise (at least in terms of thinking and culture). While I see arguments for removing police officers from schools, I wonder if that would do much … other than be a symbolic gesture. I do agree police shouldn’t be in schools, but the culture of policing is everywhere. The only thing that seperates police officers from others is the added state powers.

When Britons consider the problems with UK policing, I am uncertain if this stretches beyond the uniform to how some educators in schools and universities act like cops. Even after the Murder of Sarah Everard, there are many people who I have found struggle to contemplate that the main job of The Police is to uphold the status quo and that includes protecting property (i.e the streets) even if that means steamrolling The People from the streets (i.e protesters). Moreover, Child Q (a Black child) was brutalised by London Met in 2020 further discussed in a 2022 report while a Mixed-Race child (known under alias Olivia) was similarly brutalised in May 2022 strip-searched whilst on her period. There has since been a third victim shedding light on the extremities of London Metropolitan Police’s strip-search practices.

When I was a sabbatical officer at Northampton, I sat on a number of disciplinary panels where panel members questioned students with the same manner as a police officer. Considering these students were largely Black (in my experience) and the panellists white, these encounters always had very racist overtones. Talking to white students, the offenses Black students were punished for … white students would boast about even with staff knowing. Based on the 2011 census Black people are 3% of the population (the 2021 data will be different … whenever released). However, during my 2019-20 sabbatical year, investigated deaths after police contact were disproportionate (Andrews, 2016; IOPC, 2017/18). And while 3% of the population was Black, we also make up 13% of prisoners (Andrews, 2019: xxiii).

With many Black British students at Northampton from north and south London (where if you are Black, you are also at greater risk of being stopped by police), the fact these panel members acted like police simply adds harm revisiting the strained race relations between Black civilians and white institutions (including police, education, and healthcare). This also revisits the sociohistorical significance of the relationship between ‘white masters and enslaved Black people’ with the crimes of yesterday playing out today causing harm tomorrow. The recent Living Black report simply adds to that. And as an educator who does go into schools, I know policing does happen in classrooms whether those schools have police officers on site or not. As Carla Shalaby (2017) writes these students as:

“…the caged canaries, children who are more sensitive than their peers to the toxic environment of the classroom that limits their freedom, clips their wings, and mutes their voices.”

When I tell people (let’s be honest largely white people) that I am no fan of the Police, they often respond with individual positive experiences they have had with individual police officers as a way to silence my experience. Often along the lines of my dad’s a police officer and a good just man … how could you hate him? Silencing through “whataboutery” unwilling to acknowledge that race and policing has a British history to it that goes way back to at least the 1919 Race Riots. As historian James Walvin (1973) writes

“All neutral observers agreed that the black community was on the defensive and yet its members, in trying to defend themselves were arrested and prosecuted for their attempts at self-defence, while all but a handful of the white aggressors went unchallenged” (p207).

Generally, I need a very good reason to call the Police because I know even if you call them for help, they can turn on you (especially if you’re Black). I know if I call the Police to an incident, I am not only putting myself in danger but also every Black person in a two-mile radius in danger. Britain is not America and they do not have guns as standard issue, but we must also not pretended that violence begins and ends with guns. Yet, seemingly many white people I have spoken to seem to find it more difficult (in my experience) to consider the institution of policing and how that institution is violent and harms people (even post-George Floyd). Yes, Black people are disproportionately harmed but we must not pretend we’re alone in that. Whilst you can take police officers out of schools (and university … ahem), that ideology of discipline and control can still reside in staff when given power within spheres of influence.

The book Policing the Crisis (Hall and Colleagues, 1978) recognised a change in authoritarian measures levied against Britain’s Black communities that was largely done with public consent in the 1970s. The media took the role in narrating ‘social knowledge’ of street crime and created a mythology around the “mugger” which street crime was racialised against. Thus social anxieties around young people and “urban space” and young Black people (especially males) was viewed through. I see these social anxieties still playing out today as young Black children are policed in classrooms, not necessarily by police officers but by teachers maintaining “law and order.” This is further complicated by adultification where Black children are seen as older than they are – more “adult-like”, more “sexual”, more “mature.”

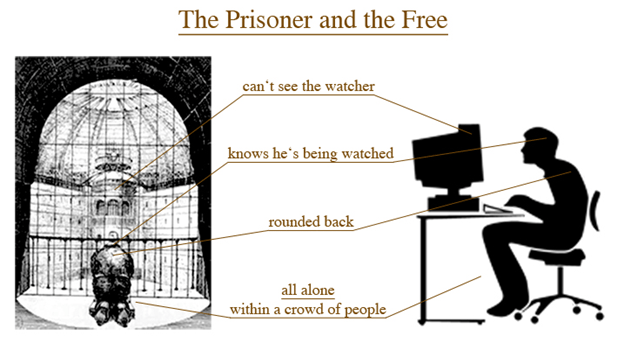

At a university level, I know this policing happens in housing and accomodation. Whilst as a sabbatical officer at Northampton between 2019-20, I spoke to Black students who had experienced racist incidents from Residential Life, and these students would not make complaints out of fear much in the same culture of Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish and Jeremy Bentham’s “panopticon.” These students knew they were being watched and policed in different ways, but they could not point at the aggressor.

As Nirmal Puwar states

“There is an undeclared white masculine body underlying the universal construction of the enlightenment ‘individual’. […] In the face of a determined effort to disavow the (male) body, critics have insisted that the ‘individual’ is embodied, and that it is the white male figure … who is actually taken as the central point of reference. […] It is against this template, one that is defined in opposition to women and non-whites — after all, these are the relational terms in which masculinity and whiteness are constituted — that women and ‘black’ people who enter these spaces are measured” (Puwar, 2004: 141).

When I was sixteen, I was one of those students that was excluded (put in internal isolation for three days for talking in class … definitely a disproportionate reaction to the misdemanour). And here, I know this experience is relatively mild in proxmity to many of my Black peers at other schools who were being punished multiple times a week (and others expelled). When many white people talk to me about school, the common denominator is that it was somewhere they felt relatively safe. Now, I get emails from Black parents of Black children and white parents of Black Mixed-Race children about racism in schools and how the schools don’t do anything. The policing of Black racialised bodies within schools is a further discussion to be had, and my community in Northamptonshire is not beyond criticism.

The frequency to which I hear Black students are punished at school and university is alarming, not surprising to see the the crossover between race and prison … as well as neurodiversity and prison where those who are seen to be “difficult” invading the space of the classroom are punished: “we have, then, a public execution and a timetable, they do not punish the same crimes nor the same type of delinquent, but they each define a certain penal style” (Foucault, 1975: 7). In this context, Foucault was talking about the man who pulled a penknife on King Louis XIV. The man was publicly drawn and quartered. He is then compared to the schedule of a prisoner in the House of Prisoners eighty years later. Two very different punishments but both ultimately damaging in different ways and products of different épistemes.

However, what I draw from this is how in today’s society, difference is punished, and there is a longevity and immediacy to the punishment. For example, the school-to-prison pipeline sees a figurative drawn-quartering of its victims that sees children through mechanisms of punishment all their lives. If they do manage to escape the prison system, that record is held over their head. Our tendency is to see medieval punishments as less humane than today’s punishment systems as if there is such thing as “progressive” violence. Yet, things like social murder (hostile environment; austerity; Cost of Living) can be compared to a slow genocide while things like the British Empire are relegated as historical relics (historical indeed?)

With the de/underfunding of the police over the last decade (Fleetwood and Lea, 2022), the greater threat sits in ideologies of control which can be picked up by anybody. Norman Fairclough (1994) argued power is “implicit within everyday social practices …. at every level in all domains of life” (p50). Philip Zimbardo’s 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment is a another example. When ordinary people were given the simultative power of prison guards, that power went to their heads. Those who volunteered to be “prisoners” were subjected to that and some were traumatised. Except in schools, they are not volunteers. We do not actually need police in schools for the simulation of policing to be carried out, as teachers and other school staff can carry this out just as academics have done in my experience at university level!

The practices of prisons “… produces subjected and practiced bodies, “docile” bodies. Discipline increases the forces of the body (in economic terms of utility) and diminishes these same forces (in political terms of obedience). In short, it dissociates power from the body; on the one hand, it turns it into an ‘aptitude’, a ‘capacity’, which it seeks to increase; on the other hand, it reverses the course of the energy, the power that might result from it, and turns it into a relation of strict subjection” (Foucault, 1975: 138)

discipline and punish: the birth of the prison

Foucault also argued that since the 1600s, practices of pushing “obedience through discipline and routine” have pervaded through other spheres “as if they tended to cover the entire social body” (Foucault, 1975: 139). The dissemination of internal / external exclusions, detentions, reprimands, housepoints, praise for 100% attendance (as if students aren’t allowed to be ill?) For students with learning differences, neurodivergent (dis)abilities, physically disabilities, as well as those with mental-ill health (and more), this is also ableism practiced through the norms of the institution.

Schools prepare students for the workforce creating drones rather than full human beings. As someone that is also autistic, I remember my teachers centralising the ideas of “fitting in” and how I did not fit in with their aesthetic of existing in the world. There sits the epistemic violence where the mainstream knowledge of socialising children with other children becomes the be all and all. The routine of conformity culture and those who do not conform are disciplined and punished in various ways, where discipline to me in school was being forced to fit in (basically ABA [autistic conversation therapy]) and thus impeded my ability to construct my own identity as someone who is not neurotypical.

Ultimately because power is not exercised exclusively through physical dominance, but cultural dominance through the stories we tell and the images that get produced. We become institutionalised by the practices we have routinely been subjected to whether that be school or the prison, thus transforming ourselves – not into the best humans we can be as humans – but as “docile bodies.” Those of us that do put in the work of unlearning what we have been conditioned into are then stigmatised. We are seen as “agitators” and “trouble” as the institution protects itself. This unlearning is not bloodless and if we are to ever have a decolonial society, we must encourage and support those who go against the grain and the norms of our institutions. Not make examples of them (Ahmed, 2018; 2021).

Refugee Week 2022

Next week (20th-26th June) is Refugee Week, coming at a moment in time days after the first deportation flight of asylum seekers to Rwanda was scheduled. Luckily the government’s best efforts were thwarted by the ECHR this time. Each year Refugee Week has a theme and this year’s focus is healing. People fleeing conflict and persecution have a lot to heal from and I am pessimistic about whether healing is possible in the UK. My own research examines the trajectories of victimisation among people seeking safety. I trace experiences of victimisation starting from the context from which people fled, during their journeys and after arrival in the UK. It is particularly disturbing as someone who researches people seeking safety that once they arrive in a place they perceived to be safe, they continue to be victimised in a number of ways. People seeking safety in the UK encounter the structurally violent asylum ‘system’ and discriminatory attitudes of swathes of the public, sections of the media and last not certainly not least, political discourse. Even after being granted leave to remain, refugees face a struggle to find accommodation, employment, convert education certificates and discrimination and hate crime is ongoing.

Over the years I have supported refugees who suffered breakdowns after having their asylum claim awarded. They are faced with the understanding of the trauma they suffered pre-migration, compounded by the asylum system and the move-on period following claims being awarded. Yet this is no time to heal. In the wake of the Nationality and Borders Act 2022, no migrant nor British citizen with a claim to citizenship elsewhere is safe. There is no safety here and therefore there can be no healing, not meaningful healing anyway.

Despite my negative outlook on the state of immigration policy in the UK, there are some positive signs of healing for some people seeking safety. These experiences are often facilitated by peer support, grassroots organisations and charities. I recall one woman who had fled Iraq coming into a charity I was undertaking research in. When we met for the first time, she was tiny and looked much older than she was. She would pull her veil tightly around her head, almost like it was protecting her. This woman did not speak a word of English and the only volunteer Kurdish Sorani interpreter did not attend the group every week. The womens’ group I attended conducted activities which overcame language barriers and at the time we were working with tiles and mosaics on a project which lasted a few weeks. During this time I could visibly see this woman start to heal. She started to stand up straight, making her appear taller. Her face softened and she appeared younger. She started smiling and her veil loosened. She was relaxing among us. In my experience, I’ve noticed that the healing comes in ebbs and flows. Relief of being ‘safe’, compounding stress of asylum, making friends, waiting, waiting, waiting for a negative decision, being supported by NGOs, letters threatening deportation, having a ‘safe’ place to live, having a firework posted through your letterbox.

For me this week is about celebrating those fleeting moments of healing, since I spend so much of my time discussing and researching the negative. The University of Northampton is co-hosting a number of events to mark Refugee Week 2022, starting with a service being held to remember all those seeking sanctuary both past and present. The event will be held on Monday 20th June at 1pm at Memorial Garden, Nunn Mills Road, Northampton, NN1 5PA (parking available at Midsummer Meadow car park).

Monday will end with an ‘in conversation with’ event with University of Northampton doctoral candidate Amir Darwish. Amir is Kurdish-Syrian and arrived in the UK as an asylum seeker in 2003. He is now an internationally published poet and writer. This event will be run in conjunction woth Northampton Town of Sanctuary and will be hosted at Delapre Abbey at 7pm. You can find further details and book tickets here.

On Wednesday the University of Northampton and Northampton Town of Sanctuary will be hosting an online seminar at 3pm with Professor Peter Hopkins, whose recent research examined the exacerbation of existing inequlaities for asylum seekers during the pandemic. I’ve just written a book chapter on this for a forthcoming volume reflecting on the unequal pandemic and it was staggering – but unsurprising – to see the impact on asylum seekers. This seminar can be accessed online here.

The week’s events will conclude with a Refugee Support Showcase which does what it says on the tin. This event will be an opportunity for organisations working with refugees in the local area to show the community the valuable work they do. This event will take place on Thursday 23rd June 4-6pm at the Guildhall, St. Giles Square, Northampton.

This year the University has worked with a number of organisations to produce a well-rounded series of events. Starting with reflection and thought of those who have sought, and continue to seek sanctuary and celebrating the achievements of someone who has lived experiences of the asylum system. Wednesday contibutes to the understanding of inequalities for people seeking safety and we end Friday on a positive note with the work of those who facilitate healing.

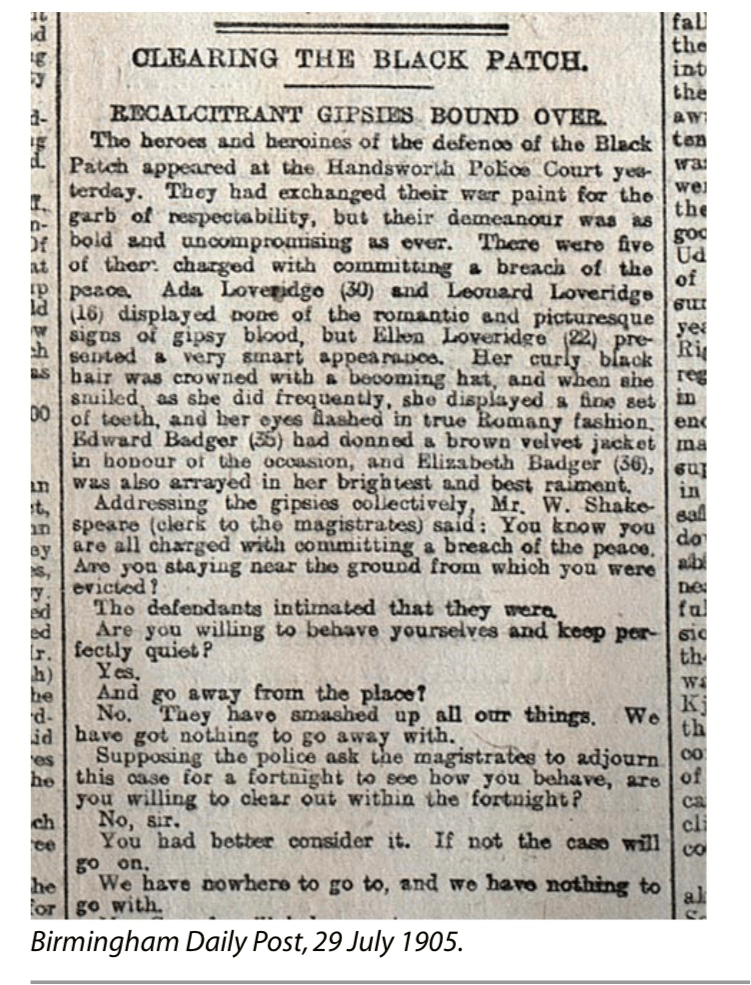

‘By order of the Peaky Blinders’: GRT History Matters

Once Gypsy Roma and Traveller (GRT) history month commences Gypsy and Traveller histories are largely ignored. This is on par with the the erasure of GRT history and contemporary culture within mainstream Britain. Given this, I was surprised that the very popular Peaky Blinders starred Birmingham based main characters and their families who appear to be Brummies, of Romany, Gypsy and Irish Traveller heritage.

In many ways representation within Peaky Blinders is problematic, it is typical that once GRT people appear as main characters their lifestyles are associated with gangs, sex and violence. But there are a lot of positives, the episodes are filled with fabulous costumes, interesting characters, plots, settings and music. There is certainly a lot of pride that comes with the representation of Birmingham based lives of mixed heritage Gypsy and Traveller families on screen.

Peaky Blinders is set in a time era which is just after WWI and appears to end in the 1930s. Whilst the series is fictional, there are many parallels that can be drawn between the lives of the fictional main character Tommy Shelby and his family and the real-life lived histories of Gypsy and Traveller people.

Peaky Blinders does well to de-mythisise the assumption that Gypsy and Traveller people do not mix with gorgers and do not participate within mainstream society. To illustrate, Tommy and his brother’s fought in WWI and experienced the damaging aftereffects of war participation. In reality, despite previously being subjected to British colonial practices and being treated with distain by the State many British Gypsy and Traveller people would have had no choice but to fight in this war due to conscription. Many would have lost their lives because of this.

Note that Tommy’s family mostly lived within housing and were working within mainstream industrial society. In reality, in industrial cities like Birmimgham many nomadic Gypsy and Traveller lifestyles would have been under threat due to land purchases made by gorgers for the purpose of building factories and housing (Green, 2009). Upon purchase of this land nomadic groups would be evicted from it, this would have left many homeless, with the increased the pressure to assimilate. This would result in work life changes, hence, Gypsy and Traveller people worked alongside gorgers in factories, where the pay and conditions would have been poor (Green, 2009).

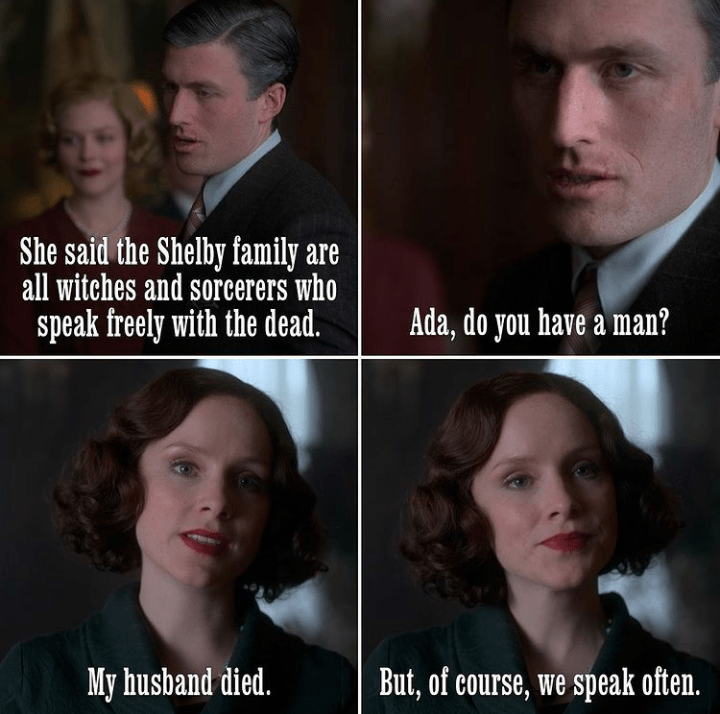

Just like prejudice in reality, even when living within housing Tommy and his family experience prejudice from within and outside of their own community. Tommy is referred to as a ‘dirty didicoi’ seemingly due to the perception of his mixed heritage and not being of ‘full-blooded’ Gypsy stock. In response to an anti-gypsy slur Tommy mocks stereotypes by stating that as well as his day job he ‘also sells pegs and tells fortunes’.

Towards the end of Peaky Blinders the promotion of fascism by elite figures is central to the storyline. Just as in reality, there was the development of the British Union of Fascists political party. Prejudice and fascist ideas contributed to categorising Gypsys as an inferior race. Whilst Peaky Blinders ends before WWII it is harrowing to know that these ideas influenced the extermination of Roma and Gypsies during the Nazi regime. Many British Gypsy and Traveller soldiers lives would have also been lost in fighting the Nazi’s in WWII due to this.

It is unfortunate that the women have less screen time in Peaky Blinders, but their personalities did shine. Ada’s character and response to prejudice is ace, whether this is responding to street hecklers, an elite eugenicist women’s ethnic cleansing ideas, or her son’s prejudice towards his sister. When her son refers to his sister as a ‘thing’ and states that she would ‘get them killed’ as she was a Black-mixed race child she responds by stating, ‘where will they send you Karl?’ whilst making him aware that he could also be subjected to persecution due to having a Jewish father and a Gypsy mother.

This year marks the end of Peaky Blinder’s episodes, the last episode is great. Tommy returns to his roots – choosing to end his days with his horse, wagon and photographs of his family. But he then wins against all the odds! Unfortunately, whilst Peaky Blinders has been celebrated there is less celebration of Gypsy and Traveller ethnicities, these were completely ignored within the documentary The Real Peaky Blinders.

Through whitewashing Gypsy and Traveller peoples histories are frequently denied. To adapt David Olusoga’s words, ‘[Gypsy and Traveller] history is British history’. An awareness of Roma Gypsy and Traveller history should not only reside with Gypsies and Travellers alone, or exist at the margins, as these are connected to all of us. As Taylor and Hinks (2021) indicate, if there is increased awareness that past and present themes of percecution this might enable increased support for Gypsy, Roma and Traveller rights – this is vital.

References:

Olusoga, D. (2016) Black and British: A forgotten History, BBC [online].

Taylor, B. and Hinks, J., (2021). What field? Where? Bringing Gypsy, Roma and Traveller History into View. Cultural and social history, 18(5), pp.629–650.

RACIST BRITAIN: Abolishing London Met is the Only Reasonable Move

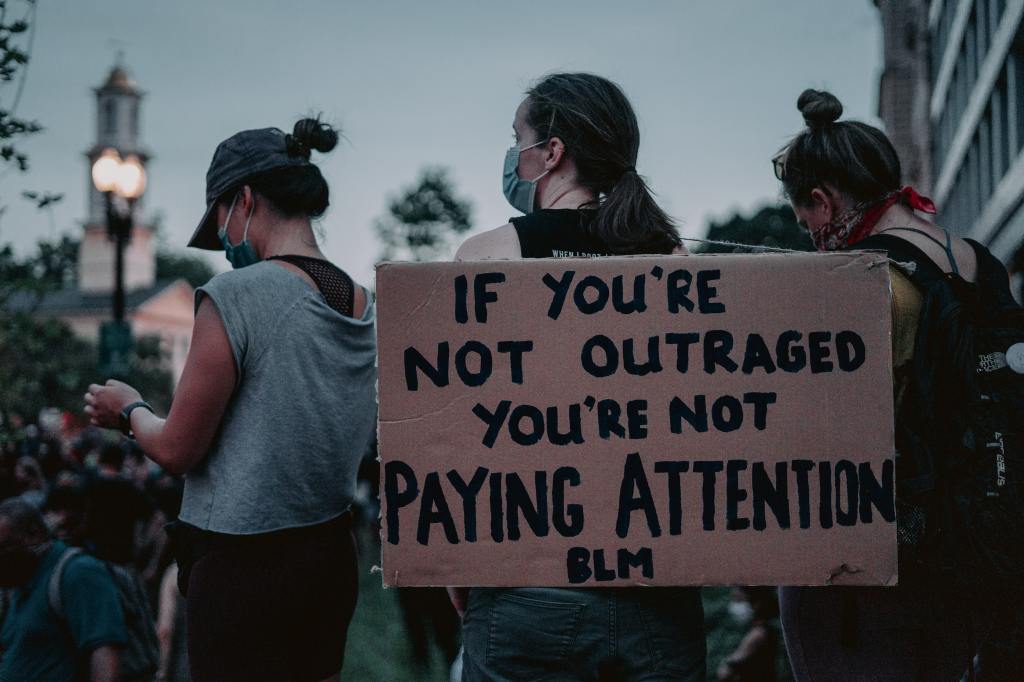

NB: While the term ‘abolition’ has often been used in reference to African Chattel Enslavement, it is also used in the context of police and prisons. i.e the work of Angela Davis has long advocated for prison abolition, while police abolition and #DefundthePolice were debated at the pique of the Black Lives Matter movement. Especially when US Congressperson Cori Bush used the slogan on her winning ticket.

In a UK context, police abolition specifically may be considered even more so, following the Murder of Sarah Everard and the two incidents of police terrorism from London Met on Black and Brown children: most infamously on Child Q and even more recently in the ordeal of an autistic Mixed-Race fourteen year-old, who like Child Q was strip-searched while menstruating on their period. A third strip-search victim has now been reported, but their race has not been stated (as of June 2022).

With consistent cuts since the arrival of the Conservatives in 2010, it could be argued British policing has been defunded for some time (Fleetwood and Lea, 2022) where in response to “Defund the Police” Kier Starmer called it “just nonsense”. Following the second anniversary of the Murder of George Floyd, I am not sure what has changed, and in some cases, we are worse off than we were in June 2020 (i.e Nationality Bill, Policing Bill, Sewell Report). However, Sarah Everard and Child Q are simply two examples in a trajectory of incidents by London Met that show the problems within policing are not only symptomatic of society, but that only defunding will not go far enough in combatting something that is also sociocultural and ideological. Simply, joining the police does not make a person racist, misogynist (etc etc), but culture and ideology via power can exasperate the biases people have within them.

Whilst in my time writing for the blog, I have scarcely touched policing, it is not a topic I am unfamilar with as I was stopped and searched for the first and only time when I was fourteen years old in an encounter which I now know could be described as “adultification” (Dancy III, 2014; Epstein and Colleages, 2017). As a Black person, this is not a topic one can just escape as many of us will have had friends and / or family members who have been negatively impacted by experiences with the Police. Teaching on Violence (CRI3003) this academic year, it radicalised me further against The Police institution pertinently with the class on the Shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes. Not just the shooting itself, but how London Metropolitan Police dealt with the aftershocks in their shoddy police work and incredibly violent mistakes.

Yet, as a Black person I am more familiar with the killings of Edson Da Costa, Rashan Charles, Joy Gardner, Sarah Reed, and even the events that lead to the Brixton Uprisings (1981). Moreover, the police terrorism at Mangrove (1970), and events surrounding uprisings in Nottingham and Notting Hill in 1958. So, this culture of overpolicing to the extent that few Black people I know have anything good to say about them, let alone London Met, has something to be said for it. Black people have long felt underprotected and you cannot train white supremacy out of an organisation who are fundamentally colonial soldiers.

The way London Metropolitan Police deal with students, protesters, women, and other marginalised groups is deplorable. Often the police skirt around their violent decision-mistaking, by describing it as “failure” but I do not believe this goes far enough. The term failure implies there were prior attempts to engage. Yet, so often they haven’t tried to engage with others, including marginalised communities (not that this is exclusive to policing). However, what appears more obvious is the lack of effort to look at themselves, as we saw when the Met claimed they didn’t see Wayne Couzens (the murderer of Sarah Everard) as one of their own even despite using his status as a police officer to kidnap and kill a woman (he was the sacrifice for patriarchy). The Met then stormed the vigil held in her memory.

Britain needs police but I am not sure we need The Police. What policing looks like needs to change, and it must be a policing that puts the most vulnerable first and asks questions why these people are vulnerable. The inquiry into the Prime Minister’s wine and cheese parties is allegedly being led by Deputy Commissioner Bas Javid (the brother of Health Secretary Sajid Javid). Defunding London Met would only go so far as to redivert resources, but the more critical questions around culture and ideology would standfast. No less than in considering the nature of gilded circles. Reform often does not change anything other than show us the problems are thousands times worse than once thought.

Last year, the 1987 murder of private investigator Daniel Morgan was revisited, and even in the 1980s London Met were considered corrupt. Abolishing the Metropolitan Police and starting anew is the only reasonable measure whether we are talking about racism, miosgyny or even out and out corruption and cronyism. However, it is not just the Met but The Police wholescale. Just as an example, South Yorkshire police have not faced repercussions from Hillsborough while West Yorkshire have not been held accountable over Jimmy Savile. The police’s problems are not in bad apples, and food scientists will tell you how one “bad apple” is enough to spoil the bunch. When we were children, how many of us had friends our parents didn’t like, and then these friends “spoilt” the dynamics of the group? After Joy Gardner, Blair Peach, Daniel Morgan, Stephen Lawrence, and others, it’s clear The Met (and Policing) is rotten to the core and that includes how it traps good and bad officers too. Systems > Individuals.

Though, we all know that when we are presented a reckoning of sorts, it will be led by establishment patsies and not the people who understand what it means to be on the recieving end of persistent institutional violence. The phrase “Abolish the Police” strikes fear into a good many people and that’s the problem. The culture of our politics has paralysed our thinking of a different world. As a population, we are so psychologically colonised by what we can see, to imagine a a different world is truly terrifying.

RACIST BRITAIN – “Skin is a Passport”: When You Are the white Shade of Asylum Seeker …

NB: In this blog the term ‘white’ will be used to describe those racialised as white within the UK as a white nation (Hage, 1998; Hunter, 2010), and those that benefit the most from white privilege. Though many Ukranian asylym seekers may in cases be racialised as white, their culture sits juxtaposed to the dominant thus ‘not white enough’, so may not always be seen as white by white British people (see what Kalwant Bhopal writes on this in the context of Gypsy Roma Travellers (2018: 29-47). Noel Ignatiev’s book How the Irish Became White may show another context in relation to Irish migration into the United States.

“Extending the gaze to whiteness enables us to observe the many shades of difference that lie within this category – that some people are ‘whiter’ than others, some are not white enough and many are inescapably cast beneath the shadow of whiteness” (Nayak, 2007).

“Skin is a passport. Epidermal citizenship” – Tao Leigh Goffe.

People tell me I spend too much time thinking and need to actually write the thing I spend so much time thinking about! However, with this blog about Ukraine, I did not want to jump on the journalistic bandwagon of being “the first” or “right”, but being thoughtful. I wanted to offer something different to mainstream consensus of “big evil Putin”, and talk about some of the discourses to race that I have been thinking about in relation to the images I have seen over the last months (much inspired by tweets, threads, and conversations lead by many Black and Brown scholars on Twitter).

Following the University’s response to the crisis, it brought me to consider how there has been more “action” than in prior crises, including Black Lives Matter and Free Palestine. For those of us descended from Black and Brown migrants who came to Britain between the 1948 Nationality Act and 1971 Immigration Act, I do not have to explain the pernicious ways British foreign policy has often tried to keep Black and Brown people out and white people in. For example, the Government’s Nationality and Borders Bill that seeks to criminalise asylum seekers, and introduce powers to revoke the citizenship of those with dual nationality (likely to impact up to six million people). When we critique the racist double standards in their response to Ukraine, white people are surprised while Black and Brown people are not.

The ease to which Britain adjusted to the cause of white Ukranians but did not and have not adjusted – to not only overseas crises in Somalia, the Yemen, and Palestine – but also at home in Europe to Black Lives Matter … is deplorable. Meanwhile numbers of Black and Brown asylum seekers are left to drown in the Channel. Seemingly, when white lives are on the line, things move! As Olena Lyubchenko writes, “Ukraine’s sovereignty and self-determination are increasingly understood by local elites to be bound up with incorporation into ‘fortress Europe’ and the making of the ‘Ukrainian nation’ as ‘white’ and ‘European.’”

The way organisations rallied around the Ukraine crisis shows when it is politically relevant to white structures and institutions, and it comes to white lives, there is a will and a way to go above and beyond what is reasonable. Meanwhile organisations that made Black Lives Matter statements in 2020 are giving lip service to anti-racism in their celebration of the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee (ahem) and gaining influence from it. Yet, equality commitments extended to Ukranian asylum seekers are not extended to Black and Brown people, both those domiciled in white nations and those migrating from areas of the Global South – where a white nation can be described as a country “… whose self-understanding, collective symbolic and affective practices, as well as material relations, are enacted through the naturalisation of whiteness via processes of external … and internal … colonisation of Black subjects” (Hunter, 2015).

If there is to be an example of ‘white solidarity’, the British response to the war in Ukraine is certainly among them. For people not racialised as white, though what’s happening in Ukraine is awful, when similar things happen to Black and Brown people, white institutions do not rush to our defense. Whether it is Somalia, the Yemen, Palestine or other Black / Brown countries, white supremacy is very much in play in whose lives are seen of worth. The treatment of Black and Brown students fleeing Ukraine at the border is also of note in the face of white supremacy and Neo-Nazism itself.

“[Ukraine] isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades. This is a relatively civilized, relatively European – I have to choose those words carefully, too – city, one where you wouldn’t expect that, or hope that it’s going to happen”.

Charlie D’Agata, cbs Senior foreign correspondent (february, 2022)

In dominant media discourse, Black and Brown people continue to be dehumanised. A pattern of constructing white Europeanness as civilised in juxtaposition to “senseless” conflicts in the Global South continue. A way of thinking that Edward Said long pointed out in his discussion of the East / West binary in Orientalism stating it as “… the corporate institution for dealing with the Orient – dealing with it by making statements about it, authorizing views of it” (Said, 1979: 3). This behaviour finds itself in ‘whiteness as ownershhip” (Harris, 1993), and through the white institution of the media making claims about the Global South “Describing it, by teaching it, settling it, ruling over it: in short Orientalism as a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient” (Said, 1979: 3).

The above quote from Charlie D’Agata as well, also revisits colonial formations of that term “white” as civilised yet at the same time othering “Black” and “Brown” as something uncivilised.

Maya Goodfellow writes:

“As they plundered, exploited and brutally controlled colonies and the people in them, all to enrich Britain as part of the growth of the capitalist project, colonialists swore by the racial hierarchy. Whiteness was not simply a descriptor; it was used to give anchor to the idea that Europe was the place of modernity and civilisation. White Europeans – in particular white upper-class men – were thought inherently modern and sophisticated; their black and brown counterparts, the opposite. The former, human; the latter, not. These ideas live on, subtly drawing a line between the developed and the developing, the advanced and the backward” (Goodfellow, 2019: 51)

The University of Northampton’s response did not really do anything, much in the same trajectory as their 2020 Black Lives Matter statement. Words lost behind inaction with no reference to Russian and Ukranian students studying at the university, nor the continuous racial trauma Black and Brown students are forced to experience. Only this time to see Black and Brown people victim yet again to ‘white terrorism’ (hooks, 1992; Yancy, 2017). For people racialised outside of whiteness, countries like Britain can be a wasteland with no escape. And this is when we are forced to create “safe spaces” seperate from the dominant.

I am not an immigrant to this country, though racialised outside of whiteness often places me as a “space invader” (Puwar, 2004) and means I can be treated like I am from somewhere else both “internally” and “externally” colonised (Hunter, 2015) in this white nation fantasy (Hage, 1998). As Black and Brown migrant bodies continue to be drowned in the seas, the 2020 Netflix film His House positions the experiences of Black asylum seekers fleeing South Sudan as pure horror. To think, the only reason people flee their countries like that and chance the seas, is if what you’re fleeing is scarier than the unknown of your destination. “Be one of the good ones” says the social worker (Matt Smith) with a wry smile.

The war in Ukraine reminds us that whiteness constitutes itself differently for those read as white, where in Britain the treatment of Gypsy Roma Traveller [GRT] people follows this pattern. Further to the treatment of Eastern Europeans such as Polish and Romanian immigrants. The legal rights of GRT people will be eroded further should the government’s Crime, Policing and Sentencing Bill reach fruition. Whiteness is as exclusively about being white as patriarchy is exclusively about being a man. It’s much more complex, but we do not get to the crux in our media culture of sound bites and simplistic answers to complex questions. Discussions about racism needs to change to extend the gaze to many shades of whiteness.

Emma Dabiri writes:

“The myth of a unified white ‘race’ makes white people, from what are in truth distinct groups, better able to identify common ground with each other and to imagine kinship and solidarity with others racialized as ‘white’, while at the same time withholding the humanity of racialized others. The ability of whiteness to create fictive kinships where differences might outweigh similarities, or where one ‘white’ group thrives and prospers through the exploitation of another ‘white’ group, all united under the rubric of whiteness constructs at the same time a zone of exclusion for racialized ‘others’, where in fact less expected affinities and even cultural resonances might reside.

In truth, this is the work of whiteness, whose invention was to serve that function. Saying that all “white” people are the same irrespective of say, culture, nationality, location, and class literally does the work of whiteness for it. But despite the continuities of whiteness – the sense of superiority that is embedded in its existence – we cannot disregard the differences that exist. This demands a truthful reckoning with the fact that the particulars of whiteness, as well as the nature of the relationship between black and white, will show up differently in different countries and require the crafting of different responses.”

From: What White People Can Do Next (2021: 45-46)

Emma Dabiri’s What White People Can Do Next (2021) follows David Roediger’s Wages of Whiteness (1991), Noel Ignatiev’s How the Irish Became White (1995), Matthew Jacobson’s Whiteness of a Different Color (1998) and Nell Irvin Painter’s The History of White People (2010), all of which in some way show how different white groups have modifiers attached when talking about “white people.” This must be discussed interlocking with other factors including culture, place/geography, and class. Through Roediger, Ignatiev, Jacobson, Painter, Dabiri, and other scholars, we can see how whiteness splits and mutates to serve its purpose of divide and rule, and really how white supremacy may also negatively impact against those read as white and ‘not white enough’ in different ways.

Social discourses to Palestine and Black Lives Matter are two examples of Black and Brown lives being beyond the interest of white institutions, while Ukraine reminds us in spite of their reality, white lives matter more. In 1985, co-founder of Critical Race Theory Derrick Bell coined a term called ‘interest convergence’ to describe the way US civil rights only became a priority when it met the “interests” of white people. Ukraine in much the same way is a declaration of white solidarity, where under white supremacy whiteness will always protect itself over the interests of those racialised outside of it.

For as long as the invention of race has ‘existed’, the protection of white interests (ownership – see Cheryl Harris) has always trumped the protection of Black and Brown lives. Ukraine aside, to think the police are there to protect you is a mark of privilege when it is the job of the police to uphold the status quo which implicates upholding white supremacy. Black and Brown students at the border were just “objects” to be moved out of the way, no different to how Black and Brown students are seen and treated on the streets in the Global North including at school and university campuses.

Nirmal Puwar writes

“There is an undeclared white masculine body underlying the universal construction of the enlightenment ‘individual’. Critics of the universal ideal human type in Western thought elaborate on the exclusionary somebody in the nobody of political theory that proclaims to include everybody. In the face of a determined effort to disavow the (male) body, critics have insisted that the ‘individual’ is embodied, and that it is the white male figure, of a changing habitus, who is actually taken as the central point of reference. The successive unveiling of the disembodied human ‘individual’ by class theorists, feminists and race theorists has collectively revealed the corporeal specificity of the absolute human type. It is against this template, one that is defined in opposition to women and non-whites – after all, these are the relational terms in which masculinity and whiteness are constituted – that women and ‘black’ people who enter these spaces are measured” (Puwar, 2004: 141).

The constructing of ‘white’ as neutral is central to white supremacy and this is also what makes Diversity and Inclusion such a problem (Bhanot, 2015). However, the Ukraine crisis further shows how whiteness can come with qualifiers and that white supremacy will use those seen as ‘less white’ to discriminate against those (overtly … schema-wise) marked outside of that ‘white’ category. Tao Leigh Goffe tweeted “Skin is a passport. Epidermal citizenship”, in my opinion to act as a double meaning. Firstly, that skin is a literal passport and can grant citizenship through various levels of “white-skin privilege” (Allen and Ignatiev, 1967; McIntosh, 1988; Kyla Lacey, 2017; Eddo-Lodge, 2017; Bhopal and Henderson, 2021).

However, there could be a further meaning to mean a passport through spaces coded as white, and citizenship in certain spaces that Black and Brown people would not be granted entry to. So, our discussions around whiteness must extend to how it appears through various social markers including class, gender, culture, political affiliation and more. If the Ukraine crisis is to be our conduit, it shows our conversations and knowledge-building around whiteness must extend from what one scholar names as “the more fasionable white privilege” into a more critical conversation about white supremacy (Mills, 2004: 31) where whiteness can work like a virus – mutating, splitting, growing, reproducing, adapting, multiplying (Seshadri-Crooks, 2000; Chow, 2002; Wiegman, 2012).

We have work to do!

RACIST BRITAIN – ‘Uncommon Wealth’: Colonialism in the Present Tense

The main title for this piece comes from a book of the same namesake by Kojo Koram.

Plantations and pub gardens; afternoon tea, cakes, caps, graduation gowns and colonial statues; white supremacist symbols upon symbols. An (in)visible web of arcane history blurring the lines between chants for anti-racism in schools and schools of white thought celebrating the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee and the ‘Best of British’. No politician, no lawyer, no academic could keep up with such walking contradictions, even the Tories and their wine and cheese soirées or a university vice chancellor mired in scandal! These entanglements even make the Prime Minister look modest.

Who wants consistency in anti-racist commitments when you can have fantasy? Who wants to talk of motifs to enslavers when you can munch on crumpets? Who wants punishment collars when there’s a national holiday and a pint in the sunshine? Pull away the veil and what are we left with? A country that boasts about multiculturalism and anti-racism in one breath, and the seemingly unconnected Platinum Jubilee in the next. Tell a story with the bite of Ozymindias, and even the most staunch anti-racists will be sitting down for a nice sherry come the Jubilee. What these narratives do, is “spectacularise” individuals and that is the power of storytelling. It turns human beings into gods and this is mass media marketing to the very extreme. Her name is Elizabeth Queen of Queens, look upon this mighty charade and despair.

Following anti-colonial resistance in the Caribbean to royal visits, current Jubilee celebrations on the British side of the Atlantic appear insensitive (these visits are simply a catalyst, not an exclusive … they were always problematic). However, as I wonder the Northampton streets I grew up on, admiration for The Crown does not seem to waiver amid local and chain businesses, seemingly having learned nothing from the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. The same institutions who posted solidarity statements that summer … colonisations of the mind remains ever-present (wa Thiong’o, 1986) in Northampton’s pubs, shops, theatres, and other institutions. While the Queen’s neck grows crooked under stolen loot, hypocrites swarm to the announcement of a national holiday. What short memories human beings have.

During a pandemic that has had a devastating impact on business (especially independent businesses), one cannot blame them taking every chance they get to recuperate losses. Yet, to do so with empire and colonialism still kicking is just not cricket. Neoliberalism, better known as neoliberal capitalism trumps all with a back-handed flag-waving jingoistic holiday while more activists will run to Buckingham Palace this summer when they get called for their gong. Arising … superficially validated by the same empire project that sustains “equal access to unjust systems” (Manzoor-Khan, 2019: 81). They need a gong over the head! I can feel this to be another long summer, full of actions that undermine pushes for lasting change. Admittedly, I am not beyond critique, but claiming to be anti-racist while peddling support for the Queen’s Jubilee is the baseline for what not to do.

Seeing numbers of organisations and people who were posting black squares and the like that summer in 2020, to now be celebrating the Jubilee, clearly their commitment was temporary.

With civil unrest in the Caribbean and anti-racism debates on this side of the Atlantic still growing strong, the level of cognitive dissonance must be astronomical to peddle anti-racism while celebrating the Queen’s Jubilee. It appears many people and their dogs have jumped on the imperial carriage to celebrate someone whose very existence undermines the best of Britain. In the same year the Colston Four were acquitted by a public jury for dispatching the Bristolian enslaver into the river, we celebrate someone in much the same symbol of pillage and plunder. Deplorable does not begin to describe it.

While I see people saying that the Queen did not benefit from colonialism in her lifetime, I remind you colonialism isn’t over. Moreover, historic events like the Mau Mau Uprisings (1952-1960) and the Suez Crisis (1956) are well within her reign, further to violent fights for independence within Caribbean Black Power movements. The British Monarchy is a constitutional monarchy, so the Queen has little power as an individual, yet the institution is no less violent than policing, prisons, the Church and others. For all Britain’s flag-waving, we know very little British history. While I do not claim to know all, I remain curious. Though, curiosity to see what lurks in the closet many would rather not know. As I frequent my favourite local venues, my spirit weeps at the sight of union jacks and St George’s flags (a symbol of violence I associate with racism and white supremacy).

The red and white … amid this nationalist fever in the regalia of Brexit, it is a reminder I am unwelcome in the country I have always called home. The acceptance of racist symbols is common in our mainstream, but worse when you see it condoned by your friends. While popularised by Lord Macpherson in the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, the term institutional racism in practice goes back centuries. Queen Elizabeth I introduced the Royal Proclomation in 1603 which could be cited as the second act of institutionalised racism on British soil, demanding “Blackamores” be expelled from her kingdom (Fryer, 1984: 12). This was precedented by the 1193 expulsion of the Jews, where Simon DeMontfort (from whom the DeMontfort University gets its name) expelled the Jews from Leicester City (DeMontfort Students’ Union, 2021).

Every monarch from Elizabeth I to George III subsequently gave their blessing to the human trafficking of Black Africans (Hirsch, 2017: 51), thus before British independent traders broke into enslavement the original beneficiaries were the monarchy. As the ‘royal’ in Royal African Company for example, is more than an honorific, but a namesake. The late Tudors and early Stuarts were up to their necks in the blood of Black people (Olusoga, 2017: 22), as were the Georgians and Victorians. Furthermore, the wealth of the monarchy we see now was largely necessitated by colonial ambition. Heck, Victoria was donned Empress of India and Elizabeth I granted the royal charter to the East India Company (Sanghera, 2021: 12).

In his 1916 book Why Men Fight, Bertrand Russell writes how “All our institutions have their historic basis in Authority.” The Crown sits among them, like bloodsucking parasites who gained most of their wealth from stealing from others including the Global South. Yet, Scotland and Wales and Ireland also have their own reasons to dislike the Crown, including the history of the Prince of Wales title which I talked about in an earlier blog (and were still up in the Caribbean doing their colonial nonsense). You have to hand it to the British state, they have perfected the art of brainwashing … convincing large swathes of the oppressed to support the monarchy while also getting the working-class to vote Conservative.

However, with the Platinum Jubilee looming I am disgusted to see numbers of organisations who were posturing Black Lives Matter statements and black squares in the long summer of 2020 now bootlicking the empire itself. It is a reminder to me that within the British Isles that there is still very little public knowledge on the history of The Crown, both as the original colonisers but also as wielders of violence against working-class communities. Those who perfected social murder. Performance and vanity.

For example, after the Murder of George Floyd in June 2020 the University of Northampton posted a BLM statement (nonetheless weak). This statement came from pressure via Twitter (after eleven days of silence, the University posted a statement). This also came with a blog entry, as it was my last as a sabbatical officer. Now, they are holding events in the image of whiteness, colonialism, and racism for the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee celebrations. This sits adjacent to UON’s “efforts” to decolonise the university (recolonise may be a more fitting term). Concurrently, the University held a week-long thread of events about the climate emergency in November 2021 which was a study in whitewashing fitting under the wider banner of whitewashing COP26. And in April 2022, they were voted among the top 25 universities for tackling inequalities in spite of repeated strike action from staff since 2021 over fair pay, pensions, and race / gender pay gaps as part of UCU industrial action nationwide. Make this make sense!!

As someone that was very active that summer and has been since, I have been tested lately thinking about the many people that claim to be anti-oppression while also supporting the Queen and thus, the institution of the monarchy. Discrimination against Harry and Meghan is also of note amid the Royal Family itself, as well as from British media. If you’re a monarchist by all means stand by your beliefs, but don’t try to be so while claiming to be anti-oppression. Worse, as Prishita Maheshwari-Aplin wrote about UK Honours: “when those who have made their names from challenging the lingering evils of the empire jump at the chance of being superficially validated by it, the hypocrisy is extremely grating.”

For a university to pontificate about its place on a list of twenty-five universities for tackling inequality, while numbers of staff are on strike during a cost of living crisis … that’s Priti Patel levels of evil. Who were the judges, Dr Strangelove and Darth Vader?

So, if you consider yourself remotely pro-human rights, I would consider thinking about your stance on the monarchy … some of the biggest hoarders of wealth and the epitome of whiteness as ownership (Harris, 1993). The pulling down of Edward Colston; the National Trust audit into stately homes and their links to enslavement and colonialism; anti-colonial uprisings in the Caribbean; the Windrush Scandal and decolonising education are all entangled in this web amid the Jubilee’s nationalist (colonialist white supremacist) fever. Whilst it may be considered British to support the Queen, it is just as British to dissent.

The fight against capitalism certainly includes ‘wealth-hoarders’ pertinently inherited wealth (and those who got it through dubious means). To be anti-racist, we must also be anti-capitalist which fundamentally underpins many intersectional movements. For example, anti-capitalism is vital to disability justice, the class struggle, and LGBT+ rights. And while everyday folks have hopped on to this jubilee band-carriage, I would really question if we should. Abolishing the monarchy is just the starting the point.