As we reach the 180th anniversary of the emancipation for when the last slave was truly free in the British Empire, we must look at the legacy of the Slave Trade today. It can be seen in the names of many Black Britons from Caribbean backgrounds. Griffiths (Welsh) and Ventour (British-French), you cannot get more European than that. My names are proof that Britain and France took part in the oppression of my ancestors. They are part of my family history. And as Glasgow Councillor Graham Campbell says, “When you are part of the crime scene, you cannot let the evidence walk away.”

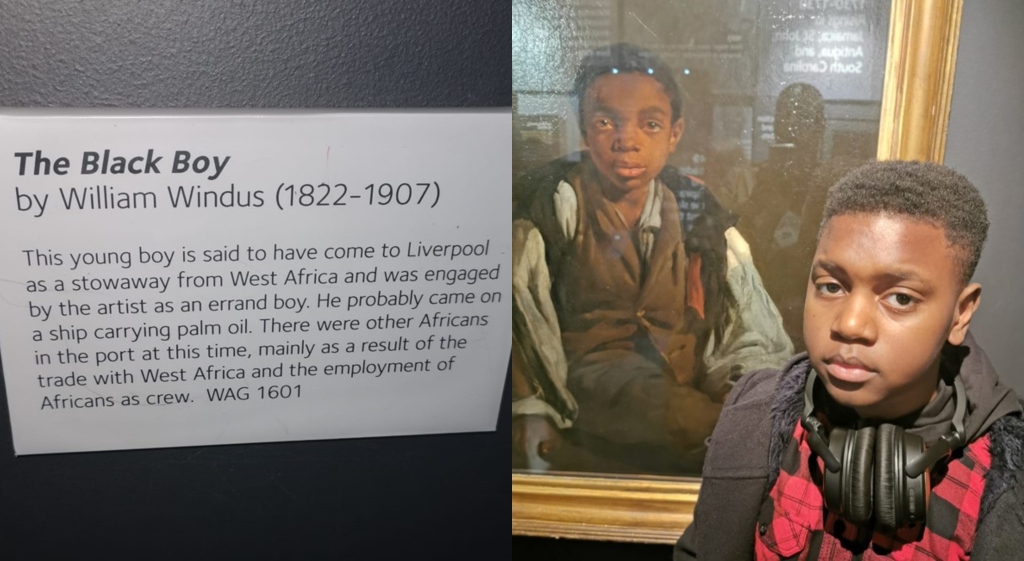

My brother’s visit to the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool with my mother brings it home. That in going there, for him it was slavery in black and white, literally. It showed that slavery didn’t discriminate by age. It impacted people from babies in their mother’s arms up to the elderly. I watched Roots for the first time at eight years old. And I will never forget Kunta Kinte saying his name. Desperately clinging on to the last piece of himself. His name. Not the name of the slave master. His African name.

In my exploration of my own names and their links with transatlantic slavery, I have seen I am the worst kind of person. When I ask a person I know to be Black British with a European-sounding last name about their names, what I’m doing is fishing on how they got that name. The fact that I know Black Britons whose last names are things like Richards, Smith or Francis. That on a CV, you would not know the colour of their skin based on their name. Speaking to many Black Britons, I find our slave-ridden past to be an uncomfortable topic, but it’s also a story that the White establishment in Britain would prefer to keep invisible out of the way.

The other day before Britain went into lockdown, I went to afternoon tea with some colleagues of mine from University. Being Black in those settings is strange in my opinion – an everyday thing that comes from colonial times, reminding me of big houses and slave plantations, and escapees would have their legs and feet amputated like Kunta Kinte. It reminds me of famine in Ireland and India, and the genocide of Indigenous Americans.

That when my ancestors were working under masters’ wrath, Master Ventour and Master Griffiths would be indulging in tea and cakes. In Britain we present colonialism as something to be proud of. That we went to these places as explorers and “civilised” the indigenous people, passing it off today as teaching them about English niceties, etiquette and table manners.

In my role at university, whenever I have encountered international students, I do my utmost to try to inform them of the history this country does not tell in its travel guides. That if they went on a tour of Trafalgar Square they would not learn that Admiral Nelson married a plantocrat’s daughter on a Nevitian slave plantation. That as part of the Royal Navy, it was his job to protect British commerce, including slave ships. We do not tell this history to holidaymakers or students in any real depth because it shows that our good etiquette and table manners are written in blood.

When I broach these subjects, I see people that just want this Black person to go back to whatever “shithole nation” he came from. Growing up, I was often silenced by my peers at school for talking about slavery. However, if you tried to silence the Jews for talking about The Holocaust or the Irish for talking about the Potato Famine, I am certain they would have something to say. For Black people, the Slave Trade is our Auschwitz and those sugar, tobacco and cotton plantations in the US and Caribbean were death camps.

Whilst there are more positive images of Black history we need to see, we cannot neglect the over two hundred years of British slavery. And if you walk around this country with its grandeur and National Trust stately homes, you will see the money of colonialism without the blood.

So, when you have the Windrush, along with their children and grandchildren living in the centre of colonial power, you are part of the crime scene and you can’t just walk away.

Awesome So many wonderful turns of phrases here. Insightful, too. It makes whitewashing history sound so insidious!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading, Diepiriye. “Whitewashing” is such a pleasant turn-of-phrase. It sounds so nice even though it’s not. And its underlying implications are violent and as you say, insidious. Language is funny that way. That even when it’s our history being erased, the term “whitewashing” decentres us from the narrative as “white”(washing) is at the centre. It’s still about White people and whiteness, even when it’s not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really liked your article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

LikeLike